Engineering

Engineering

Designing Resilient Systems Beyond Retries (Part 2): Bulkheading, Load Balancing, and Fallbacks

This post is the second of a three-part series on going beyond retries to improve system resiliency. We’ve previously discussed about rate-limiting as a strategy to improve resiliency. In this article, we will cover these techniques: bulkheading, load balancing, and fallbacks.

Introducing Bulkheading (Isolation)

Bulkheading is a fundamental pattern which underpins many other resiliency techniques, especially where microservices are concerned, so it’s worth introducing first. The term actually comes from an ancient technique in ship building, where a ship’s hull would be partitioned into several watertight compartments. If one of the compartments has a leak, then the water fills just that compartment and is contained, rather than flooding the entire ship. We can apply this principle to software applications and microservices: by isolating failures to individual components, we can prevent a single failure from cascading and bringing down the entire system.

Bulkheads also help to prevent single points of failure, by reducing the impact of any failures so services can maintain some level of service.

Level of Bulkheads

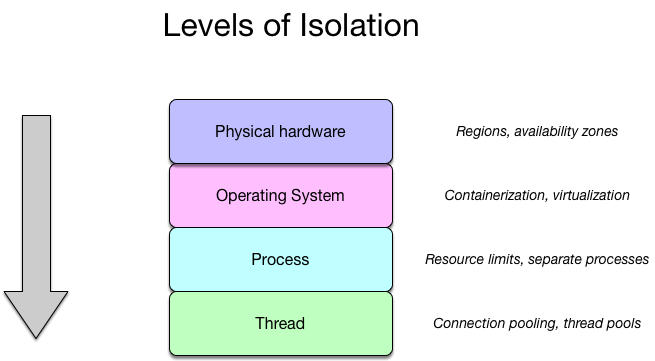

It is important to note that bulkheads can be applied at multiple levels in software architecture. The two highest levels of bulkheads are at the infrastructure level, and the first is hardware isolation. In a cloud environment, this usually means isolating regions or availability zones. The second is isolating the operating system, which has become a widespread technique with the popularity of virtual machines and now containerisation. Previously, it was common for multiple applications to run on a single (very powerful) dedicated server. Unfortunately, this meant that a rogue application could wreak havoc on the entire system in a number of ways, from filling the disk with logs to consuming memory or other resources.

Isolation can be achieved by applying bulkheading at multiple levels

Isolation can be achieved by applying bulkheading at multiple levels

This article focuses on resiliency from the application perspective, so below the system level is process-level isolation. In practical terms, this isolation prevents an application crash from affecting multiple system components. By moving those components into separate processes (or microservices), certain classes of application-level failures are prevented from causing cascading failure.

At the lowest level, and perhaps the most common form of bulkheading to software engineers, are the concepts of connection pooling and thread pools. While these techniques are commonly employed for performance reasons (reusing resources is cheaper than acquiring new ones), they also help to put a finite limit on the number of connections or concurrent threads that an operation is allowed to consume. This ensures that if the load of a particular operation suddenly increases unexpectedly (such as due to external load or downstream latency), the impact is contained to only a partial failure.

Bulkheading Support in the Hystrix Library

The Hystrix library for Go supports a form of bulkheading through its MaxConcurrentRequests parameter. This is conveniently tied to the circuit name, meaning that different levels of isolation can be achieved by choosing an appropriate circuit name. A good rule of thumb is to use a different circuit name for each operation or API call. This ensures that if just one particular endpoint of a remote service is failing, the other circuits are still free to be used for the remaining healthy endpoints, achieving failure isolation.

Load Balancing

Global rate-limiting with a central server

Global rate-limiting with a central server

Load balancing is where network traffic from a client may be served by one of many backend servers. You can think of load balancers as traffic cops who distribute traffic on the road to prevent congestion and overload. Assuming the traffic is distributed evenly on the network, this effectively increases the computing power of the backend. Adding capacity like this is a common way to handle an increase in load from the clients, such as when a website becomes more popular.

Almost always, load balancers provide high availability for the application. When there is just a single backend server, this server is a ‘single point of failure’, because if it is ever unavailable, there are no servers remaining to serve the clients. However, if there is a pool of backend servers behind a load balancer, the impact is reduced. If there are 4 backend servers and only 1 is unavailable, evenly distributed requests would only fail 25% of the time instead of 100%. This is already an improvement, but modern load balancers are more sophisticated.

Usually, load balancers will include some form of a health check. This is a mechanism that monitors whether servers in the pool are ‘healthy’, ie. able to serve requests. The implementations for the health check vary, but this can be an active check such as sending ‘pings’, or passive monitoring of responses and removing the failing backend server instances.

As with rate-limiting, there are many strategies for load balancing to consider.

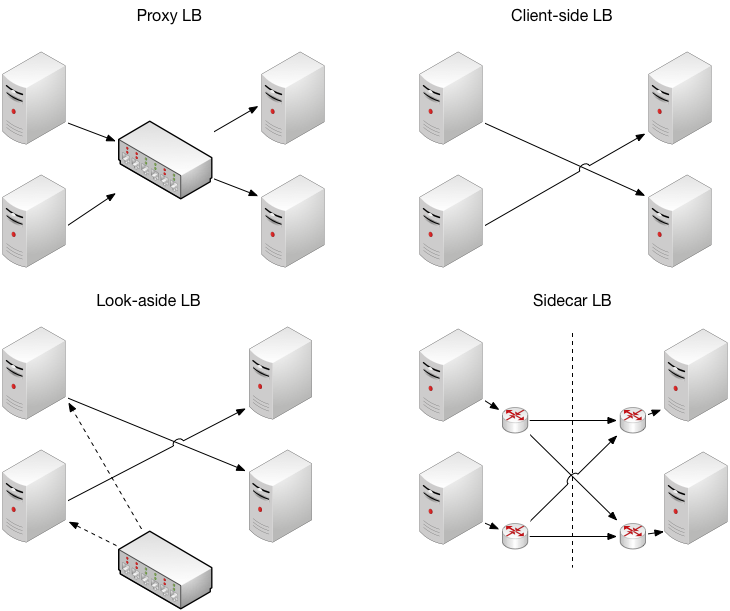

There are four main types of load balancer to choose from, each with their own pros and cons:

- Proxy. This is perhaps the most well-known form of load-balancer, and is the method used by Amazon’s Elastic Load Balancer. The proxy sits on the boundary between the backend servers and the public clients, and therefore also doubles as a security layer: the clients do not know about or have direct access to the backend servers. The proxy will handle all the logic for load balancing and health checking. It is a very convenient and popular approach because it requires no special integration with the client or server code. They also typically perform ‘SSL termination’, decrypting incoming HTTPS traffic and using HTTP to communicate with the backend servers.

- Client-side. This is where the client performs all of the load-balancing itself, often using a dedicated library built for the purpose. Compared with the proxy, it is more performant because it avoids an extra network ‘hop.’ However, there is a significant cost in developing and maintaining the code, which is necessarily complex and any bugs have serious consequences.

- Lookaside. This is a hybrid approach where the majority of the load-balancing logic is handled by a dedicated service, but it does not proxy; the client still makes direct connections to the backend. This reduces the burden of the client-side library but maintains high performance, however the load-balancing service becomes another potential point of failure.

- Service mesh with sidecar. A service mesh is an all-in-one solution for service communication, with many popular open-source products available. They usually include a sidecar, which is a proxy that sits on the same server as the application to route network traffic. Like the traditional proxy load balancer, this handles many concerns of load-balancing for free. However, there is still an extra network hop, and there can be a significant development cost to integrate with existing systems for logging, reporting and so on, so this must be weighed against building a client-side solution in-house.

Comparison of load-balancer architectures

Comparison of load-balancer architectures

Grab’s Load-balancing Implementation

At Grab, we have built our own internal client-side solution called CSDP, which uses the distributed key-value store etcd as its backend store.

Fallbacks

There are scenarios when simply retrying a failed API call doesn’t work. If the remote server is completely down or only returning errors, no amount of retries are going to help; the failure is unrecoverable. When recovery isn’t an option, mitigation is an alternative. This is related to the concept of graceful degradation: sometimes it is preferable to return a less optimal response than fail completely, especially for user-facing applications where user experience is important.

One such mitigation strategy is fallbacks. This is a broad topic with many different sub-strategies, but here are a few of the most common:

Fail Silently

Starting with the easiest to implement, one basic fallback strategy is fail silently. This means returning an empty or null response when an error is encountered, as if the call had succeeded. If the data being requested is not critical functionality then this can be considered: missing part of a UI is less noticeable than an error page! For example, UI bubbles showing unread notifications are a common feature. But if the service providing the notifications is failing and the bubble shows 0 instead of N notifications, the user’s experience is unlikely to be significantly affected.

Local Computation

A second fallback strategy when a downstream dependency is failing could be to compute the value locally instead. This could mean either returning a default (static) value, or using a simple formula to compute the response. For example, a marketplace application might have a service to calculate shipping costs. If it is unavailable, then using a default price might be acceptable. Or even $0 - users are unlikely to complain about errors that benefit them, and it’s better than losing business!

Cached Values

Similarly, cached values are often used as fallbacks. If the service isn’t available to calculate the most up to date value, returning a stale response might be better than returning nothing. If an application is already caching the value with a short expiration to optimise performance, it can be reused as a fallback cache by setting two expiration times: one for normal circumstances, and another when the service providing the response has failed.

Backup Service

Finally, if the response is too complex to compute locally or if major functionality of the application is required to have a fallback, then an entirely new service can act as a fallback; a backup service. Such a service is a big investment, so to make it worthwhile some trade-offs must be accepted. The backup service should be considerably simpler than the service it is intended to replace; if it is too complex then it will require constant testing and maintenance, not to mention documentation and training to make sure it is well understood within the engineering team. Also, a complex system is more likely to fail when activated. Usually such systems will have very few or no dependencies, and certainly should not depend on any parts of the original system, since they could have failed, rendering the backup system useless.

Grab’s Fallback Implementation

At Grab, we make use of various fallback strategies in our services. For example, our microservice framework Grab-Kit has built-in support for returning cached values when a downstream service is unresponsive. We’ve even built a backup service to replicate our core functionality, so we can continue to serve consumers despite severe technical difficulties!

Up Next, Architecture Patterns and Chaos Engineering…

We’ve covered various techniques in designing reliable and resilient systems in the previous articles. I hope you found them useful. Comments are always welcome.

In our next post, we will look at ways to prevent and reduce failures through architecture patterns and testing.

Please stay tuned!