Engineering

Engineering

Orchestrating Chaos Using Grab's Experimentation Platform

Background

To everyday users, Grab is an app to book a ride, order food, or make a payment. To engineers, Grab is a distributed system of many services that interact via remote procedure call (RPC), sometimes called a microservice architecture. Hundreds of Grab services run on thousands of machines with engineers making changes every day. In such a complex setup, things can always go wrong. Fortunately, many of the Grab app’s internal services are not critical for user actions like booking a car. For example, bookmarks that recall the user’s previous destination add user value, but if they don’t work, the user should still enjoy a reasonable user experience.

Partial availability of services is not without risk. Engineers must have an alternative plan if something goes wrong when making RPC calls against non-critical services. If the contingency strategy is not implemented correctly, non-critical service problems can lead to an outage.

So how do we make sure that Grab users can complete critical functions, such as booking a taxi, even when non-critical services fail? The answer is Chaos Engineering.

At Grab, we practice chaos engineering by intentionally introducing failures in a service or component in the overall business flow. But the failed’ service is not the experiment’s focus. We’re interested in testing the services dependent on that failed service.

Ideally, the dependent services should be resilient and the overall flow should continue working. For example, the booking flow should work even if failures are put in the driver location service. We test whether retries and exponential fallbacks are configured correctly, if the circuit breaker configs are set properly, etc.

To induce chaos into our systems, we combined the power of our Experimentation Platform (ExP) and Grab-Kit.

Chaos ExP injects failures into traffic-serving server middleware (gRPC or HTTP servers). If the system behaves as expected, you can be confident that services will degrade gracefully when non-critical services fail.

Chaos ExP simulates different types of chaos, such as latencies and memory leaks within Grab’s infrastructure. This ensures individual components return something even when system dependencies aren’t responding or respond with unusually high latency. It ensures our resilience to instance failures, as threats to availability can come from microservice level disruptions.

Setting Up for Chaos

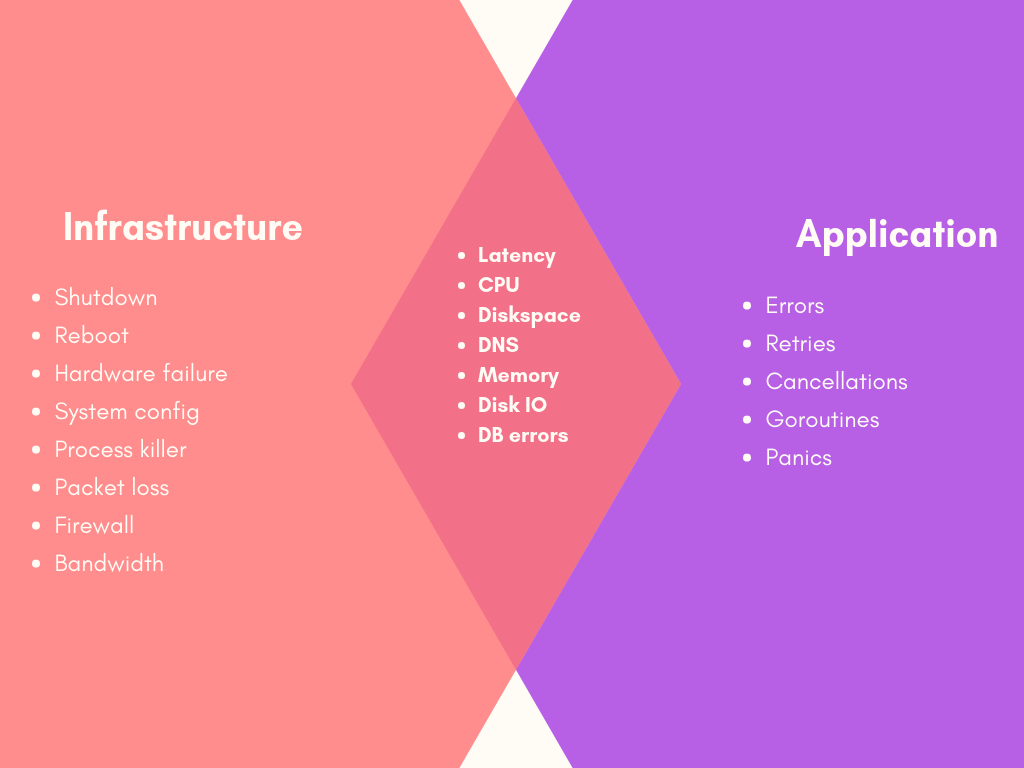

To build our chaos engineering system, we identified the two main areas for inducing chaos:

-

Infrastructure: By randomly shutting down instances and other infrastructure parts

-

Application: By introducing failures during runtime at a granular level (e.g. endpoint/request level)

You then enable chaos randomly or intentionally via experiments:

-

Randomly

-

More suitable for ‘disposable’ infrastructure (e.g. ec2 instances)

-

Tests redundant infrastructure for impact on end-users

-

Used when impact is well-understood

-

-

Experiments

-

Accurately measure impact

-

Control over experimental parameters

-

Can limit impact on end-users

-

Suitable for complex failures (e.g. latency) when impact is not well understood

-

Finally, you can categorise failure modes as follows:

-

Resource: CPU, memory, IO, disk

-

Network: Blackhole, latency, packet loss, DNS

-

State: Shutdown, time, process killer

Many of these modes can be applied or simulated at the infrastructure or app level, as shown:

For Grab, it was important to comprehensively test application-level chaos and carefully measure the impact. We decided to leverage an existing experimentation platform to orchestrate application-level chaos around the system, shown in the purple box, by injecting it in the underlying middleware such as Grab-Kit.

Why Use the Experimentation Platform?

There are several chaos engineering tools. However, using them often requires an advanced level of infrastructure and operational skill, the ability to design and execute experiments, and resources to manually orchestrate the failure scenarios in a controlled manner. Chaos engineering is not as simple as breaking things in production.

Think of chaos engineering as a controlled experiment. Our ExP SDK provides resilient and asynchronous tracking. Thus, we can potentially attribute business metrics to chaos failures directly. For example, by running a chaos failure that introduces 10 second latencies in a booking service, we can determine how many rides were negatively affected and how much money was lost.

Using ExP as a chaos engineering tool means we can customise it based on the application or environment’s exact needs so that it deeply integrates with other environments like the monitoring and development pipelines.

There’s a security benefit as well. With ExP, all connections stay within our internal network, giving us control over the attack surface area. Everything can be kept on-premise, with no reliance on the outside world. This also potentially makes it easier to monitor and control traffic.

Chaos failures can be run ad-hoc, programmatically, or scheduled. You can also schedule them to execute on certain days and within a specified time window. You can also set the maximum number of failures and customise them (e.g. number of MBs to leak, seconds to wait).

ExP’s core value proposition is allowing engineers to initiate, control, and observe how a system behaves under various failure conditions. ExP also provides a comprehensive set of failure primitives for designing experiments and observing what happens when issues occur within a complex distributed system. Also, by integrating ExP with chaos testing, we did not require any modifications to a deployment pipeline or networking infrastructure. Thus the combination can be utilised more easily for a range of infrastructure and deployment paradigms.

How We Built the Chaos SDK and UI

To build the chaos engineering SDK, we leveraged a property of our existing ExP SDK - single-digit microsecond-level variable resolution, which does not require a network call. You can read more about ExP SDK’s implementation here. This let us build two things:

-

A smaller chaos SDK on top of ExP SDK. We’ve integrated this directly in our existing middleware, such as Grab-Kit and DB layers.

-

A dedicated web-based UI for creating chaos experiments

Thanks to our Grab-Kit integration, Grab engineers don’t actually need to use the Chaos SDK directly. When Grab-Kit serves an incoming request, it first checks with the ExP SDK. If the request “should fail”, it applies the appropriate failure type. It then forwards it to the handler of the specified endpoint.

We currently support these failure types:

-

Error - fails the request with an error

-

CPU Load - creates a load on the CPU

-

Memory Leak - creates some memory which is never freed

-

Latency - pauses the request’s execution for a random amount of time

-

Disk Space - creates some temporary files on the machine

-

Goroutine Leak - creates and leaks goroutines

-

Panic - creates a panic in the request

-

Throttle - creates a rate limiter inside the request that rejects limit-exceeding requests

As an example, if a booking request goes to our booking service, we call GetVariable(“chaosFailure”) to determine if this request should succeed. The call contains all of the information required to make this decision (e.g. the request ID, IP address of the instance, etc). For Experimentation SDK implementation details, visit this blog post.

To promote chaos engineering among our engineers we built a great developer experience around it. Different engineering teams at Grab have expertise in different technologies and domains. So some might not have knowledge and skills to perform proper chaos experiments. But with our simplified user interface, they don’t have to worry about the underlying implementation.

Also, engineers who run chaos experiments are different experimentation platform users compared with our users like Product Analysts and Product Managers. Because of that, we provide a different experiment creation experience with a simple and specialised UI to configure new chaos experiments.

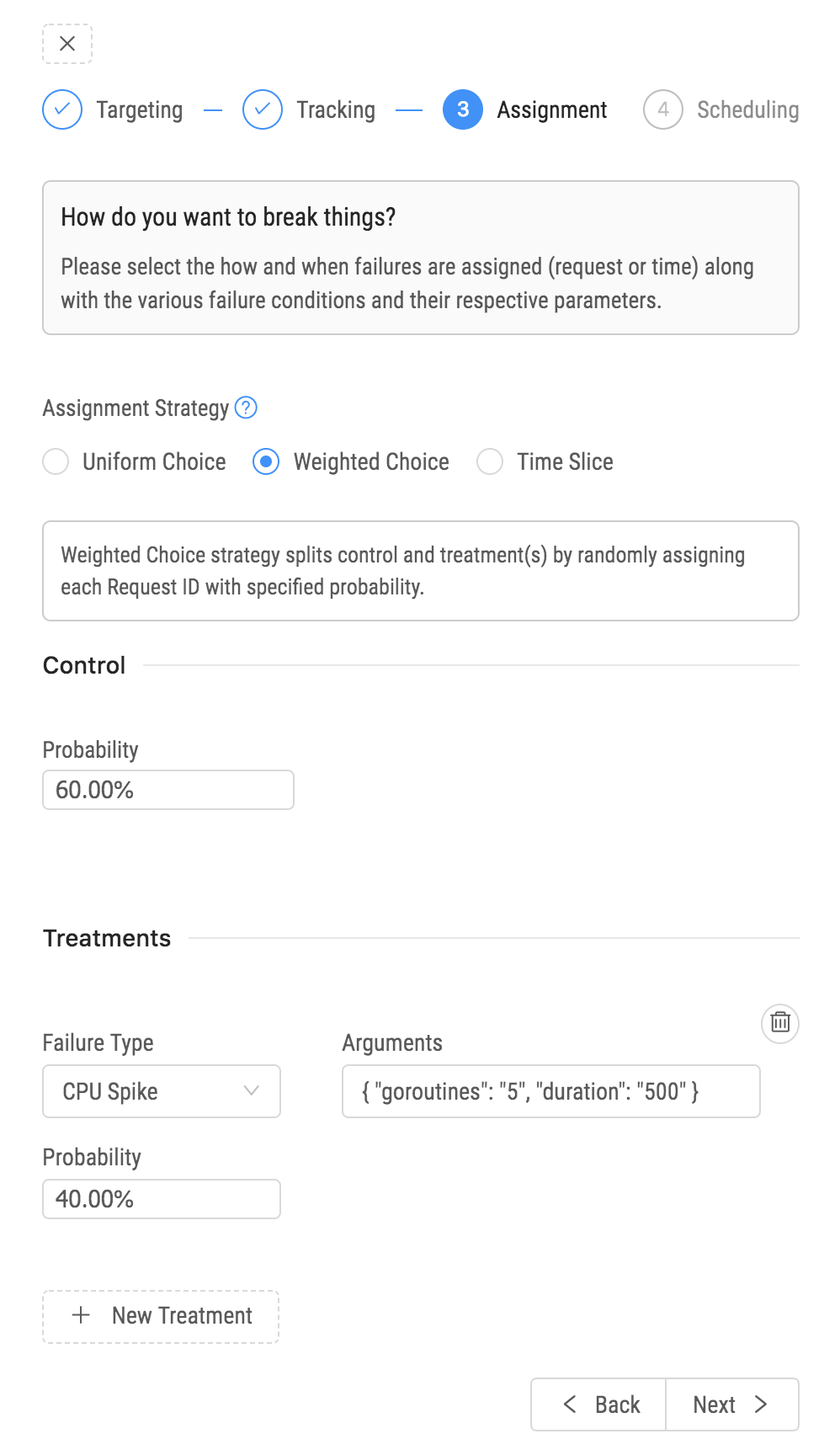

In the chaos engineering platform, an experiment has four steps:

-

Define the ideal state of the system’s normal behaviour.

-

Create a control configuration group and a treatment configuration group. A control group’s variables are assigned existing values. A treatment group’s variables are assigned new values.

-

Introduce real-world failures, like an increase in CPU load.

-

Find the statistically significant difference between the system’s correct and failed states.

To create a chaos experiment, target the service you want the experiment to break. You can further fine-grain this selection by providing the environment, availability zone, or a specific list of instances.

Next, specify a list of services affected by breaking the target service. You will closely monitor these services during the experiment. It helps to analyse the impact of the experiment later, though we continue tracking overall metrics indicating overall system health.

Next, we provide a UI to specify a strategy for dividing control and treatment groups, failure types, and configurations for each treatment. For the final step, provide a time duration and create the experiment. You’ve now added a chaos failure to your system and can monitor how it affects system behaviour.

Conclusions

After running a chaos experiment, there are typically two potential outcomes. You’ve verified your system is resilient to the introduced failure, or you’ve found a problem you need to fix. Both of these are good outcomes if the chaos experiment was first run on a staging environment. In the first case, you’ve increased your confidence in the system and its behaviour. In the other case, you’ve found a problem before it caused an outage.

Chaos Engineering is a tool to make your job easier. By proactively testing and validating your system’s failure modes you reduce your operational burden, increase your resiliency, and will sleep better at night.