Engineering

Engineering

Designing Resilient Systems: Circuit Breakers or Retries? (Part 2)

This post is the second part of the series on Designing Resilient Systems. In Part 1, we looked at use cases for implementing circuit breakers. In this second part, we will do a deep dive on retries and its use cases, followed by a technical comparison of both approaches.

Introducing Retry

Retry is a software mechanism that monitors a request, and if it detects failure, automatically repeats the request.

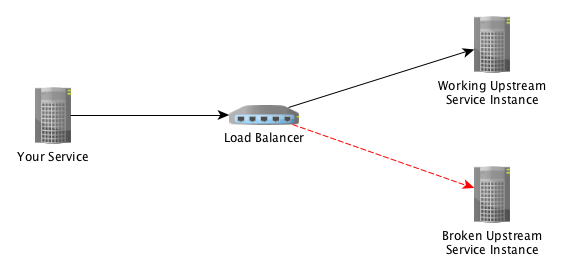

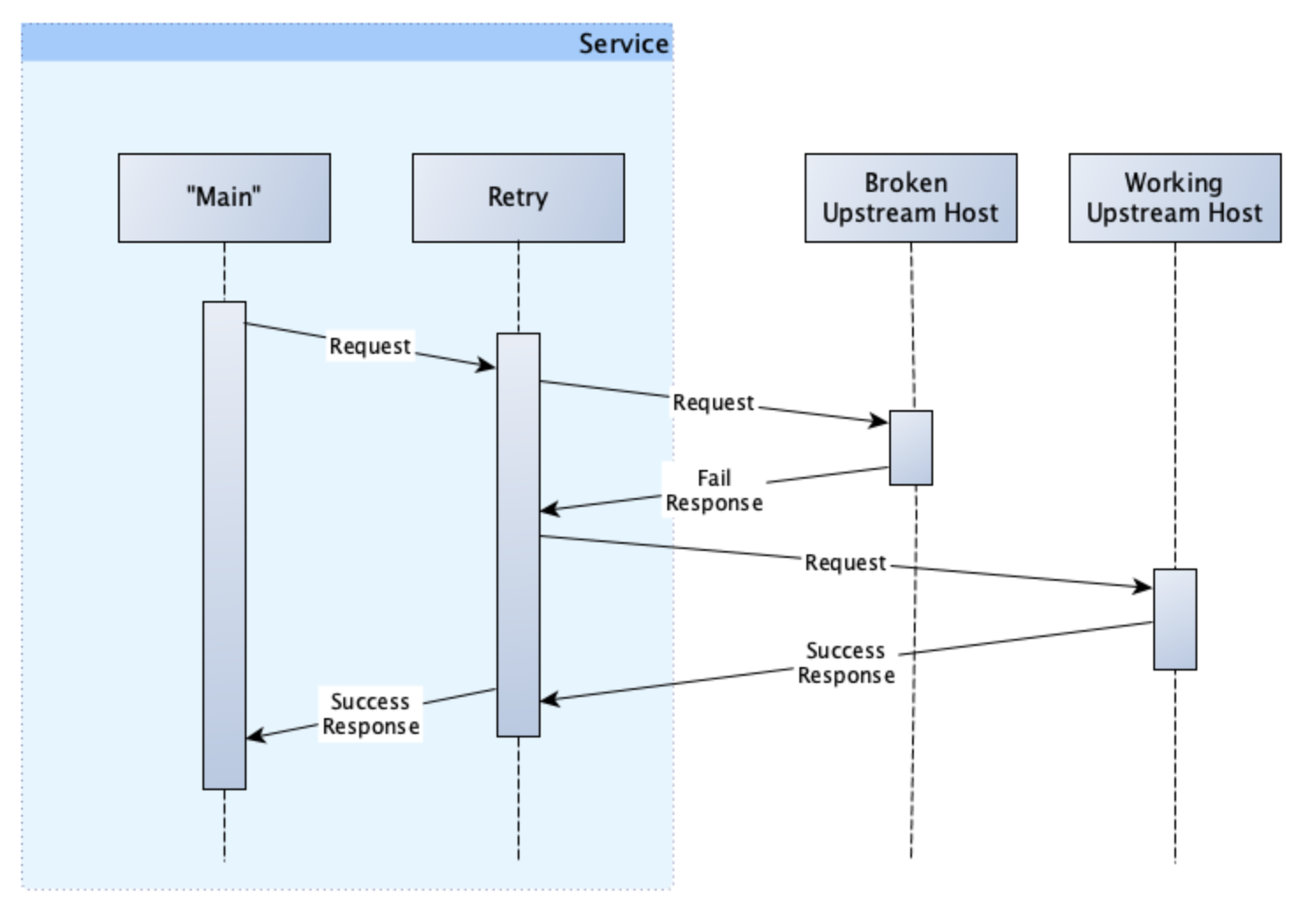

Let’s take the following example:

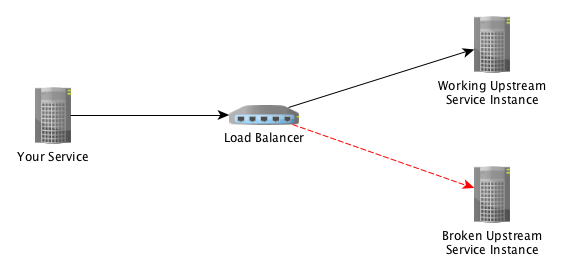

Assuming our load balancer is configured to perform round-robin load balancing, this means that with two hosts in our upstream service, the first request will go to one host and the second request will go to the other host.

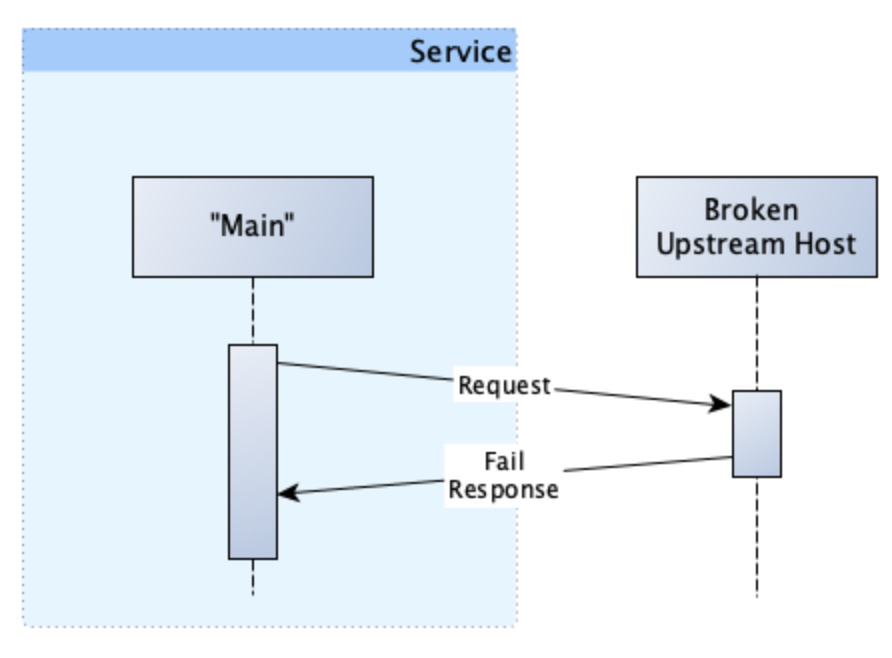

If our request was unlucky and we were routed to the broken host, then our interaction would look like this:

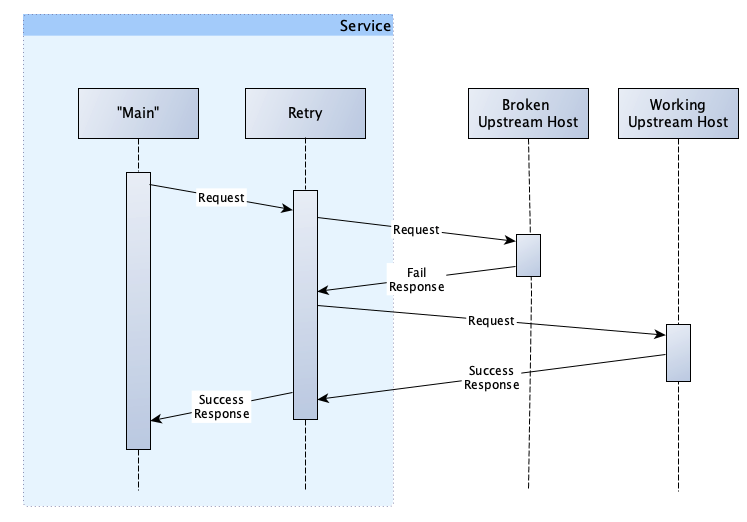

However, with retries in place, our interaction would look like this:

You’ll notice a few things here. Firstly, because of the retry, we have successfully completed our processing; meaning we are returning fewer errors to our users.

Secondly, while our request succeeded, it required more resources (CPU and time) to complete. We have to attempt the first request, wait for and detect the failure, before repeating and succeeding on our second attempt.

Lastly, unlike the circuit breaker (discussed in Part 1), we are not tracking the results of our requests. We are, therefore, not doing anything to prevent ourselves from making requests to the broken host in the future. Additionally, in our example, our second request was routed to the working host. This will not always be the case, given that there will be multiple concurrent requests from our service and potentially even requests from other services. As such, we are not guaranteed to get a working host on the second attempt. In fact, the chance for us to get a working host is equal to the number of working hosts divided by the total hosts, in this case 50%.

Digging a little deeper, we had a 50% chance to get a bad host on the first request, and a 50% chance on the retry. By extension we therefore have a 50% x 50% = 25% chance to fail even after 1 retry. If we were to retry twice, this becomes 12.5%.

Understanding this concept will help you determine your max retries setting.

Should We Retry for All Errors?

The short answer is no. We should consider retrying the request if it has any chance of succeeding (i.e. error codes 503 - Service Unavailable and 500 - Internal Server Error). For example, for error code 503, a retry may work if the retry resulted in a call to a host that was not overloaded. Conversely, for errors like 401 - Unauthorised or 400 - Bad Request, retrying these wastes resources as they will never work without the user changing their request.

There are two key points to consider: Firstly, the upstream service must return sensible and informative errors and secondly, our retry mechanism must be configured to react to different types of errors differently.

Idempotency

A process (function or request) is considered to be idempotent if it can be repeated any number of times (i.e. one or more) and have the same result.

Let’s say you have a REST endpoint that loads a city. Every time you call this method, you should receive the same outcome. Now, let’s say we have another endpoint, but this one reserves a ticket. If we call this endpoint twice, then we will have reserved 2 tickets. How does this relate to retries?

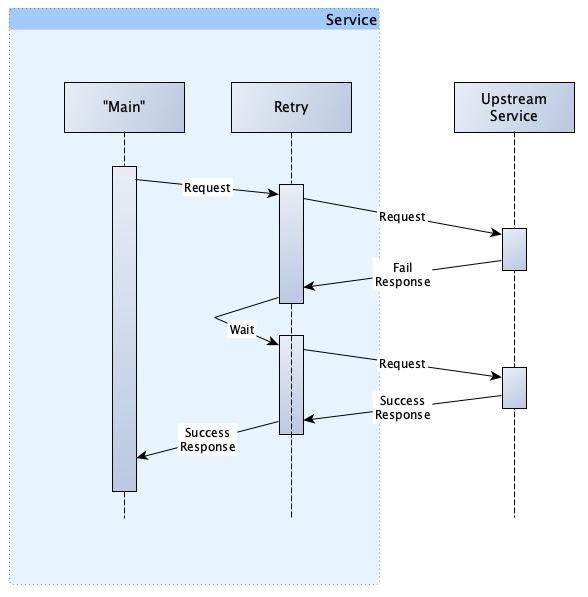

Examine our retry interaction from above again:

What happens if our first call to the broken host actually reserves at ticket but fails to respond to us correctly. Our retry to the second working host would then reserve a second ticket, and we would have no idea that we had made a mistake.

This is because our reserve a ticket endpoint is not idempotent.

Please do not take the above example to imply that only read operations can be retried and that all write/mutate changes cannot be; the example was chosen carefully.

A reserve a ticket operation is almost always going to involve some finite amount of tickets, and in such a situation it is imperative that 1 request only results in 1 reservation. Other similar situations might include charging a credit card or incrementing a counter.

Some write operations, like saving a registration or updating a record to a provided value (without calculation) can be repeated. Saving multiple registrations will cause messy data, but that can be cleaned up by some other non-consumer related process. In this case, it’s better to ensure we fulfil the consumers request at the expense of extra work for us rather than failing, leaving the system in an unknown state and making it the consumer’s problem. For example, let’s say we were updating the user’s password to abc123, this end state which was provided by the user is fixed and so, therefore, repeating the process only wastes the resources of the data store.

In cases where retries are possible, but you want to be able to detect and prevent duplicate transactions (like in our ticket reservation example) it is possible to introduce a cryptographic nonce. This topic would require an article all of its own, but the short version is: a cryptographic nonce is a random number introduced into a request that helps us detect that two requests are actually one.

If that didn’t make much sense, here’s an example:

Let’s say we receive a ticket registration request from our consumer, and we append to it a random number. Now, when we call our upstream service, we can pass the request data together with the nonce. This request is partially processed but then fails and returns an HTTP 500 - Internal Server Error. We retry this request with another upstream service host and again supply the request data and the exact same nonce. The upstream host is now able to use this nonce and other identifying information in the request (e.g. consumer id, amount, ticket type, etc.) to determine that both requests originate from the same user request and therefore should be treated as one. In our case, this might mean we return the tickets reserved by the first partially processed request and complete the processing.

For more information on cryptographic nonces, start here.

Backoff

In our previous example, when we failed, we immediately tried again and because the load balancer gave us a different host, the second request succeeded. However, this is not actually how it works. The actual implementation includes a delay/wait in-between request like this:

This amount of wait time between requests is called the backoff.

Consider what happens when all hosts of the upstream service are down. Remember, the upstream service could be just one host (like a database). If we were to retry immediately, we would have a high chance to fail again and again and again, until we exceeded our maximum number of attempts.

Viewed simply, the backoff is a process that changes the wait time between attempts based on the number of previous failures.

Going back to our example, let’s assume that our backoff delay is 100 milliseconds.

| Retry Attempt | Delay |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 x 100ms = 100ms |

| 2 | 2 x 100ms = 200ms |

| 5 | 5 x 100ms = 500ms |

| 10 | 10 x 100mx = 1,000ms |

The underlying theory here is that if a request has already failed a few times, then it has an increased likelihood of failing again. We, therefore, want to give the upstream service the greater chance to recover and be able to fulfil our request.

By increasing the delay, we are not only giving it more time to recover, but we are spreading out the load of our requests and retries. In cases where the request failure is caused by the upstream service being overloaded, this spreading out of the load also gives us a greater chance of success.

Jitter

With backoff in-place, we have a way to spread out the load we are sending to our upstream service. However, the load will still be spiky.

Let’s say we make 10,000 requests and they all fail because the upstream service cannot handle that amount of simultaneous requests. Following our simple backoff implementation from earlier, after 100ms delay we would retry all 10,000 requests which would also fail for the same reason. To avoid this, the retry implementation includes jitter. Jitter is the process of increasing or decreasing the delay from the standard to further spread out the load. In our example, this might mean that our 10,000 requests are delayed between 70-150ms (for the first retry attempt) by a random amount.

The goal here is similar to above, which is to smooth out the request load.

Note: For purposes of this article we’ve provided a vastly over-simplified definition of backoff and jitter. If you would like a more in-depth description, please read this article.

Settings

In Grab, we have implemented our own retry library inspired by this AWS blog article. In this library we have the following settings:

Maximum Retries

This value indicates how many times a request can be retried before giving up (failing).

Retry Filter

This is a function that processes the returned error and decides if the request should be retried.

Base and Max Delay

When we combine the concepts of backoff and jitter, we are left with these two settings.

The base delay is the minimum backoff delay between attempts, while the max delay is the maximum delay between attempts.

Note: The actual delay will always be between these the values for Base and Max Delays and will also be based on the attempt number (number of previous failures).

Time-boxing Requests

While the underlying goal of the retry mechanism is to do everything possible to fulfil our user’s request by retrying until we successfully complete the request, we cannot try forever.

At some point, we need to give up and allow the failure.

When configuring the retry mechanism, it is essential to tune the Maximum Retries, Request Timeout, and Maximum Delay together. The target to keep in mind when tuning these values is the worst-case response time to our consumer.

The worst-case response time can be calculated as: (maximum retries x request timeout) + (maximum retries x maximum delay)

For example:

| Max Retries | Request Timeout (ms) | Maximum Delay (ms) | Total Time for first attempt and retries | Total time for delays | Total Time Overall (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 100 | 200 | 3 x 100 | 2 x 200 | 800 |

| 5 | 100 | 200 | 6 x 100 | 5 x 200 | 1,600 |

| 3 | 500 | 200 | 4 x 500 | 3 x 200 | 2,600 |

You can see from this table how the total amount of time taken very quickly escalates.

Circuit Breakers vs Retries

Some of the original discussions that started this series was centred around one question “why use a circuit-breaker when you can just retry?” Let’s dig into this a little deeper.

Communication with Retries only

Assuming we take sufficient time to plan, track and tune our retry settings, a system that only has retries will have an excellent chance of successfully achieving our goals by merely retrying.

Consider our earlier example:

In this simple example, setting our retry count to 1 would ensure that we would achieve our goals. If the first attempt went to the broken host, we would merely retry and be load-balanced to the other working host.

Sounds good right? So where is the downside? Let’s consider a failure scenario where our broken host does not throw an error immediately but instead never responds. This means:

- When routed to the working host first then the response time would be fast, whatever the processing time of the working host is.

- When routed to the broken host first then the response time would be equal to our Request Timeout setting plus the processing time of the working host.

As you can imagine, if we had more hosts and in particular more broken hosts, then we would require a higher setting for Maximum Retries, and this would result in higher potential response time (i.e. multiples of the Request Timeout setting).

Now consider the worst-case scenario - when all the upstream hosts are down. All of our requests will take at least Maximum Retries x Request Timeout to complete. This situation is referred to as cascading failure (more info).

Another form of cascading failure occurs when the load that should be handled by a broken host is added to a working host, causing the working host to become overloaded.

For example, if in our above example, we have 2 hosts that are capable of handling 10k requests/second each. If we currently have 15k requests/second, then our load balancer has spread the load, and we have 7.5k requests/second on each.

However, because all requests to the broken host are retried on the working host, our working host suddenly has to handle its original 7.5k requests plus 7.5k retries giving it 15k requests/second to handle, which it cannot.

Communication with Circuit Breaker Only

But what if you only implemented a circuit breaker and no retries? There are two factors to note in this scenario. Firstly, the error rate of our system is the error rate that is seen by our users. For example, if our system has a 10% error rate then 10% of our users would receive an error.

Secondly, should our error rate exceed the Error Percent Threshold then the circuit would open, and then 100% of our users would get an error even though there are hosts that could successfully process the request.

Circuit Breaker and Retries

The third option is of course to adopt both circuit breaker and retry mechanisms.

Taking the same example we used in the previous section, if we were to retry the 10% of requests that failed once, 90% of those requests would pass on the second attempt. Our success rate would then go from the original 90% to 90% + ( 90% x 10%) = 99%

Perhaps another interesting side-effect of retrying and successfully completing the request is the effect that it has on the circuit itself. In our example, our error rate has moved from 10% to 1%. This significant reduction in our error rate means that our circuit is far less likely to open and prevent all requests.

Circuit Breaker Inside Retries / Retries Inside Circuit Breaker

It might seem strange but it is imperative that you spend some time considering the order in which you place the mechanisms.

For example, when you have the retry mechanism inside the circuit breaker, then when the circuit breaker sees a failure, this means that we have already attempted retries several times and still failed. An error in this situation should be rather unlikely. By extension then we should consider using a very low Error Percent Threshold as the trigger to open the circuit.

On the other hand, when we have a circuit breaker inside a retry mechanism, then when the retry mechanism sees a failure, this means either the circuit is open, or we have failed an individual request. In this configuration, the circuit breaker is monitoring all of the individual requests instead of the batch in the previous. As such, errors are going to be much more frequent. We, therefore, should consider a high Error Percent Threshold before opening the circuit. This configuration is also the only way to achieve circuit breaker per host.

The second configuration is by far my preferred option. I prefer it because:

- The circuit breaker is monitoring all requests.

- The circuit is not unduly influenced by one bad request. For example, a request with a large payload might fail when sent to all hosts, but all other requests are fine. If we have a low Error Percent Threshold setting, this might unduly influence the circuit.

- I like to ensure that bulwark inside our circuit breaker implementation also protects the upstream service from excessive requests, which it does more effectively when tracking individual requests

- If I set the Timeout setting on my circuit to some huge number (e.g. 1 hour), then I can effectively ignore it and the calculation of my maximum possible time spent calling the upstream service is simplified to (maximum retries x request timeout) + (maximum retries x maximum delay). Yes, this is not so simple, but it is one less setting to worry about.

Final Thoughts

In this two-part series, we have introduced two beneficial software mechanisms that can increase the reliability of our communications with external upstream services.

We have discussed how they work, how to configure them, and some of the less obvious issues that we must consider when using them.

While it is possible to use them separately, for me, it should never be a question of if you should have a circuit breaker or a retry mechanism. Where possible you should always have both. With the bulwark thrown in for free in our circuit breaker implementation, it gets even better.

The only thing that could make working with an upstream service even better for me, (e.g. more reliable and potentially faster) would be to add a cache in front of it all. But we’ll save that for another article.

I hope you have enjoyed this series and found it useful. Comments, corrections, and even considered disagreements are always welcome.

Happy Coding!