A Key Expired in Redis, You Won't Believe What Happened Next

One of Grab’s more popular caching solutions is Redis (often in the flavour of the misleadingly named ElastiCache 1), and for most cases, it works. Except for that time it didn’t. Follow our story as we investigate how Redis deals with consistency on key expiration.

A recent problem we had with our ElastiCache Redis involving our Unicorn API, was that we were serving unusually outdated Unicorns to our clients.

Unicorns are in popular demand and change infrequently, and as a result, Grab Unicorns are cached at almost every service level. Unfortunately, consumers typically like having shiny new unicorns as soon as they are spotted, so we had to make sure we bound our Unicorn change propagation time. In this particular case, we found that apart from the usual minuscule DB replication lag, a region-specific change in Unicorns took up to 60 minutes to reach our consumers.

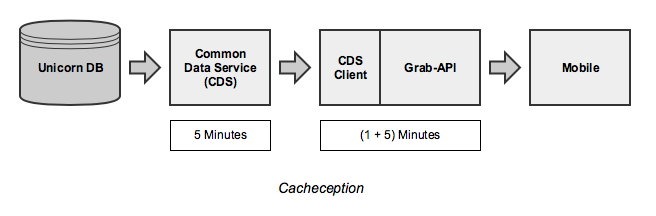

Considering that our Common Data Service (CDS) server cache (5 minutes), CDS client cache (1 minute), Grab API cache (5 minutes), and mobile cache (varies, but insignificant) together accounted for at most ~11 minutes of Unicorn change propagation time, this was a rather perplexing find. (Also, we should really consider an inter-service cache invalidation strategy for this 2.)

How We Cache Unicorns at the API Level

Subsequently, we investigated why the Unicorns returned from the API were up to 45 minutes stale, as tested on production. Before we share our findings, let’s go through a quick overview of what the Unicorn API’s ElastiCache Redis looks like.

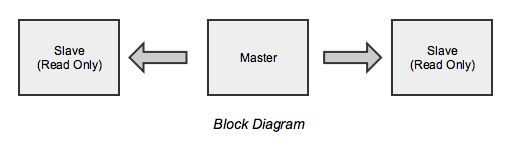

We have a master node used exclusively for writes, and 2 read-only slaves 3. This is also a good time to mention that we use Redis 2.x as ElastiCache support for 3.x was only added in October 2016.

As Unicorns are region-specific, we were caching Unicorns based on locations, and consequently, have a rather large number of keys in this Redis (~5594518 at the time). This is also why we encountered cases where different parts of the same city inexplicably had different Unicorns.

So What Gives?

As part of our investigation, we tried monitoring the TTLs (Time To Live) on some keys in the Redis.

Steps (on the master node):

- Run TTL for a key, and monitor the countdown to expiry

- Starting from 300 (seconds), it counted down to 0

- After expiry, it returned -2 (expected behaviour)

- Running GET on an expired key returned nothing

- Running a GET on the expired key in a slave returned nothing

Interestingly, running the same experiment on the slave yielded different behaviour.

Steps (on a slave node):

- Run TTL for a key, and monitor the countdown to expiry

- Starting from 300 (seconds), it counted down to 0

- After expiry, it returned -2 (expected behaviour)

- Running GET on an expired key returned data!

- Running GET for the key on master returned nothing

- Subsequent GETs on the slave returned nothing

This finding, together with the fact that we don’t read from the master branch, explained how we ended up with Unicorn ghosts, but not why.

To understand this better, we needed to RTFM. More precisely, we need two key pieces of information.

How EXPIREs are Managed Between Master and Slave Nodes on Redis 2.x

To “maintain consistency”, slaves aren’t allowed to expire keys unless they receive a DEL from the master branch, even if they know the key is expired. The only exception is when a slave becomes master 4. So basically, if the master doesn’t send a DEL to the slave, the key (which might have been set with a TTL using the Redis API contract), is not guaranteed to respect the TTL it was set with. This is when you scale to have read slaves, which, apparently, is a shocking requirement in production systems.

How EXPIREs are Managed for Keys that aren’t “Gotten from Master”

Since every key needs to be deleted on master first, and some of our keys were expired correctly, there had to be a “passive” manner in which Redis was deleting expired keys that didn’t involve an explicit GET command from the client. The manual 5:

Redis keys are expired in two ways: a passive way, and an active way.

A key is passively expired simply when some client tries to access it, and the key is found to be timed out.

Of course this is not enough as there are expired keys that will never be accessed again. These keys should be expired anyway, so periodically Redis tests a few keys at random among keys with an expire set. All the keys that are already expired are deleted from the keyspace.

Specifically this is what Redis does 10 times per second:

- Test 20 random keys from the set of keys with an associated expire.

- Delete all the keys found expired.

- If more than 25% of keys were expired, start again from step 1.

This is a trivial probabilistic algorithm, basically the assumption is that our sample is representative of the whole key space, and we continue to expire until the percentage of keys that are likely to be expired is under 25%.

This means that at any given moment the maximum amount of keys already expired that are using memory is at max equal to max amount of write operations per second divided by 4.

So that’s 200 keys tested for expiry each second on the master branch, and about 25% of your keys on the slaves guaranteed to be serving dead Unicorns, because they didn’t get the memo.

While 200 keys might be enough to make it through a hackathon project blazingly fast, it certainly isn’t fast enough at our scale, to expire 25% of our 5594518 keys in time for Unicorn updates.

Doing The Math

Number of expired keys (at iteration 0) = e0

Total number of keys = s

Probability of choosing an expired key (p) = e0 / s

Assuming Binomial trials, the expected number of expired keys chosen in n trials:

E = n * p

Number of expired keys for next iteration =

e0 - E = e0 - n * (e0 / s) = e0 * (1 - n / s)

Number of expired keys at the end of iteration k:

ek = e0 * (1 - n / s)k

So to have fewer than 1 expired key,

e0 * (1 - n / s)k < 1

=> k < ln(1 / e0) / ln(1 - n / s)

Assuming we started with 25% keys expired, we plug in:

e0 = 0.25 * 5594518, n = 20, s = 5594518

We obtain a value of k around 3958395. Since this is repeated 10 times a second, it would take roughly 110 hours to achieve this (as ek is a decreasing function of k).

The Bottom Line

At our scale, and assuming >25% expired keys at the beginning of time, it would take at least 110 hours to guarantee no expired keys in our cache.

What We Learnt

- The Redis author pointed out and fixed this issue in a later version of Redis 6

- Upgrade our Redis more often

- Pay more attention to cache invalidation expectations and strategy during software design

Many thanks to Althaf Hameez, Ryan Law, Nguyen Qui Hieu, Yu Zezhou and Ivan Poon who reviewed drafts and waited patiently for it to be published.

Footnotes

-

ElastiCache is hardly elastic, considering your “scale up” is a deliberate process involving backup, replicate, deploy, and switch, during which time your server is serving peak hour teapots (as reads and writes may be disabled). http://docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonElastiCache/latest/UserGuide/Scaling.html ↩

-

Turns out that streaming solutions are rather good at this, when we applied them to some of our non-Unicorn offerings. (Writes are streamed, and readers listen and invalidate their cache as required.) ↩

-

This, as it turns out, is a bad idea. In case of failovers, AWS updates the master address to point to the new master, but this is not guaranteed for the slaves. So we could end up with an unused slave and a master with reads + writes in the worst case (unless we add some custom code to manage the failover). Best practice is to have read load distributed on master as well. ↩

-

https://redis.io/commands/expire#how-expires-are-handled-in-the-replication-link-and-aof-file ↩

-

https://github.com/antirez/redis/issues/1768 (TL;DR: Slaves now use local clock to return null to clients when it thinks keys are expired. The trade-off is the possibility of early expires if a slave’s clock is faster than the master.) ↩