Engineering

Engineering

How We Implemented Domain-Driven Development in Golang

Partnerships have always been core to Grab’s superapp strategy. We believe in collaborating with partners who are the best in what they do - combining their expertise with what we’re good at so that we can bring high-quality new services to our consumers, at the same time create new opportunities for the merchant and driver-partners in our ecosystem.

That’s why we launched GrabPlatform last year. To make it easier for partners to either integrate Grab into their services, or integrate their services into Grab.

In view of that, part of the GrabPlatform’s team mission is to make it easy for partners to integrate with Grab services. These partners are external companies that would like to offer Grab’s services such as ride-booking through their own websites or applications. To do that, we decided to build a website that will serve as a one-stop-shop that would allow them to self-service these integrations.

The Challenges We Faced with the Conventional Approach

In the process of building this website, our team noticed that the majority of the functions and responsibilities were added to files without proper segregation. A single file would contain more than 500 lines of code. Each of these files were imported from different collections of source codes, resulting in an unstructured codebase. Any changes to the existing functions risked breaking existing functionality; we realised then that we needed to proactively plan for the future. Hence, we decided to use the principles of Domain-Driven Design (DDD) and idiomatic Go. This blog aims to demonstrate the process of how we leveraged those concepts to design a modern application.

How We Implemented DDD in Our Codebase

Here’s how we went about solving our unstructured codebase using DDD principles.

Step 1: Gather Domain (Business) Knowledge

We collaborated closely with our domain experts (in our case, this was our product team) to identify functionality and flow. From them, we discovered the following key points:

- After creating a project, developers are added to the project.

- The domain experts wanted an ability to add other products (e.g. Pricing service, ETA service, GrabPay service) to their projects.

- They wanted the ability to create multiple authentication clients to access the above products.

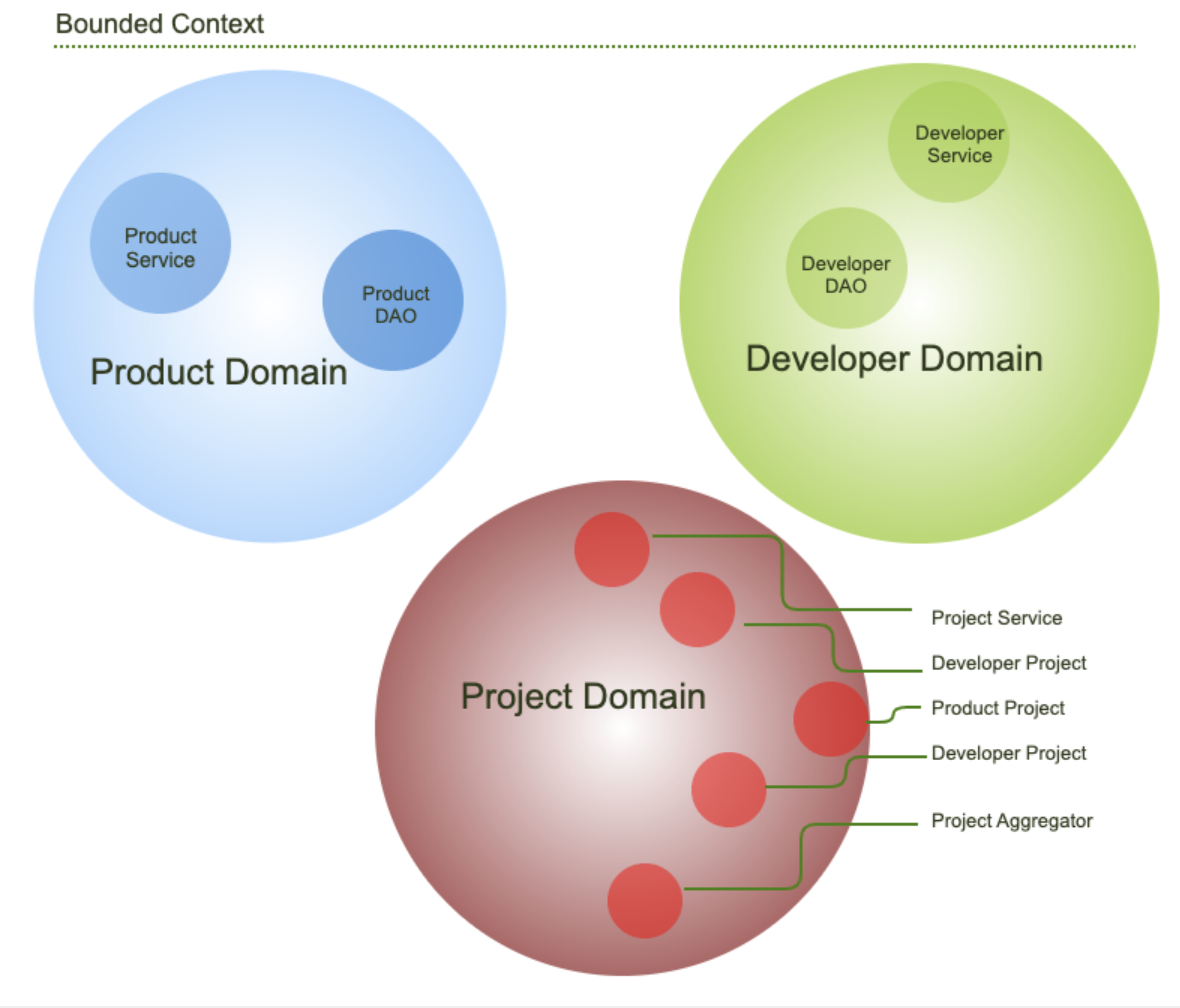

Step 2: Break Down Domain Knowledge into Bounded Context

Now that we had gathered the required domain knowledge (i.e. what our code needed to reflect to our partners), it was time to use the DDD strategic tool Bounded Context to break down problems into subcontexts. Here is a graphical representation of how we converted the problem into smaller units.

We identified several dependencies on each of the units involved in the project. Take some of these examples:

- The project domain overlapped with the product and developer domains.

- Our RideBooking project can only exist if it has some products like Ridebooking APIs and not the other way around.

What this means is a product can exist independent of the project, but a project will have no significance without any product. In the same way, a project is dependent on the developers, but developers can exist whether or not they belong to a project.

Step 3: Identify Value Objects or Entities (Lowest Layer)

Looking at the above bounded contexts, we figured out the building blocks (i.e. value objects or entity) to break down the above functionality and flow.

// ProjectDAO ...

type ProjectDAO struct {

ID int64

UUID string

Status ProjectStatus

CreatedAt time.Time

}

// DeveloperDAO ...

type DeveloperDAO struct {

ID int64

UUID string

PhoneHash *string

Status Status

CreatedAt time.Time

}

// ProductDAO ...

type ProductDAO struct {

ID int64

UUID string

Name string

Description *string

Status ProductStatus

CreatedAt time.Time

}

// DeveloperProjectDAO to map developer's to a project

type DeveloperProjectDAO struct {

ID int64

DeveloperID int64

ProjectID int64

Status DeveloperProjectStatus

}

// ProductProjectDAO to map product's to a project

type ProductProjectDAO struct {

ID int64

ProjectID int64

ProductID int64

Status ProjectProductStatus

}

All the objects shown above have ID as a field and can be identifiable, hence they are identified as entities and not as value objects. But if we apply domain knowledge, DeveloperProjectDAO and ProductProjectDAO are actually not independent entities. Project object is the aggregate root since it must exist before the child fields, DevProjectDAO and ProdcutProjectDAO, can exist.

Step 4: Create the Repositories

As stated above, we created an interface to abstract the working logic of a particular domain (i.e. Repository). Here is an example of how we designed the repositories:

// ProductRepositoryImpl responsible for product functionality

type ProductRepositoryImpl struct {

productDao storage.IProductDao // private field

}

type ProductRepository interface {

GetProductsByIDs(ctx context.Context, ids []int64) ([]IProduct, error)

}

// DeveloperRepositoryImpl

type DeveloperRepositoryImpl struct {

developerDAO storage.IDeveloperDao // private field

}

type DeveloperRepository interface {

FindActiveAllowedByDeveloperIDs(ctx context.Context, developerIDs []interface{}) ([]*Developer, error)

GetDeveloperDetailByProfile(ctx context.Context, developerProfile *appdto.DeveloperProfile) (IDeveloper, error)

}

Here is a look at how we designed our repository for aggregate root project:

// Unexported Struct

type productProjectRepositoryImpl struct {

productProjectDAO storage.IProjectProductDao // private field

}

type ProductProjectRepository interface {

GetAllProjectProductByProjectID(ctx context.Context, projectID int64) ([]*ProjectProduct, error)

}

// Unexported Struct

type developerProjectRepositoryImpl struct {

developerProjectDAO storage.IDeveloperProjectDao // private field

}

type DeveloperProjectRepository interface {

GetDevelopersByProjectIDs(ctx context.Context, projectIDs []interface{}) ([]*DeveloperProject, error)

UpdateMappingWithRole(ctx context.Context, developer IDeveloper, project IProject, role string) (*DeveloperProject, error)

}

// Unexported Struct

type projectRepositoryImpl struct {

projectDao storage.IProjectDao // private field

}

type ProjectRepository interface {

GetProjectsByIDs(ctx context.Context, projectIDs []interface{}) ([]*Project, error)

GetActiveProjectByUUID(ctx context.Context, uuid string) (IProject, error)

GetProjectByUUID(ctx context.Context, uuid string) (*Project, error)

}

type ProjectAggregatorImpl struct {

projectRepositoryImpl // private field

developerProjectRepositoryImpl // private field

productProjectRepositoryImpl // private field

}

type ProjectAggregator interface {

GetProjects(ctx context.Context) ([]*dto.Project, error)

AddDeveloper(ctx context.Context, request *appdto.AddDeveloperRequest) (*appdto.AddDeveloperResponse, error)

GetProjectWithProducts(ctx context.Context, uuid string) (IProject, error)

}

Step 5: Identify Domain Events

The functions described in Step 4 only returns the ID of the developer and product, which conveys no information to the users. In order to provide developer and product information, we use the domain-event technique to return the actual product and developer attributes.

A domain event is something that happened in a bounded context that you want another context of a domain to be aware of. For example, if there are new updates to the developer domain, it’s important to convey these updates to the project domain. This propagation technique is termed as domain event. Domain events enable independence between different classes.

One way to implement it is seen here:

// file: project\_aggregator.go

func (p *ProjectAggregatorImpl) GetProjects(ctx context.Context) ([]*dto.Project, error) {

....

....

developers := p.EventHandler.Handle(DomainEvent.FindDeveloperByDeveloperIDs{DeveloperIDs})

....

}

// file: event\_type.go

type FindDeveloperByDeveloperIDs struct{ developerID []interface{} }

// file: event\_handler.go

func (e *EventHandler) Handle(event interface{}) interface{} {

switch op := event.(type) {

case FindDeveloperByDeveloperIDs:

developers, _ := e.developerRepository.FindDeveloperByDeveloperIDs(op.developerIDs)

return developers

case ....

....

}

}

Some Common Mistakes to Avoid When Implementing DDD in Your Codebase

- Not engaging with domain experts. Not interacting with domain experts is a common mistake when using DDD. Talking to domain experts to get an understanding of the problem domain from their perspective is at the core of DDD. Starting with schemas or data modelling instead of talking to domain experts may create code based on a relational model instead of it built around a domain model.

- Ignoring the language of the domain experts. Creating a ubiquitous language shared with domain experts is also a core DDD practice. This common language must be used in all discussions as well as in the code, e.g. in class and method names.

- Not identifying bounded contexts. A common approach to solving a complex problem is breaking it down into smaller parts. Creating bounded contexts is breaking down a large domain into smaller ones, each handling one cohesive part of the domain.

- Using an anaemic domain model. This is a common sign that a team is not doing DDD and often a symptom of a failure in the modelling process. At first, an anaemic domain model often looks like a real domain model with correct names, but the classes lack functionalities. They contain only the

GetandSetmethods.

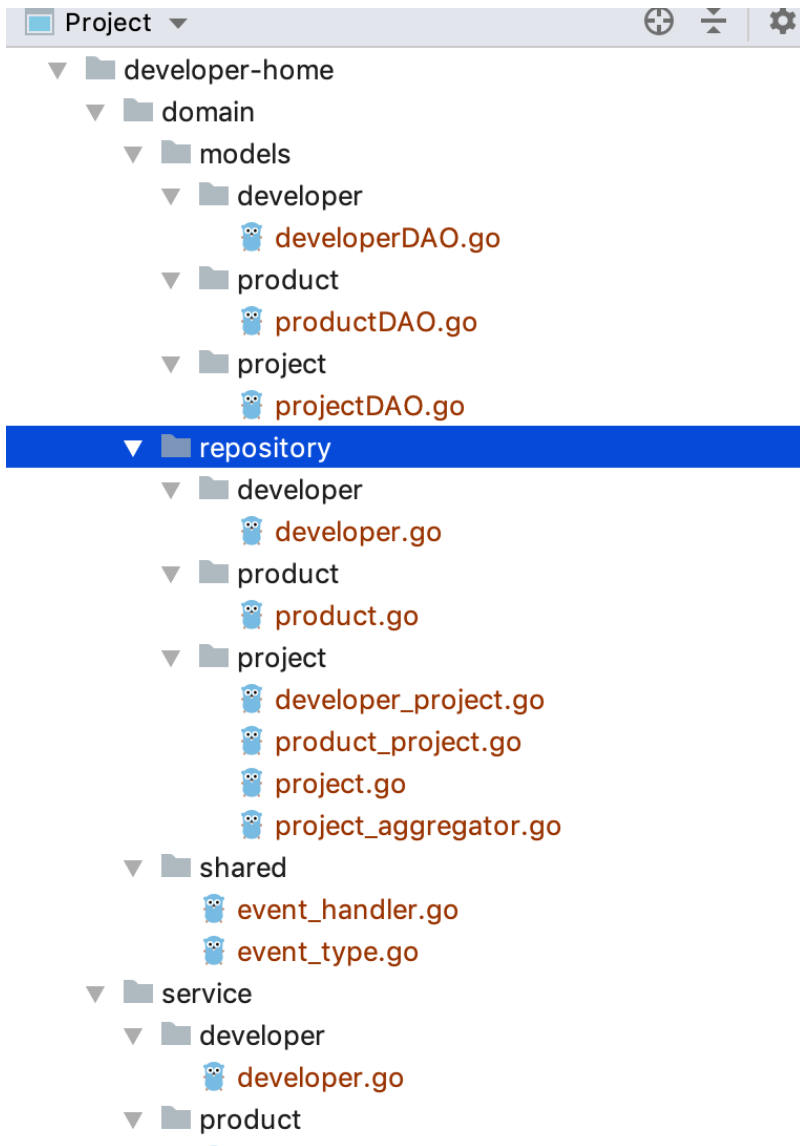

How the DDD Model Improved Our Software Development

Thanks to this brand new clean up, we achieved the following:

- Core functionalities are evenly distributed to the overall codebase and not limited to just a few files.

- The developers are aware of what each folder is responsible for by simply looking at the file naming and folder structure.

- The risk of breaking major functionalities by merely making small changes is greatly reduced. Changing a feature is now more efficient.

The team now finds the code well structured and we require less hand-holding for onboarders, thanks to the simplicity of the structure.

Finally, the most important thing, we now have a system oriented towards our business necessities. Everyone ends up using the same language and terms. Developers communicate better with the business team. The work is more efficient when it comes to establishing solutions for the models that reflect how the business operates, instead of how the software operates.

Lessons Learnt

- Use DDD to collaborate among all project disciplines (product, business, partner, and so on) and clearly understand the business requirements.

- Establish a ubiquitous language to discuss domain-related concepts.

- Use bounded contexts to break down complex domains into manageable parts.

- Implement a layered architecture (i.e. DDD building blocks) to focus on particular aspects of the application.

- To simplify your dependency, use domain event to communicate with sub-bounded context.