Engineering

Engineering

Democratising Fare Storage at Scale Using Event Sourcing

From humble beginnings, Grab has expanded across different markets in the last couple of years. We’ve added a wide range of features to the Grab platform to continue to delight our consumers and driver-partners. We had to incessantly find ways to improve our existing solutions to better support new features.

In this blog, we discuss how we built Fare Storage, Grab’s single source of truth fare data store, and how we overcame the challenges to make it more reliable and scalable to support our expanding features.

To set some context for this blog, let’s define some key terms before proceeding. A Fare is a dollar amount calculated to move someone or something from point A to point B. And, a Fee is a dollar amount added to or subtracted from the original fare amount for any additional service.

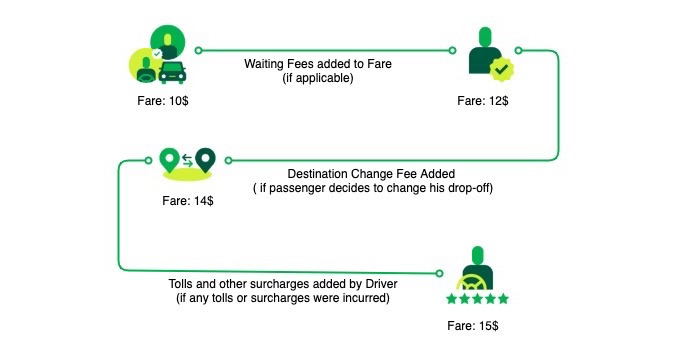

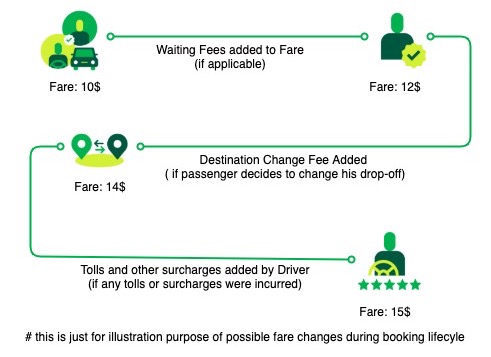

Now that you’re acquainted with the key concepts, let’s look take a look at the following image. It illustrates that features such as Destination Change Fee, Waiting Fee, Cancellation Fee, Tolls, Promos, Surcharges, and many others store additional fee breakdown along with the original fare. This set of information is crucial for generating receipts and debugging processes. However, our legacy storage system wasn’t designed to host massive quantities of information effectively.

In our legacy architecture, we stored all the booking and fare-related information in a single relational database table. Adding new fare fields and breakdowns required changes in our critical booking system, making iterations prohibitively expensive and hindering innovation.

The need to store the fare information and metadata for every additional feature along with other booking information resulted in a bloated booking entity. With millions of bookings created every day at Grab, this posed a scaling and stability threat to our booking service storage. Moreover, the legacy storage only tracked the latest value of fare and lacked a holistic view of all the modifications to the fare. So, debugging the fare was also a massive chore for our Engineering and Tech Operations teams.

Drafting a Solution

The shortcomings of our legacy system led us to explore options for decoupling the fare and its metadata storage from the booking details. We wanted to build a platform that can store and provide access to both fare and its audit trail.

High-level functional requirements for the new fare store were:

- Provide a platform to store and retrieve fare and associated breakdowns, with no tight coupling between services.

- Act as a single source-of-truth for fare and associated fees in the Grab ecosystem.

- Enable clients to access the metadata of fare change events in real-time, enabling the Product team to innovate freely.

- Provide smooth access to a fare’s audit trail, improving the response time to our consumers’ queries.

Non-functional requirements for the fare store were:

- High availability for the read and write APIs, with few milliseconds latency.

- Handle concurrent updates to the fare gracefully.

- Detect duplicate events for a booking for the same transaction.

Storing Change Sequence with Event Sourcing

Our legacy storage solution used a defined schema and only stored the latest state of the fare. We needed an audit trail-based storage system with fast querying capabilities that can store and retrieve changes in chronological order.

The Event Sourcing pattern stood out as a flexible architectural pattern as it allowed us to store and query the sequence of changes in the order it occurred. In Martin Fowler’s blog, he described Event Sourcing as:

“The fundamental idea of Event Sourcing is to ensure that every change to the state of an application is captured in an event object and that these event objects are themselves stored in the sequence they were applied for the same lifetime as the application state itself.”

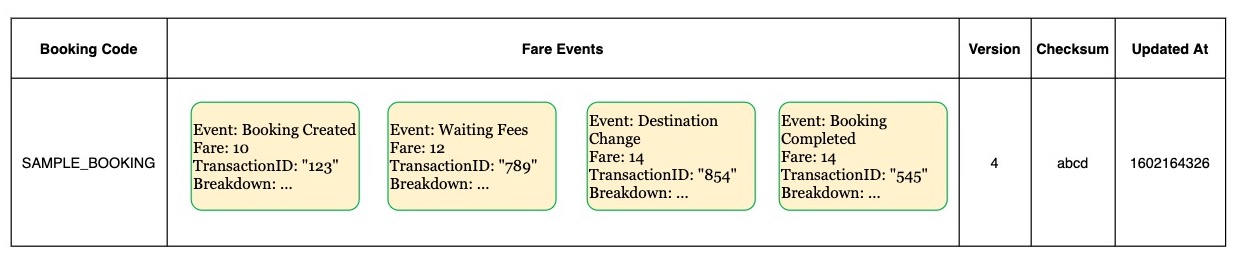

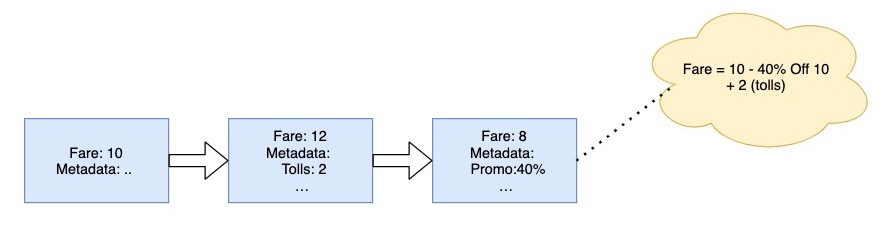

With the Event Sourcing pattern, we store all the fare changes as events in the order they occurred for a booking. We iterate through these events to retrieve a complete snapshot of the modifications to the fare.

A sample Fare Event looks like this:

message Event {

// type of the event, ADD, SUB, SET, resilient

EventType type = 1;

// value which was added, subtracted or modified

double value = 2;

// fare for the booking after applying discount

double fare = 3;

...

// description bytes generated by SDK

bytes description = 11;

//transactionID for the EventType

string transactionID = 12;

}

The Event Sourcing pattern also enable us to use the Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) pattern to decouple the read responsibility for different use cases.

Clients of the fare life cycle read the current fare and create events to change the fare value as per their logic. Clients can also access fare events, when required. This pattern enable clients to modify fares independently, and give them visibility to the sequence for different business needs.

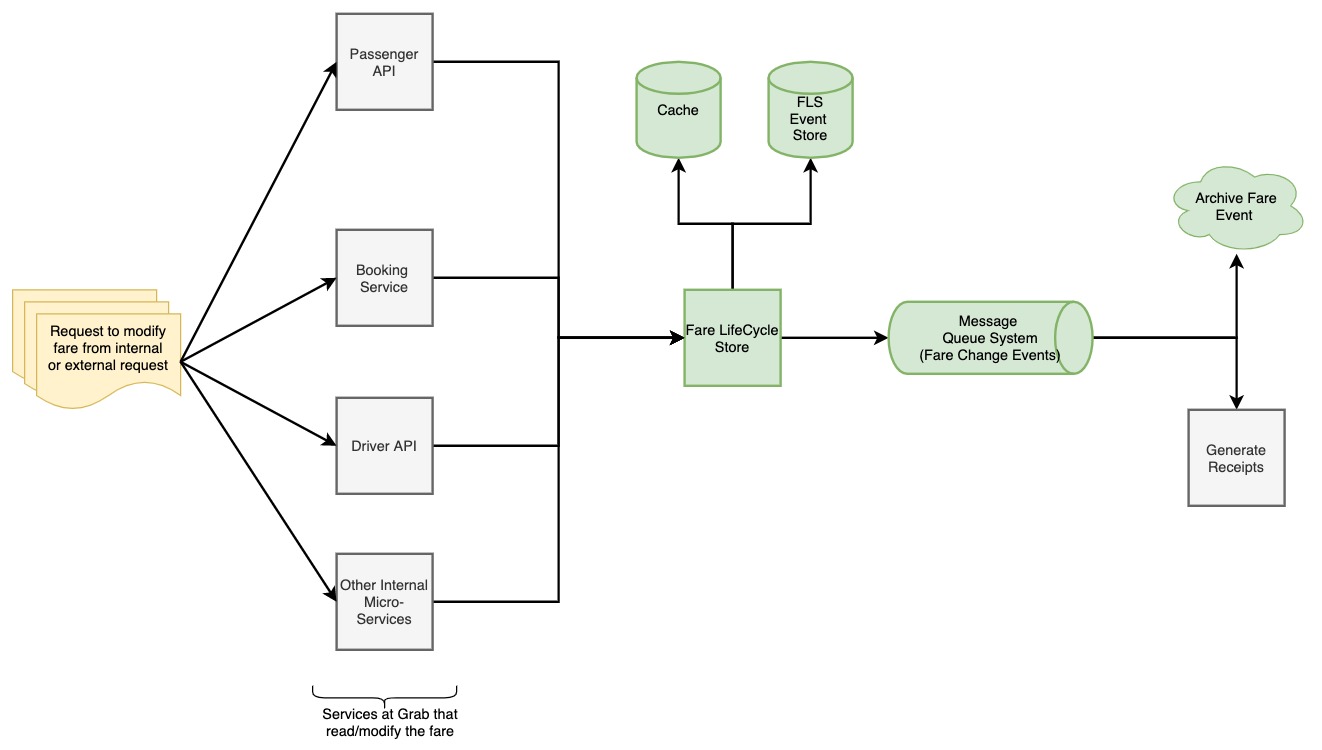

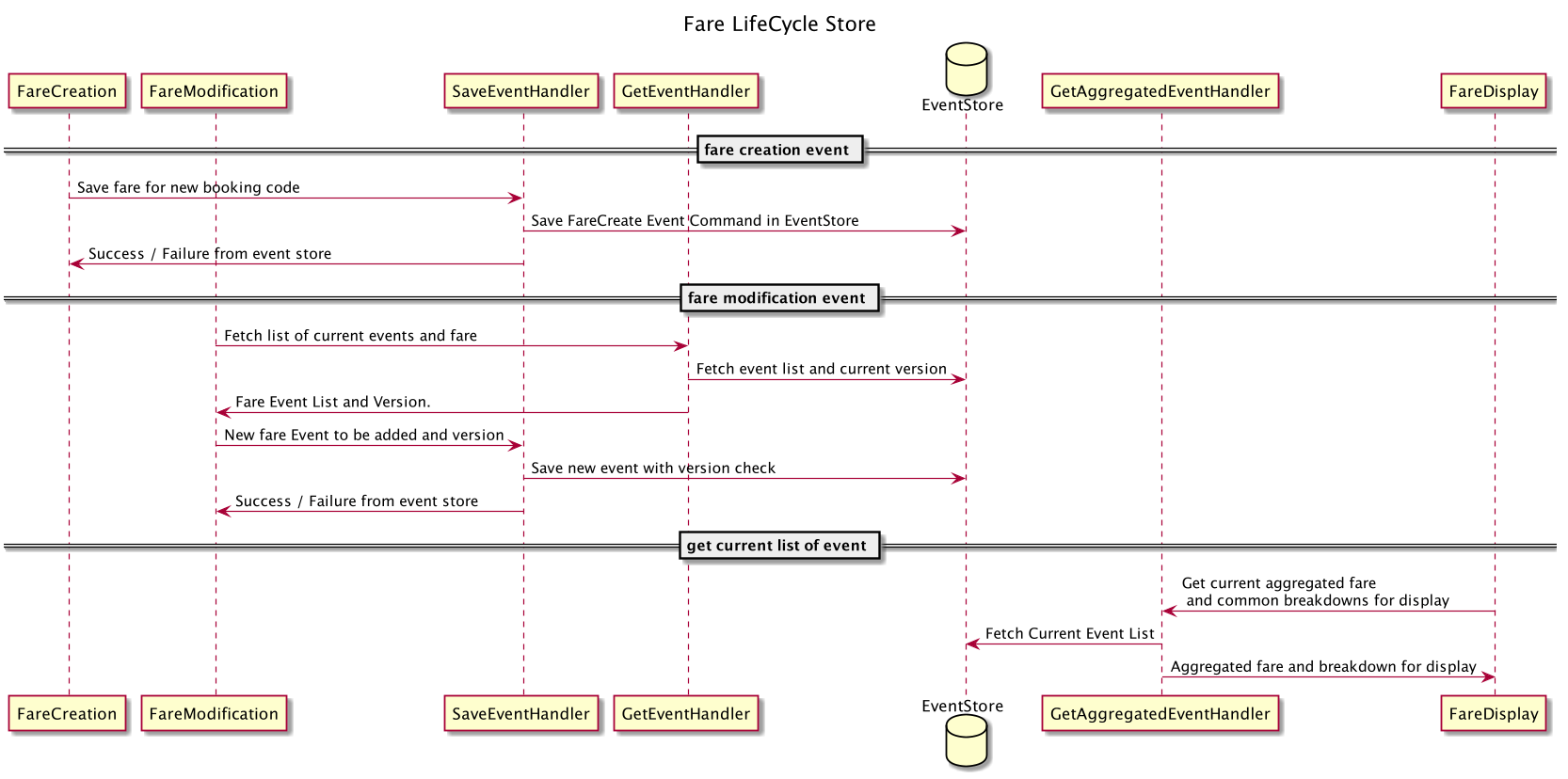

The diagram below describes the overall fare life cycle from creation, modification to display using the event store.

Architecture Overview

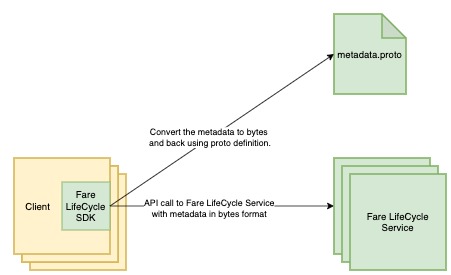

Clients interact with the Fare LifeCycle service through an SDK. The SDK offers various features such as metadata serialisation, deserialisation, retries, and timeouts configurations, some of which are discussed later.

The Fare LifeCycle Store service uses DynamoDB as Event Store to persist and read the fare change events backed by a cache for eventually consistent reads. For further processing, such as archiving and generation of receipts, the successfully updated events are streamed out to a message queue system.

Ensuring the Integrity of the Fare Sequence

Democratising the responsibility of fare modification means that multiple services might try to update the fare in parallel without prior synchronisation. Concurrent fare updates for the same booking might result in a race condition. Concurrency and consistency problems are always highlights of distributed storage systems.

Let’s understand why the ordering of fare updates are important. Business rules for different cities and countries regulate the pricing features based on local market conditions and prevailing laws. For example, in some scenarios, Tolls and Waiting Fees may not be eligible for discounts or promotions. The service applying discounts needs to consider this information while applying a discount. Therefore, updates to the fare are not independent of the previous fare events.

We needed a mechanism to detect race conditions and handle them appropriately to ensure the integrity of the fare. To handle race conditions based on our use case, we explored Pessimistic and Optimistic locking mechanisms.

All the expected fare change events happen based on certain conditions being true or false. For example, less than 1% of the bookings have a payment change request initiated by passengers during a ride. And, the probability of multiple similar changes happening on the same booking is rather low. Optimistic Locking offers both efficiency and correctness for our requirements where the chances of race conditions are low, and the records are independent of each other.

The logic to calculate the fare/surcharge is coupled with the business logic of the system that calculates the fare component or fees. So, handling data race conditions on the data store layer was not an acceptable option either. It made more sense to let the clients handle it and keep the storage system decoupled from the business logic to compute the fare.

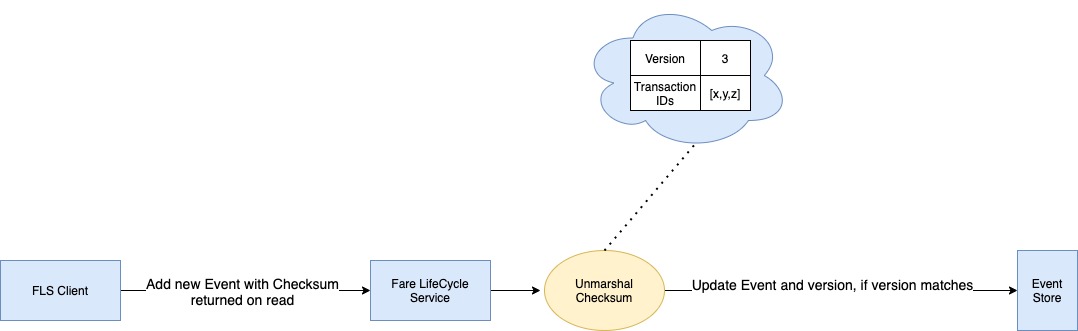

To achieve Optimistic Locking, we store a fare version and increment it on every successful update. The client must pass the version they read to modify the fare. Should there be a version mismatch between the update query and the current fare, the update is rejected. On version mismatches, the clients read the updated checksum(version) and retry with the recalculated fare.

Idempotency of Event Updates

The next challenge we came across was how to handle client retries - ensuring that we do not duplicate the same event for the booking. Clients might encounter sporadic errors as a result of network-related issues, although the update was successful. Under such circumstances, clients retry to update the same event, resulting in duplicate events. Duplicate events not only result in an extra space requirement, but it also impairs the clients’ understanding on whether we’ve taken an action multiple times on the fare.

As discussed in the previous section, retrying with the same version would fail due to the version mismatch. If the previous attempt successfully modified the fare, it would also update the version.

However, clients might not know if their update modified the version or if any other clients updated the data. Relying on clients to check for event duplication makes the client-side complex and leaves a chance of error if the clients do not handle it correctly.

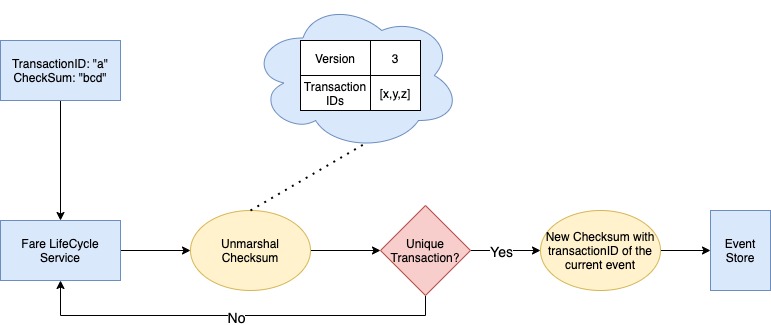

To handle the duplicate events, we associate each event with a unique UUID (transactionID) generated from the client-side using a UUID library from the Fare LifeCycle service SDK. We check whether the transactionID is already part of successful transaction IDs before updating the fare. If we identify a non-unique transactionID, we return duplicate event errors to the client.

For unique transactionIDs, we append it to the list of transactionIDs and save it to the Event Store along with the event.

Schema-less Metadata

Metadata are the breakdowns associated with the fare. We require the metadata for specific fee/fare calculation for the generation of receipts and debugging purposes. Thus, for the storage system and multiple clients, they need not know the metadata definition of all events.

One goal for our data store was to give our clients the flexibility to add new fields to existing metadata or to define new metadata without changing the API. We adopted an SDK-based approach for metadata, where clients interact with the Fare LifeCycle service via SDK. The SDK has the following responsibilities for metadata:

- Serialise the metadata into bytes before making an API call to the Fare LifeCycle service.

- Deserialise the bytes metadata returned from the Fare LifeCycle service into a Go struct for client access.

Serialising and deserialising the metadata on the client-side decoupled it from the Fare LifeCycle Store API. This helped teams update the metadata without deploying the storage service each time.

For reading the breakdown, the clients pass the metadata bytes to the SDK along with the Event Type, and then it converts them back into the corresponding proto schema. With this approach, clients can update the metadata without changing the Data Store Service.

Conclusion

The Fare LifeCycle service enabled us to revolutionise the fare storage at scale for Grab’s ecosystem of services. Further benefits realised with the system are:

- The feature agnostic platform helped us to reduce the time-to-market for our hyper-local features so that we can further outserve our consumers and driver-partners.

- Decoupling the fare information from the booking information also helped us to achieve a better separation of concerns between services.

- Improve the overall reliability and scalability of the Grab platform by decoupling fare and booking information, allowing them to scale independently of each other.

- Reduce unnecessary coupling between services to fetch fare related information and update fare.

- The audit-trail of fare changes in the chronological order reduced the time to debug fare and improved our response to consumers for fare-related queries.

We hope this post helped you to have a closer look at how we used the Event Source pattern for building a data store and how we handled a few caveats and challenges in the process.

Authored by Sourabh Suman on behalf of the Pricing team at Grab. Special thanks to Karthik Gandhi, Kurni Famili, ChandanKumar Agarwal, Adarsh Koyya, Niteesh Mehra, Sebastian Wong, Matthew Saw, Muhammad Muneer, and Vishal Sharma for their contributions.

Join us

Grab is a leading superapp in Southeast Asia, providing everyday services that matter to consumers. More than just a ride-hailing and food delivery app, Grab offers a wide range of on-demand services in the region, including mobility, food, package and grocery delivery services, mobile payments, and financial services across over 400 cities in eight countries.

Powered by technology and driven by heart, our mission is to drive Southeast Asia forward by creating economic empowerment for everyone. If this mission speaks to you, join our team today!