Engineering

Engineering

Designing Resilient Systems Beyond Retries (Part 3): Architecture Patterns and Chaos Engineering

This post is the third of a three-part series on going beyond retries and circuit breakers to improve system resiliency. This whole series covers techniques and architectures that can be used as part of a strategy to improve resiliency. In this article, we will focus on architecture patterns and chaos engineering to reduce, prevent, and test resiliency.

Reducing Failure Through Architecture Patterns

Resiliency is all about preparing for and handling failure. So the most effective way to improve resiliency is undoubtedly to reduce the possible ways in which failure can occur, and several architectural patterns have emerged with this aim in mind. Unfortunately these are easier to apply when designing new systems and less relevant to existing ones, but if resiliency is still an issue and no other techniques are helping, then refactoring the system is a good approach to consider.

Idempotency

One popular pattern for improving resiliency is the concept of idempotency. Strictly speaking, an idempotent endpoint is one which always returns the same result given the same parameters, no matter how many times it is called. However, the definition is usually extended to mean it returns the results and has no side-effects, or any side-effects are only executed once. The main benefit of making endpoints idempotent is that they are always safe to retry, so it complements the retry technique to make it more effective. It also means there is less chance of the system getting into an inconsistent or worse state after experiencing failure.

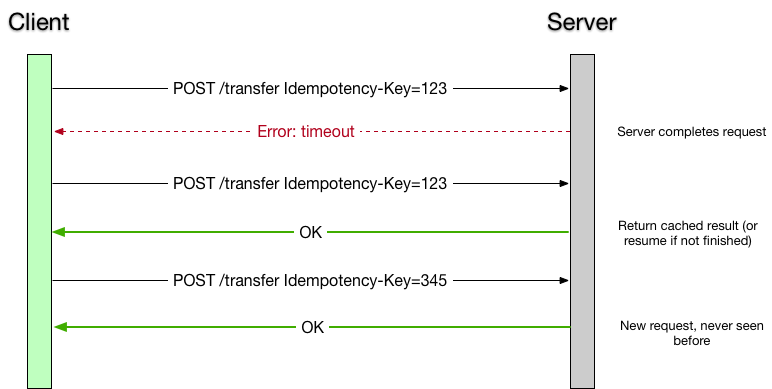

If an operation has side-effects but cannot distinguish unique calls with its current parameters, it can be made to be idempotent by adding an idempotency key parameter. The classic example is money: a ‘transfer money to X’ operation may legitimately occur multiple times with the same parameters, but making the same call twice would be a mistake, so it is not idempotent. A client would not be able to retry a call that timed out, because it does not know whether or not the server processed the request. However, if the client generates and sends a unique ID as an idempotency key parameter, then it can safely retry. The server can then use this information to determine whether to process the request (if it sees the request for the first time) or return the result of the previous operation.

Using idempotency keys can guarantee idempotency for endpoints with side-effects

Using idempotency keys can guarantee idempotency for endpoints with side-effects

Asynchronous Responses

A second pattern is making use of asynchronous responses. Rather than relying on a successful call to a dependency which may fail, a service may complete its own work and return a successful or partial response to the client. The client would then have to receive the response in an alternate way, either by polling (‘pull’) until the result is ready or the response being ‘pushed’ from the server when it completes.

From a resiliency perspective, this guarantees that the downstream errors do not affect the endpoint. Furthermore, the risk of the dependency causing latency or consuming resources goes away, and it can be retried in the background until it succeeds. The disadvantage is that this works against the ‘fail fast’ principle, since the call might be retried indefinitely without ever failing. It might not be clear to the client what to do in this case.

Not all endpoints have to be made asynchronous, and the decision to be synchronous or not could be made by the endpoint dynamically, depending on the service health. Work that can be made asynchronous is known as deferrable work, and utilising this information can save resources and allow the more critical endpoints to complete. For example, a fraud system may decide whether or not a newly registered user should be allowed to use the application, but such decisions are often complex and costly. Rather than slow down the registration process for every user and create a poor first impression, the decision can be made asynchronously. When the fraud-decision system is available, it picks up the task and processes it. If the user is then found to be fraudulent, their account can be deactivated at that point.

Preventing Disaster Through Chaos Engineering

It is famously understood that disaster recovery is worthless unless it’s tested regularly. There are dozens of stories of employees diligently performing backups every day only to find that when they actually needed to restore from it, the backups were empty. The same thing applies to resiliency, albeit with less spectacular consequences.

The emerging best practice for testing resiliency is chaos engineering. This practice, made famous by Netflix’s Chaos Monkey, is the idea of deliberately causing parts of a system to fail in order to test (and subsequently improve) its resiliency. There are many different kinds of chaos engineering that vary in scope, from simulating an outage in an entire AWS region to injecting latency into a single endpoint. A chaos engineering strategy may include multiple types of failure, to build confidence in the ability of various parts of the system to withstand failure.

Chaos engineering has evolved since its inception, ironically becoming less ‘chaotic’, despite the name. Shutting off parts of a system without a clear plan is unlikely to provide much value, but is practically guaranteed to frustrate your consumers - and upper management! Since it is recommended to experiment on production, minimising the blast radius of chaos experiments, at least at the beginning, is crucial to avoid unnecessary impact to the system.

Chaos Experiment Process

The basic process for conducting a chaos experiment is as follows:

- Define how to measure a ‘steady state’, in order to confirm that the system is currently working as expected.

- Decide on a ‘control group’ (which does not change) and an ‘experiment group’ from the pool of backend servers.

- Hypothesise that the steady state will not change during the experiment.

- Introduce a failure in one component or aspect of the system in the control group, such as the network connection to the database.

- Attempt to disprove the hypothesis by analysing the difference in metrics between the control and experiment groups.

If the hypothesis is disproved, then the parts of the system which failed are candidates for improvement. After making changes, the experiments are run again, and gradually confidence in the system should improve.

Chaos experiments should ideally mimic real-world scenarios that could actually happen, such as a server shutting down or a network connection being disconnected. These events do not necessarily have to be directly related to failure - ordinary events such as auto-scaling or a change in server hardware or VM type can be experimented with, as they could still potentially affect the steady state.

Finally, it is important to automate as much of the chaos experiment process as possible. From setting up the control group to starting the experiment and measuring the results, to automatically disabling the experiment if the impact to production has exceeded the blast radius, the investment in automating them will save valuable engineering time and allow for experiments to eventually be run continuously.

Conclusion

Retries are a useful and important part of building resilient software systems. However, they only solve one part of the resiliency problem, namely recovery. Recovery via retries is only possible under certain conditions and could potentially exacerbate a system failure if other safeguards aren’t also in place. Some of these safeguards and other resiliency patterns have been discussed in this article.

The excellent Hystrix library combines multiple resiliency techniques, such as circuit-breaking, timeouts and bulkheading, in a single place. But even Hystrix cannot claim to solve all resiliency issues, and it would not be wise to rely on a single library completely. However, just as it can’t be recommended to only use Hystrix, suddenly introducing all of the above patterns isn’t advisable either. There is a point of diminishing returns with adding more; more techniques means more complexity, and more possible things that could go wrong.

Rather than implement all of the resiliency patterns described above, it is recommended to selectively apply patterns that complement each other and cover existing gaps that have previously been identified. For example, an existing retry strategy can be enhanced by gradually switching to idempotent endpoints, improving the coverage of API calls that can be retried.

A microservice architecture is a good foundation for building a resilient system, but it requires careful planning and implementation to achieve. By identifying the possible ways in which a system can fail, then evaluating and applying the tried-and-tested patterns to withstand them, a reliable system can become one that is truly resilient.

I hope you found this series useful. Comments are always welcome.