Engineering

Engineering

Building Grab’s Experimentation Platform

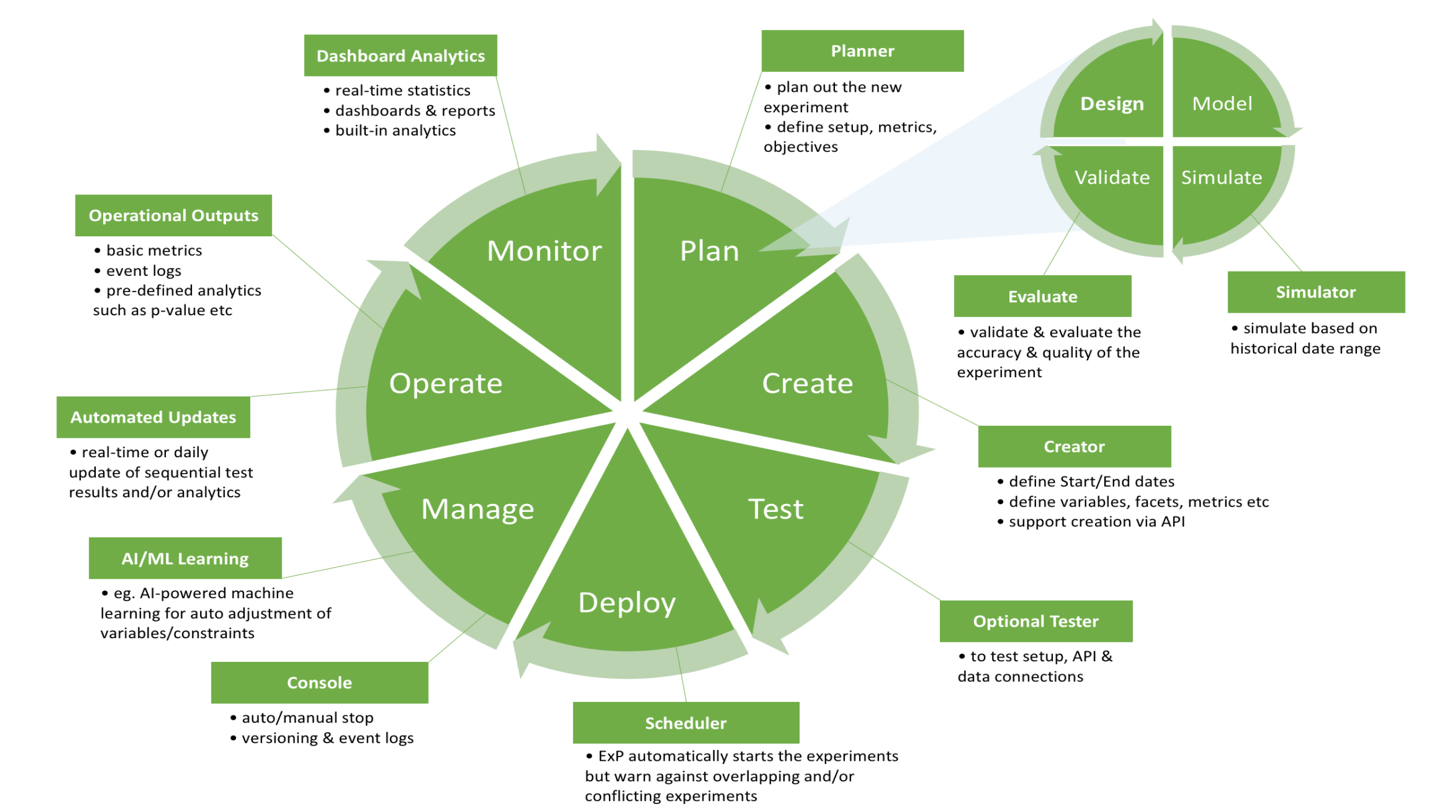

ExP Overview

At Grab, we continuously strive to improve the user experience of our app for both our passengers and driver-partners.

To do that, we’re constantly experimenting, and in fact, many of the improvements we roll out to the Grab app are a direct result of successful experiments.

However, running many experiments at the same time can be a messy, complicated and expensive process. That is why we created the Grab experimentation platform (ExP), to provide clean and simple ways to identify opportunities, create prototypes, perform experiments, refine, and launch products. Before rolling out new Grab features, ExP enables us to run controlled experiments to test the effectiveness of the new feature. The goal of ExP is to make sure that new features roll out without any hiccups and causal relationships are analysed correctly.

Experimentation helps development teams determine if they’re building the right product. It allows the team to scrap an idea early on if it doesn’t make a positive impact. This avoids wastage of precious resources. By adopting experimentation, teams eliminate uncertainty and guesswork from their product development process; thus avoiding long development cycles. By introducing a new version of our app to only a select group of consumers, teams can quickly assess if their new updates are improvements or regressions. This allows for better recovery and damage control if necessary.

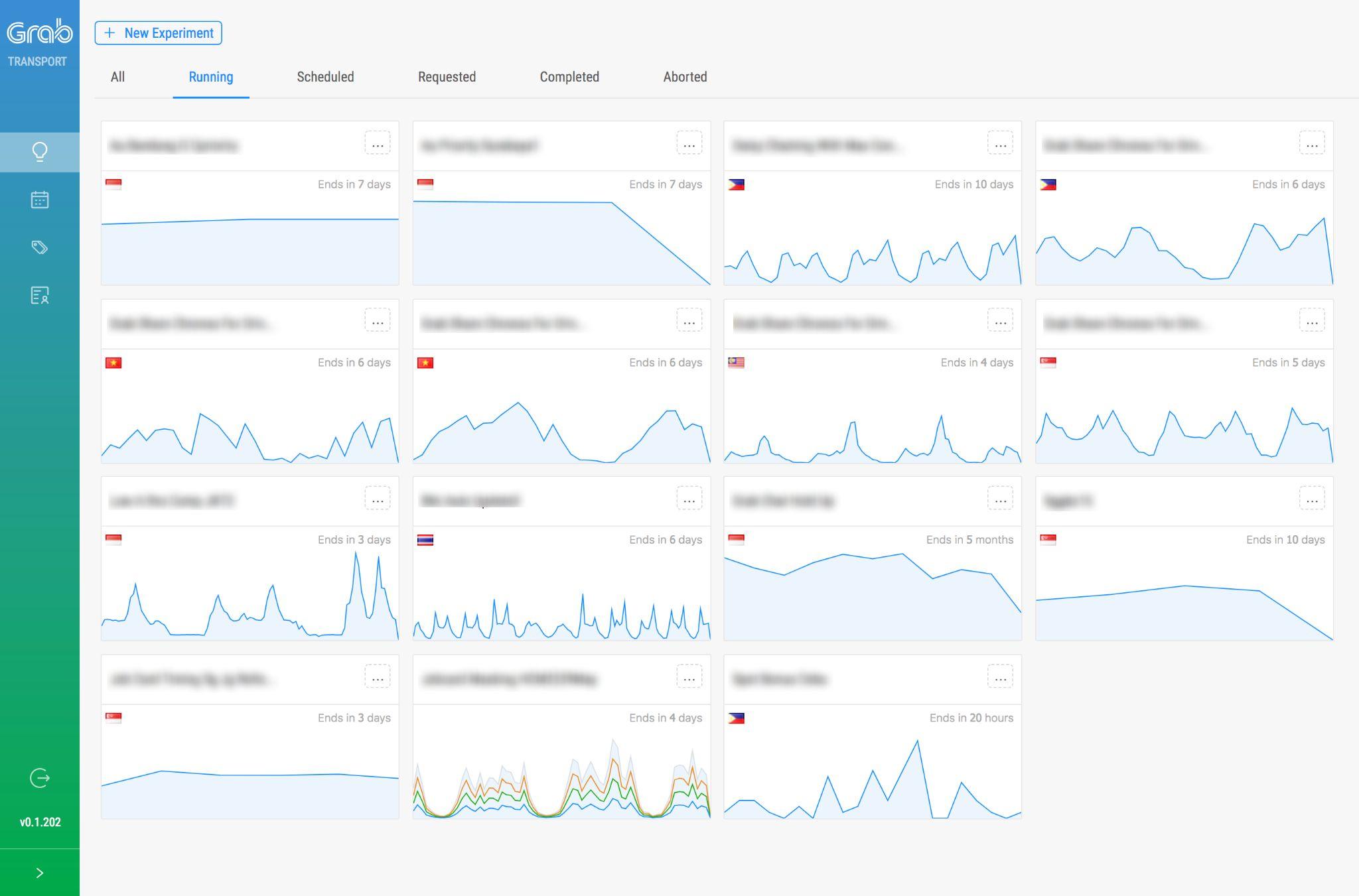

Figure: Experimentation Platform Portal

Figure: Experimentation Platform Portal

Why We Built ExP

In the early days, experiments were performed on a small scale that allowed users to define metrics, and then compute and surface those metrics for a small set of experiments. The process around experimentation was rather painful. When product managers wanted to run an experiment, they set up a meeting with product analysts, data scientists, and engineers. Experiments were designed, custom logging pipelines were built and services were modified to support each new experiment. It was an expensive and time-consuming process.

To overcome these challenges, we wanted to build a platform with the following goals in mind:

-

Create a unified experimentation platform across the organisation that prevents multiple concurrent experiments from interfering with one another and allows engineers and data scientists to work on the same set of tools.

-

Allow simple, fast, and cost-effective experiments

-

Automate the selection of representative cohorts of drivers and passengers to perform A/A testing.

-

Support power analysis to perform appropriate significance tests

-

Enable a fully automated data pipeline where experimental data is streamed out in real-time, then tagged and stored in S3

-

Create platform for plugging in custom analysis modules

-

Create Event Triggers/Alerts set up on important business metrics to identify adverse effects of a change

-

Design single centralised online UI for creating and managing the experiments, which is constantly being improved - long term vision is to allow anyone in the organization to create and run experiments

Since implementing ExP, we have seen the number of experiments grow from just a handful to about 25 running concurrently. More impressively, the number of metrics computed per day has grown exponentially to ~2500 distinct metrics per day and roughly 50,000 distinct experiment/metric combinations.

With this scale comes some issues we needed to address. Here is the architectural approach we have taken to address them:

Prevention of network effects - At Grab, we have several types of users: our driver-partners, passengers, and merchants. Unlike most experimentation platforms out there that deal with a single website visitor, our user types can and do interact with each other which leads to network effects in some cases. For example, an experiment on promotions can lead to a surge of demand more than the supply.

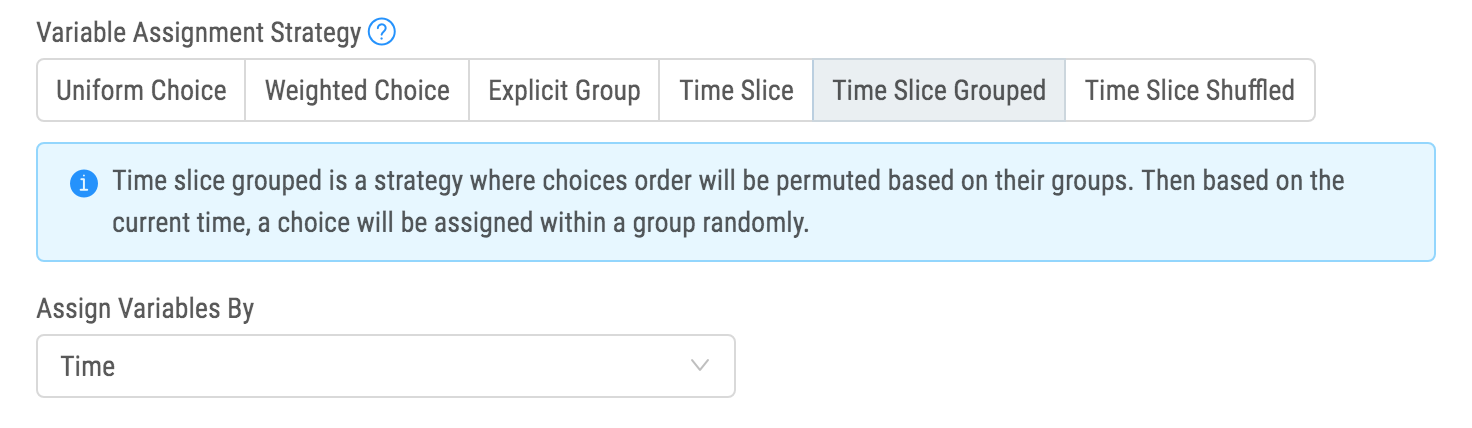

Control and treatment assignment strategies - Various teams within the organisation have different requirements and ways of setting up experiments. Some simple aesthetic experiments can be simply randomised by a user ID while other, algorithmic experiments may use a time-slicing strategies with bias minimisation. So we built many different strategies for different use-cases to address the challenging task of having all of these be both random and deterministic at the same time.

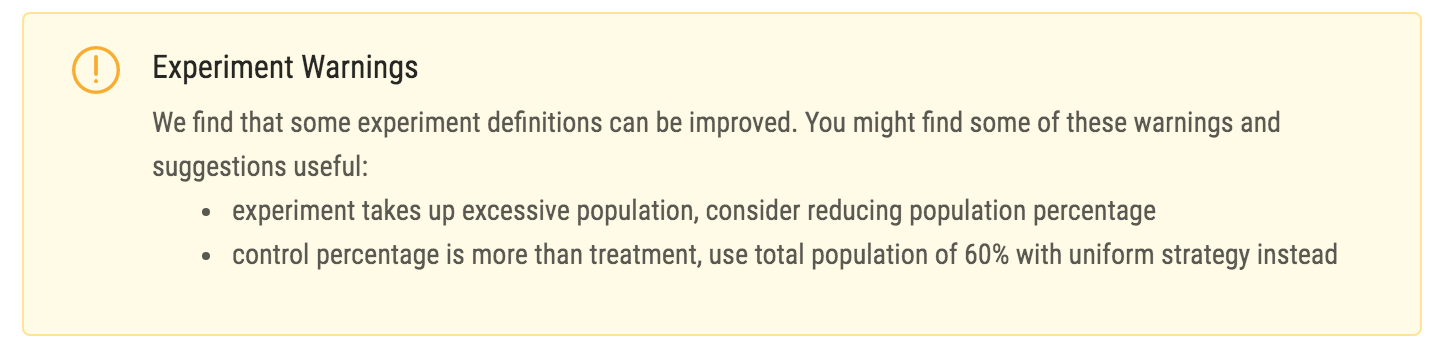

Prevention of experiment interference - We also attempt to gate for inter-experiment interference by providing a mechanism similar to Google’s Domains & Layers combined with an expert system for experiment design validation. We attempt to prevent interference of experiments by introducing a geo-temporal segmentation for concurrent experiments running together with advanced validation and suggestions to users on how experiments need to be setup.

Components of ExP

Grab’s ExP allows internal users (engineers, product managers, analysts, and others) to toggle various features on or off, adjust thresholds, change configurations dynamically without restarting anything. To achieve this, we’ve introduced a couple of cornerstone concepts in our UI and SDKs.

Variables and Metrics

The basic components of every experimentation platform are variables and metrics.

-

A Variable is something we can change, for example, different payment methods can be enabled for a particular user or a city.

-

A Metric is something we want to improve and keep observing. For example, cancellation rate or revenue. In our platform, we constantly keep track of metric changes.

Rollouts

Our rollout process consists of deploying a feature first to a small portion of users and then gradually ramping up in stages to larger groups. Eventually, we reach 100 percent of all users that fall under a target specification (for instance, geographic location, which can be as small as a district of a city.

The goal of a feature rollout is to make the deployment of new features as stable and reliable as possible by controlling user exposure in the early stages and monitoring the impact of the feature on key business metrics at each stage.

Groups

Our platform lets internal users define custom groups (also known segments). A group is a set of identifiers such as passenger IDs, geohashes, cities, and others. We use this to logically group a set of things that we can then conduct rollouts and experiments on.

Experiments

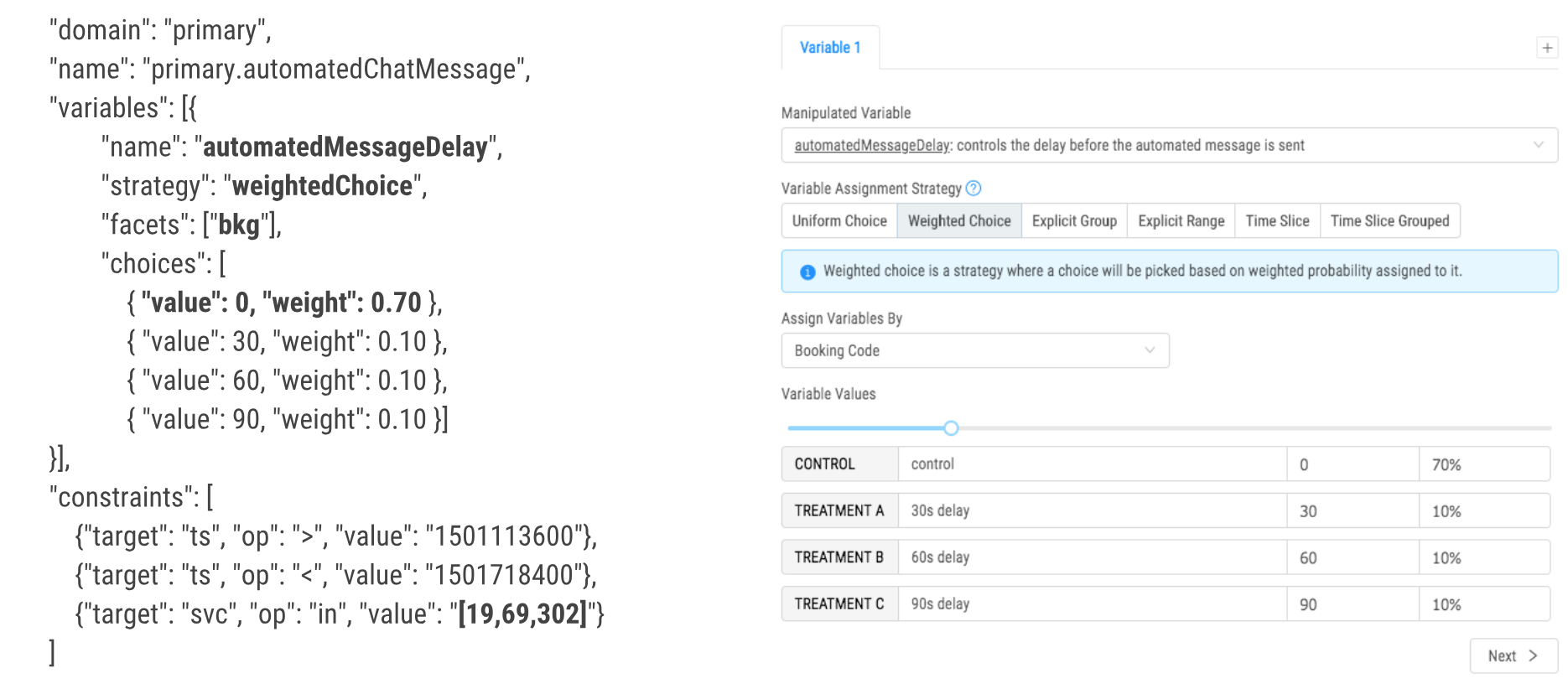

At Grab, we have formalised an “experiment definition” which is essentially a time-bound (with start and end time) configuration which can be split between control and treatment(s) for one or multiple variables. This configuration is stored as a JSON document and contains the entire experiment setup.

It is important to highlight that having a formal experiment definition actually brings several benefits to the table:

-

Machines can understand it and can automatically and autonomously execute experiments, even in distributed systems.

-

Communication between teams (engineering, product and data science) is simplified as formal documents to ensure everyone is on the same page.

Structured Experimental Design

With a formalised experiment definition, we then provide Android, iOS and Golang SDKs which consume experiment definitions and apply experiments.

Experiment definitions allow our SDKs to intelligently apply experiments without actually doing any costly network calls. Experiments get delivered to the SDKs through our configuration management platform, which supports dynamic reconfiguration.

Our SDKs implement various algorithms that enable experiment designers to set up experiments and define an assignment strategy (algorithm), which determines the value to be returned for a particular variable, and for a particular user.

Overall, we support two major and frequently used strategies:

-

Randomised sampling with uniform or weighted probability. This is useful when we want to randomly sample between control and treatment(s), for example, if we want 50% of passengers to get one value and 50% of passengers to get another value for the given variable.

-

Time-sliced experiments where control and treatment(s) are split by time (for example, 10 minutes control, then 10 minutes for treatment).

Sample Experiment

Since its rollout, ExP and its staged rollout framework have proven to be indispensable to many Grab feature deployments.

Take the GrabChat feature, for example. Booking cancellations were a key problem and the team believed that with the right interventions in place, some cancellations could be prevented.

One of the ideas we had was to use GrabChat to establish a conversation between the driver and the passenger by sending automated messages. This transforms the service from a mere transaction to something more human and personal. By adding this human touch to the service, it reduced perceived waiting time, making passengers and driver-partners more patient and accepting of any unavoidable delays that might arise.

When we deployed this new feature for app users in a specific geographic area, we noticed a drop in cancellations. To validate this, we conducted a series of iterative experiments using ExP. Check out this blog to find out more: https://engineering.grab.com/experiment-chat-booking-cancellations

Lastly, we used the platform to perform a staged rollout of this functionality to different users in different countries across Southeast Asia.

Conclusion

Building our own experimentation platform hasn’t been an easy process, but it has helped promote a culture of experimentation within the organisation. It has allowed data scientists and product teams to analyse the quality of new features and perform iterations more frequently, with our team working closely with them to support various assignment strategies and hypothesis.

Looking ahead, there is more we can do to evolve ExP. We’re looking at building automated and real-time dashboards and funnels with slice and dice functionality for our experiments and further increasing experimental capacity while maintaining strict boundaries in order to maintain validity of experiments. Ultimately, to keep improving, we must keep experimenting.