Engineering

Engineering

Context Deadlines and How to Set Them

At Grab, our microservice architecture involves a huge amount of network traffic and inevitably, network issues will sometimes occur, causing API calls to fail or take longer than expected. We strive to make such incidents a non-event by designing with the expectation of such incidents in mind. With the aid of Go’s context package, we have improved upon basic timeouts by passing timeout information along the request path. However, this introduces extra complexity, and care must be taken to ensure timeouts are configured in a way that is efficient and does not worsen problems. This article explains from the ground up a strategy for configuring timeouts and using context deadlines correctly, drawing from our experience developing microservices in a large scale and often turbulent network environment.

Timeouts

Timeouts are a fundamental concept in computer networking. Almost every kind of network communication will have some kind of timeout associated with it, often configurable with a parameter. The idea is to place a time limit on some event happening, often a network response; after the limit has passed, the operation is aborted rather than waiting indefinitely. Examples of useful places to put timeouts include connecting to a database, making a HTTP request or on idle connections in a pool.

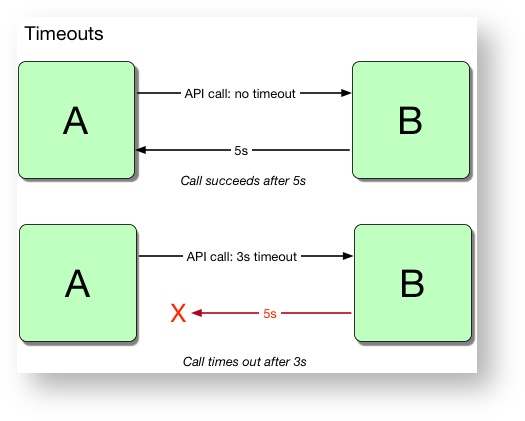

Figure 1.1: How timeouts prevent long API calls

Figure 1.1: How timeouts prevent long API calls

Timeouts allow a programme to continue where it otherwise might hang, providing a better experience to the end user. Often the default way for programs to handle timeouts is to return an error, but this doesn’t have to be the case: there are several better alternatives for handling timeouts which we’ll cover later.

While they may sound like a panacea, timeouts must be configured carefully to be effective: too short a timeout will result in increased errors from a resource which could still be working normally, and too long a timeout will risk consuming excess resources and a poor user experience. Furthermore, timeouts have evolved over time with new concepts such as Go’s context package, and the trend towards distributed systems has raised the stakes: timeouts are more important, and can cause more damage if misused!

Why Timeouts are Useful

In the context of microservices, timeouts are useful as a defensive measure against misbehaving or faulty dependencies. It is a guarantee that no matter how badly the dependency is failing, your call will never take longer than the timeout setting (for example 1 second). With so many other things to worry about, that’s a really nice thing to have! So there’s an instant benefit to your service’s resiliency, even if you do nothing more than set the timeout.

However, a service can choose what to do when it encounters a timeout, which can make them even more useful. Generally there are three options:

- Return an error. This is the simplest, but unless you know there is error handling upstream, this can actually deliver the worst user experience.

- Return a fallback value. We can return a default value, a cached value, or fall back to a simpler computed value. Depending on the circumstances, this can offer a better user experience.

- Retry. In the best case, a retry will succeed and deliver the intended response to the caller, albeit with the added timeout delay. However, there are other complexities to consider for retries to be effective. For a full discussion on this topic, see Circuit Breaker vs Retries Part 1and Circuit Breaker vs Retries Part 2.

At Grab, our services tend towards using retries wherever possible, to make minor errors as transparent as possible.

The main advantage of timeouts is that they give your service time to do something else, and this should be kept in mind when considering a good timeout value: not only do you want to allow the remote call time to complete (or not), but you need to allow enough time to handle the potential timeout as well.

Different Types of Timeouts

Not all timeouts are the same. There are different types of timeouts with crucial differences in semantics, and you should check the behaviour of the timeout settings in the library or resource you’re using before configuring them for production use.

In Go, there are three common classes of timeouts:

- Network timeouts: These come from the net package and apply to the underlying network connection. These are the best to use when available, because you can be sure that the network call has been cancelled when the call returns to your function.

- Context timeouts: Context is discussed later in this article, but for now just note that these timeouts are propagated to the server. Since the server is aware of the timeout, it can avoid wasted effort by abandoning computation after the timeout is reached.

- Asynchronous timeouts: These occur when a goroutine is executed and abandoned after some time. This does not automatically cancel the goroutine (you can’t really cancel goroutines without extra handling), so it risks leaking the goroutine and other resources. This approach should be avoided in production unless combined with some other measures to provide cancellation or avoid leaking resources.

Dangers of Poor Timeout Configuration for Microservice Calls

The benefits of using timeouts are enticing, but there’s no free lunch: relying on timeouts too heavily can lead to disastrous cascading failure scenarios. Worse, the effects of a poor timeout configuration often don’t become evident until it’s too late: it’s peak hour, traffic just reached an all-time high and… all your services froze up at the same time. Not good.

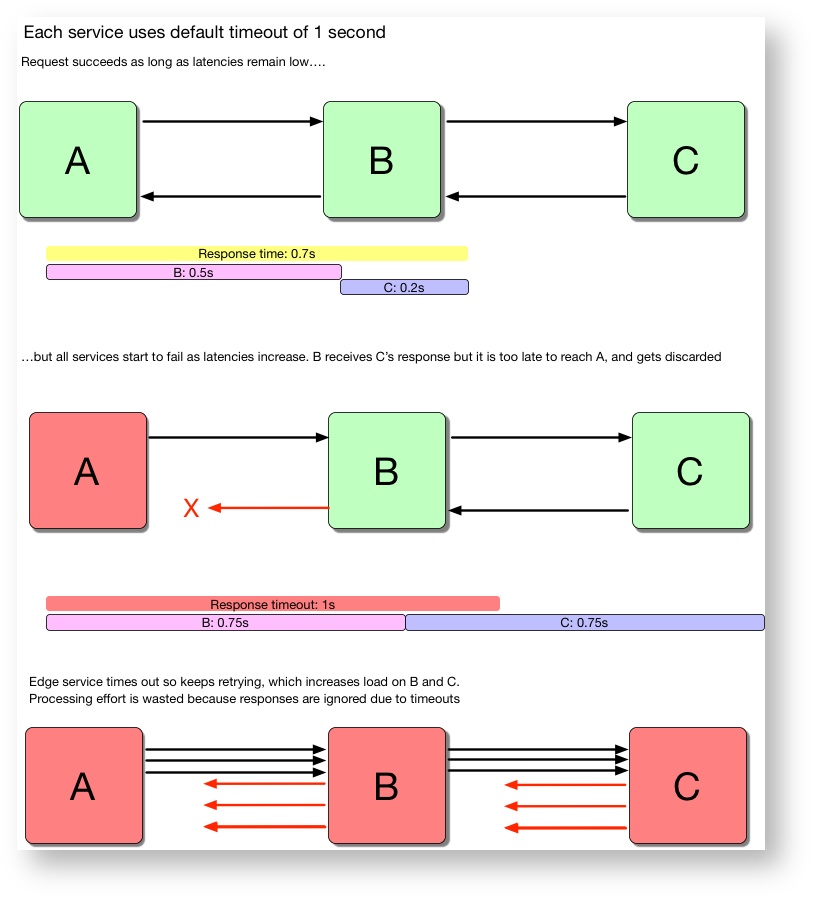

To demonstrate this effect, imagine a simple 3-service architecture where each service naively uses a default timeout of 1 second:

Figure 1.2: Example of how incorrect timeout configuration causes cascading failure

Figure 1.2: Example of how incorrect timeout configuration causes cascading failure

Service A’s timeout does not account for the fact that Service B calls C. If B itself is experiencing problems and takes 800ms to complete its work, then C effectively only has 200ms to complete before service A gives up. But since B’s timeout to C is also 1s, that means that C could be wasting up to 800ms of computational effort that ‘leaks’ - it has no chance of being used. Both B and C are blissfully unaware at first that anything is wrong - they happily return successful responses that A never receives!

This resource leak can soon be catastrophic, though: since the calls from B to A are timing out, A (or A’s clients) are likely to retry, causing the load on B to increase. This in turn causes the load on C to increase, and eventually all services will stop responding.

The same thing happens if B is healthy but C is experiencing problems: B’s calls to C will build up and cause B to become overloaded and fail too. This is a common cause of cascading failure.

How to Set a Good Timeout

Given the importance of correctly configuring timeout values, the question remains as to how to decide upon a ‘correct’ timeout value. If the timeout is for an API call to another service, a good place to start would be that service’s service-level agreements (SLAs). Often SLAs are based on latency percentiles, which is a value below which a given percentage of latencies fall. For example, a system might have a 99th percentile (also known as P99) latency of 300ms; this would mean that 99% of latencies are below 300ms. A high-order percentile such as P99 or even P99.9 can be used as a ballpark worst-case value.

Let’s say a service (B)’s endpoint has a 99th percentile latency of 600ms. Setting the timeout for this call at 600ms would guarantee that no calls take longer than 600ms, while returning errors for the rest and accepting an error rate of at most 1% (assuming the service is keeping to their SLA). This is an example of how the timeout can be combined with information about latencies to give predictable behaviour.

This idea can be taken further by considering retries too. If the median latency for this service is 50ms, then you could introduce a retry of 50ms for an overall timeout of 50ms + 600ms = 650ms:

Service B

Service B P99 latency SLA = 600ms

Service B median latency = 50ms

Service A

Request timeout = 600ms

Number of retries = 1

Retry request timeout = 50ms

Overall timeout = 50ms+600ms = 650ms

Chance of timeout after retry = 1% * 50% = 0.5%

This would still cut off the top 1% of latencies, while optimistically making another attempt for the median latency. This way, even for the 1% of calls that encounter a timeout, our service would still expect to return a successful response within 650ms more than half the time, for an overall success rate of 99.5%.

Context Propagation

Go officially introduced the concept of context in Go 1.7, as a way of passing request-scoped information across server boundaries. This includes deadlines, cancellation signals and arbitrary values. Let’s ignore the last part for now and focus on deadlines and cancellations. Often, when setting a regular timeout on a remote call, the server side is unaware of the timeout. Even if the server is notified indirectly when the client closes the connection, it’s still not necessarily clear whether the client timed out or encountered another issue. This can lead to wasted resources, because without knowing the client timed out, the server often carries on regardless. Context aims to solve this problem by propagating the timeout and context information across API boundaries.

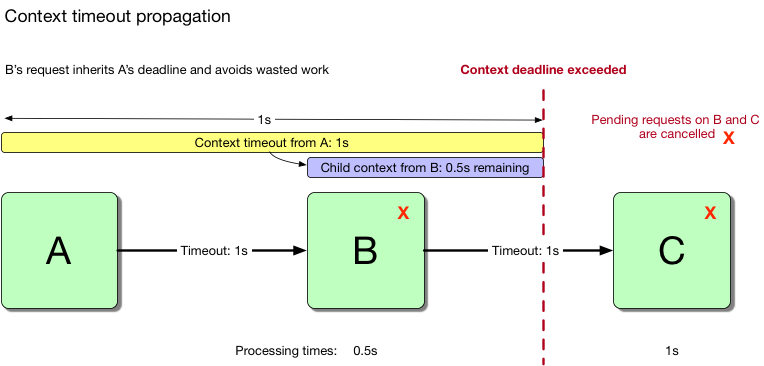

Figure 1.4: Context propagation cancels work on B and C

Figure 1.4: Context propagation cancels work on B and C

Server A sets a context timeout of 1 second. Since this information spans the entire request and gets propagated to C, C is always aware of the remaining time it has to do useful work - work that won’t get discarded. The remaining time can be defined as (1 - b), where b is the amount of time that server B spent processing before calling C. When the deadline is exceeded, the context is immediately cancelled, along with any child contexts that were created from the parent.

The context timeout can be a relative time (eg. 3 seconds from now) or an absolute time (eg. 7pm). In practice they are equivalent, and the absolute deadline can be queried from a timeout created with a relative time and vice-versa.

Another useful feature of contexts is cancellation. The client has the ability to cancel the request for any reason, which will immediately signal the server to stop working. When a context is cancelled manually, this is very similar to a context being cancelled when it exceeds the deadline. The main difference is the error message will be ‘context cancelled’ instead of ‘context deadline exceeded’. This is a common cause of confusion, but context cancelled is always caused by an upstream client, while deadline exceeded could be a deadline set upstream or locally.

The server must still listen for the ‘context done’ signal and implement cancellation logic, but at least it has the option of doing so, unlike with ordinary timeouts. The most common reason for cancelling a request is because the client encountered an error and no longer needs the response that the server is processing. However, this technique can also be used in request hedging, where concurrent duplicate requests are sent to the server to decrease the impact of an individual call experiencing latency. When the first response returns, the other requests are cancelled because they are no longer needed.

Context can be seen as ‘distributed timeouts’ - an improvement to the concept of timeouts by propagating them. But while they achieve the same goal, they introduce other issues that must be considered.

Context Propagation and Timeout Configuration

When propagating timeout information via context, there is no longer a static ‘timeout’ setting per call. This can complicate debugging: even if the client has correctly configured their own timeout as above, a context timeout could mean that either the remote downstream server is slow, or that an upstream client was slow and there was insufficient time remaining in the propagated context!

Let’s revisit the scenario from earlier, and assume that service A has set a context timeout of 1 second. If B is still taking 800ms, then the call to C will time out after 200ms. This changes things completely: although there is no longer the resource leak (because both B and C will terminate the call once the context timeout is exceeded), B will have an increase in errors whereas previously it would not (at least until it became overloaded). This may be worse than completing the request after A has given up, depending on the circumstances. There is also a dangerous interaction with circuit breakers which we will discuss in the next section.

If allowing the request to complete is preferable to cancelling it even in the event of a client timeout, the request should be made with a new context decoupled from the parent (ie. context.Background()). This will ensure that the timeout is not propagated to the remote service. When doing this, it is still a good idea to set a timeout, to avoid waiting indefinitely for it to complete.

Context and Circuit-breakers

A circuit-breaker is a software library or function which monitors calls to external resources with the aim of preventing calls which are likely to fail, ‘short-circuiting’ them (hence the name). It is a good practice to use a circuit-breaker for all outgoing calls to dependencies, especially potentially unreliable ones. But when combined with context propagation, that raises an important question: should context timeouts or cancellation cause the circuit to open?

Let’s consider the options. If ‘yes’, this means the client will avoid wasting calls to the server if it’s repeatedly hitting the context timeout. This might seem desirable at first, but there are drawbacks too.

Pros:

- Consistent behaviour with other server errors

- Avoids making calls that are unlikely to succeed

- It is obvious when things are going wrong

- Client has more time to fall back to other behaviour

- More lenient on misconfigured timeouts because circuit-breaking ensures that subsequent calls will fail fast, thus avoiding cascading failure

Cons:

- Unpredictable

- A misconfigured upstream client can cause the circuit to open for all other clients

- Can be misinterpreted as a server error

It is generally better not to open the circuit when the context deadline set upstream is exceeded. The only timeout allowed to trigger the circuit-breaker should be the request timeout of the specific call for that circuit.

Pros:

- More predictable

- Circuit depends mostly on server health, not client

- Clients are isolated

Cons:

- May be confusing for clients who expect the circuit to open

- Misconfigured timeouts are more likely to waste resources

Note that the above only applies to propagated contexts. If the context only spans a single individual call, then it is equivalent to a static request timeout, and such errors should cause circuits to open.

How to Set Context Deadlines

Let’s recap some of the concepts covered in this article so far:

- Timeouts are a time limit on an event taking place, such as a microservice completing an API call to another service.

- Request timeouts refer to the timeout of a single individual request. When accounting for retries, an API call may include several request timeouts before completing successfully.

- Context timeouts are introduced in Go to propagate timeouts across API boundaries.

- A context deadline is an absolute timestamp at which the context is considered to be ‘done’, and work covered by this context should be cancelled when the deadline is exceeded.

Fortunately, there is a simple rule for correctly configuring context timeouts:

The upstream timeout must always be longer than the total downstream timeouts including retries.

The upstream timeout should be set at the ‘edge’ server and cascade throughout.

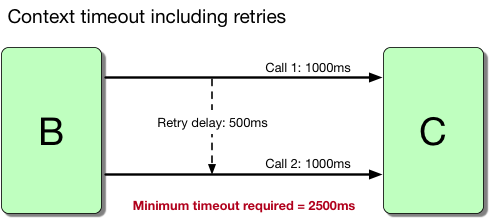

In our scenario, A is the edge server. Let’s say that B’s timeout to C is 1s, and it may retry at most once, after a delay of 500ms. The appropriate context timeout (CT) set from A can be calculated as follows:

CT(A) = (timeout to C * number of attempts) + (retry delay * number of retries)

CT(A) = (1s * 2) + (500ms * 1) = 2,500ms

Figure 1.5: Formula for calculating context timeouts

Figure 1.5: Formula for calculating context timeouts

Extra time can be allocated for B’s processing time and to allow B to return a fallback response if appropriate.

Note that if A configures its timeout according to this rule, then many of the above issues disappear. There are no wasted resources, because B and C are given the maximum time to complete their requests successfully. There is no chance for B’s circuit-breaker to open unexpectedly, and cascading failure is mostly avoided: a failure in C will be handled and be returned by B, instead of A timing out as well.

A possible alternative would be to rely on context cancellation: allow A to set a shorter timeout, which cancels B and C if the timeout is exceeded. This is an acceptable approach to avoiding cascading failure (and cancellation should be implemented in any case), but it is less optimal than configuring timeouts according to the above formula. One reason is that there is no guarantee of the downstream services handling the timeout gracefully; as mentioned previously, the service must explicitly check for ctx.Done() and this is rarely followed in practice. It is also impractical to place checks at every point in the code, so there could be a considerable delay between the client cancellation and the server abandoning the processing.

A second reason not to set shorter timeouts is that it could lead to unexpected errors on the downstream services. Even if B and C are healthy, a shorter context timeout could lead to errors if A has timed out. Besides the problem of having to handle the cancelled requests, the errors could create noise in the logs, and more importantly could have been avoided. If the downstream services are healthy and responding within their SLA, there is no point in timing out earlier. An exception might be for the edge server (A) to allow for only 1 attempt or fewer retries than the downstream service actually performs. But this is tricky to configure and weakens the resiliency. If it is desirable to shorten the timeouts to decrease latency, it is better to start adjusting the timeouts of the downstream resources first, starting from the innermost service outwards.

A Model Implementation for Using Context Timeouts in Calls Between Microservices

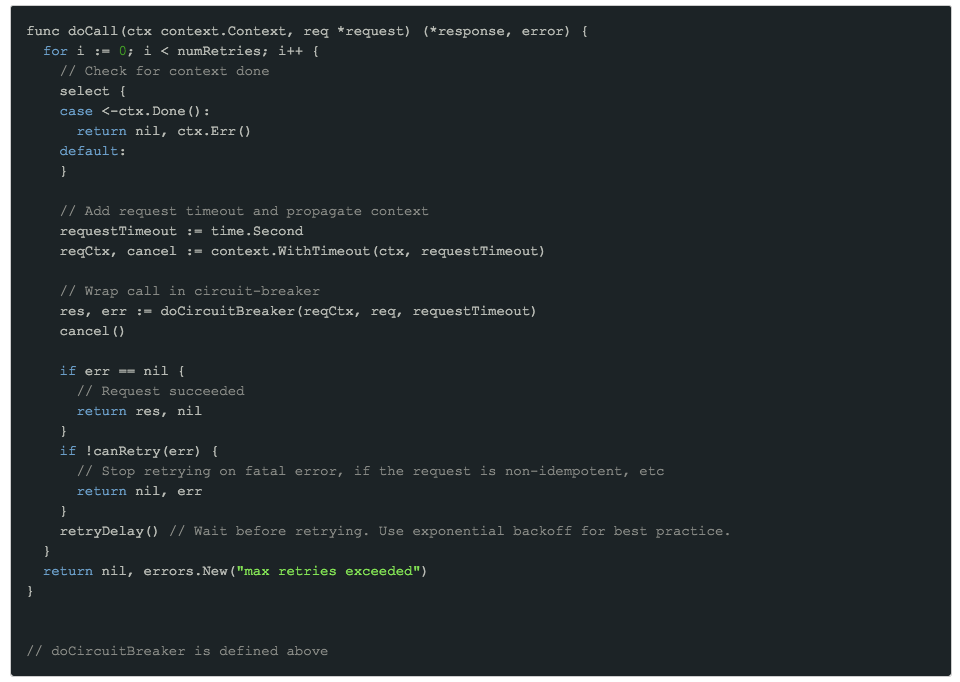

We’ve touched on several useful concepts for improving resiliency in distributed systems: timeouts, context, circuit-breakers and retries. It is desirable to use all of them together in a good resiliency strategy. However, the actual implementation is far from trivial; finding the right order and configuration to use them effectively can seem like searching for the holy grail, and many teams go through a long process of trial and error, continuously improving their implementation. Let’s try to formally put together an ideal implementation, step by step.

Note that the code below is not a final or production-ready implementation. At Grab we have developed independent circuit-breaker and retry libraries, with many settings that can be configured for fine-tuning. However, it should serve as a guide for writing resilient client libraries.

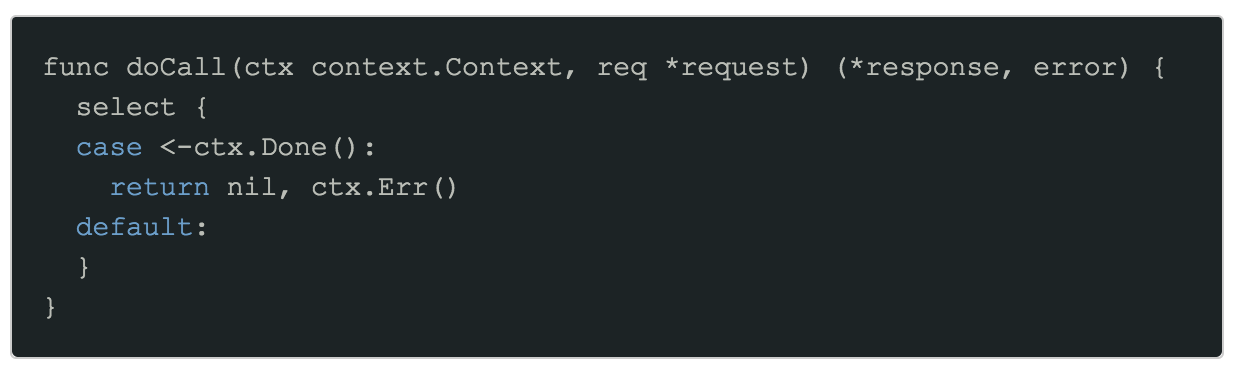

Step 1: Context propagation

The skeleton function signature includes a context object as the first parameter, which is the best practice intended by Google. We check whether the context is already done before proceeding, in which case we ‘fail fast’ without wasting any further effort.

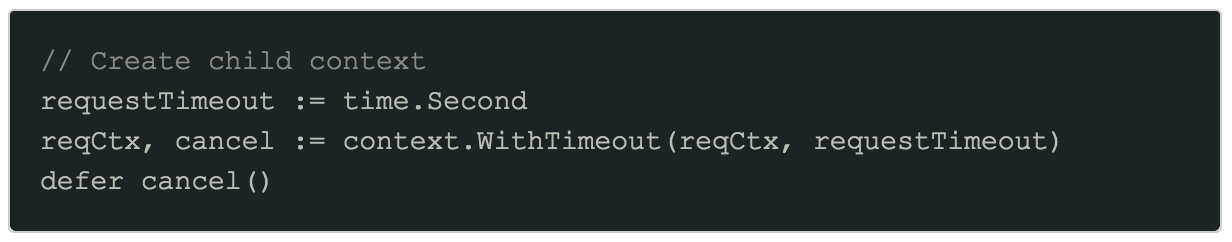

Step 2: Create child context with request timeout

Our service has no control over the parent context. Indeed, it could have no deadline at all! Therefore it’s important to create a new context and timeout for our own outgoing request as well, using WithTimeout. It is mandatory to call the returned cancel function to ensure the context is properly cancelled and avoid a goroutine leak.

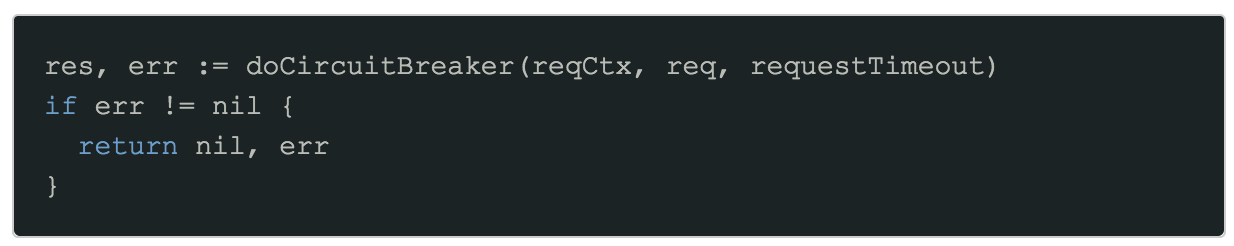

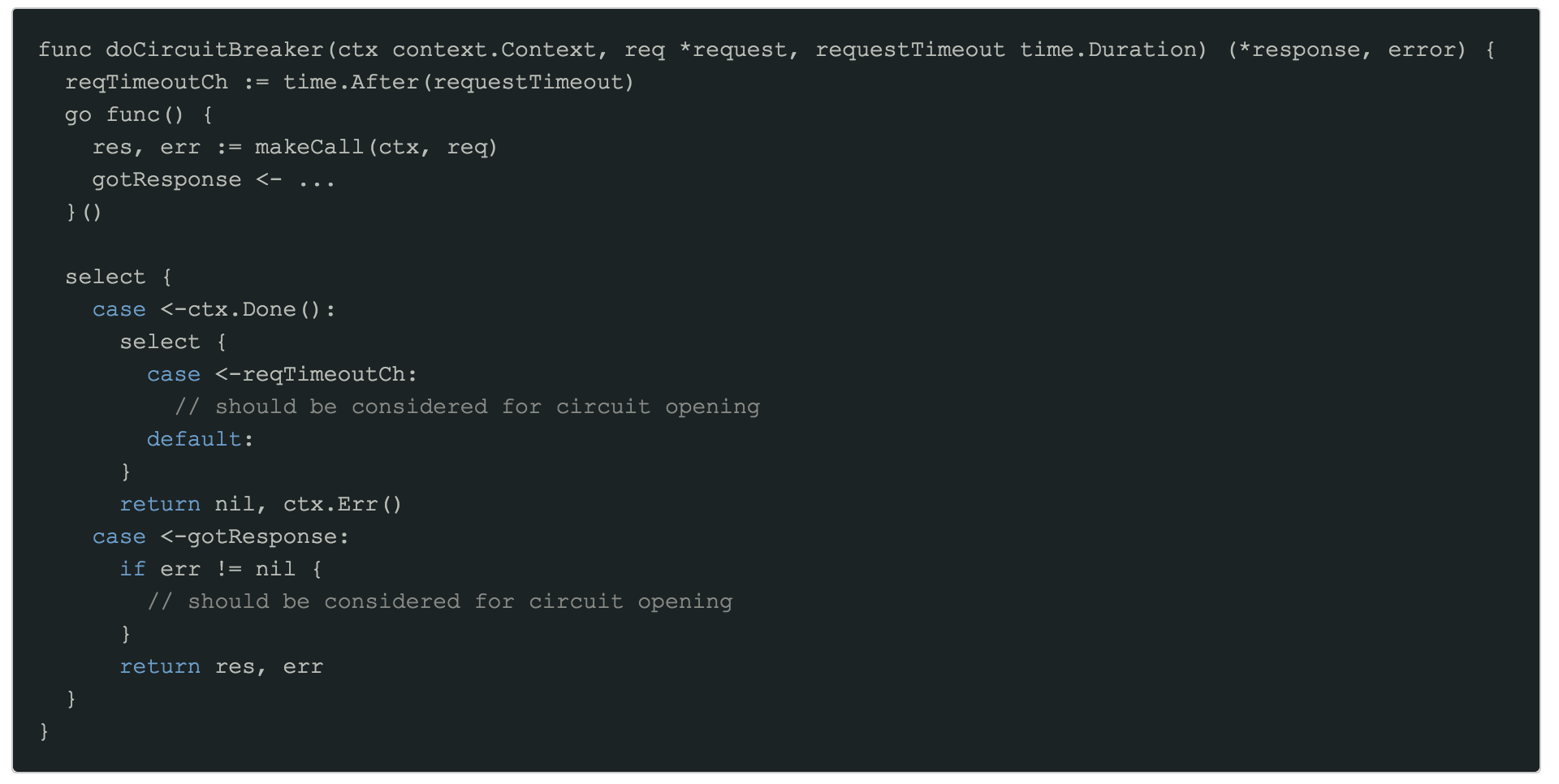

Step 3: Introduce circuit-breaker logic

Next, we wrap our call to the external service in a circuit-breaker. The actual circuit-breaker implementation has been omitted for brevity, but there are two important points to consider:

- It should only consider opening the circuit-breaker when requestTimeout is reached, not on

ctx.Done(). - The circuit name should ideally be unique for this specific endpoint

Step 4: Introduce retries

The last step is to add retries to our request in the case of error. This can be implemented as a simple for loop, but there are some key things to include in a complete retry implementation:

ctx.Done()should be checked after each retry attempt to avoid wasting a call if the client has given up.- The request context should be cancelled before the next retry to avoid duplicate concurrent calls and goroutine leaks.

- Not all kinds of requests should be retried.

- A delay should be added before the next retry, using exponential backoff.

- See Circuit Breaker vs Retries Part 2 for a thorough guide to implementing retries.

Step 5: The complete implementation

And here we have arrived at our ‘ideal’ implementation of an external call including context handling and propagation, two levels of timeout (parent and request), circuit-breaking and retries. This should be sufficient for a good level of resiliency, avoiding wasted effort on both the client and server.

As a future enhancement, we could consider introducing a ‘minimum time per request’, which the retry loop should use to check for remaining time as well as ctx.Done() (but not instead - we need to account for client cancellation too). Of course metrics, logging and error handling should also be added as necessary.

Important Takeaways

To summarise, here are a few of the best practices for working with context timeouts:

Use SLAs and latency data to set effective timeouts

Having a default timeout value for everything doesn’t scale well. Use available information on SLAs and historic latency to set timeouts that give predictable results.

Understand the common error messages

The context canceled (context.Canceled) error occurs when the context is manually cancelled. This automatically cancels any child contexts attached to the parent. It is rare for this error to surface on the same service that triggered the cancellation; if cancel is called, it is usually because another error has been detected (such as a timeout) which would be returned instead. Therefore, context canceled is usually caused by an upstream error: either the client timed out and cancelled the request, or cancelled the request because it was no longer needed, or closed the connection (this typically results in a cancelled context from Go libraries).

The context deadline exceeded error occurs only when the time limit was reached. This could have been set locally (by the server processing the request) or by an upstream client. Unfortunately, it’s often difficult to distinguish between them, although they should generally be handled in the same way. If a more granular error is required, it is recommended to use child contexts and explicitly check them for ctx.Done(), as shown in our model implementation.

Check for ctx.Done() before starting any significant work

Don’t enter an expensive block of code without checking the context; if the client has already given up, the work will be wasted.

Don’t open circuits for context errors

This leads to unpredictable behaviour, because there could be a number of reasons why the context might have been cancelled. Only context errors due to request timeouts originating from the local service should lead to circuit-breaker errors.

Set context timeouts at the edge service, using a cascading timeout budget

The upstream timeout must always be longer than the total downstream timeouts. Following this formula will help to avoid wasted effort and cascading failure.

In Conclusion

Go’s context package provides two extremely valuable tools that complement timeouts: deadline propagation and cancellation. This article has shown the benefits of using context timeouts and how to correctly configure them in a multi-server request path. Finally, we have discussed the relationship between context timeouts and circuit-breakers, proposing a model implementation for integrating them together in a common library.

If you have a Go server, chances are it’s already making heavy use of context. If you’re new to Go or had been confused by how context works, hopefully this article has helped to clarify misunderstandings. Otherwise, perhaps some of the topics covered will be useful in reviewing and improving your current context handling or circuit-breaker implementation.