Engineering

·

Security

·

Data Science

Engineering

·

Security

·

Data Science

How facial recognition technology keeps you safe

Facial recognition technology is one of the many modern technologies that previously only appeared in science fiction movies. The roots of this technology can be traced back to the 1960s and have since grown dramatically due to the rise of deep learning techniques and accelerated digital transformation in recent years.

In this blog post, we will talk about the various applications of facial recognition technology in Grab, as well as provide details of the technical components that build up this technology.

Application of facial recognition technology

At Grab, we believe in prevention, protection, and action to create a safer every day for our consumers, partners, and the community as a whole. All selfies collected by Grab are handled according to Grab’s Privacy Policy and securely protected under privacy legislation in the countries in which we operate. We will elaborate in detail in a section further below.

One key incident prevention method is to verify the identity of both our consumers and partners:

- From the perspective of protecting the safety of passengers, having a reliable driver authentication process can avoid unauthorized people from delivering a ride. This ensures that trips on Grab are only completed by registered licensed driver-partners that have passed our comprehensive background checks.

- From the perspective of protecting the safety of driver-partners, verifying the identity of new passengers using facial recognition technology helps to deter crimes targeting our driver-partners and make incident investigations easier.

|

|

Facial recognition technology is also leveraged to improve Grab digital financial services, particularly in facilitating the “electronic Know Your Customer” (e-KYC) process. KYC is a standard regulatory requirement in the financial services industry to verify the identity of customers, which commonly serves to deter financial crime, such as money laundering.

Traditionally, customers are required to visit a physical counter to verify their government-issued ID as proof of identity. Today, with the widespread use of mobile devices, coupled with the maturity of facial recognition technologies, the process has become much more seamless and can be done entirely digitally.

Overview of facial recognition technology

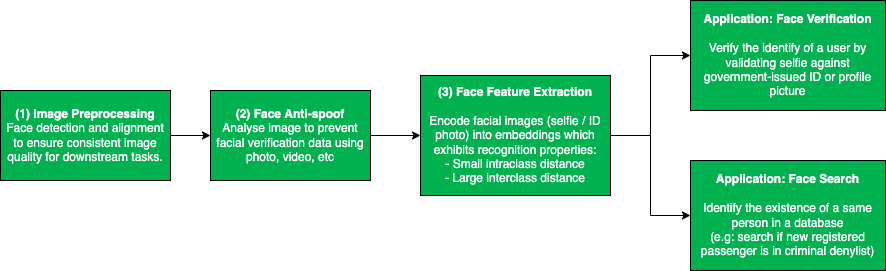

The typical facial recognition pipeline involves multiple stages, which starts with image preprocessing, face anti-spoof, followed by feature extraction, and finally the downstream applications - face verification or face search.

The most common image preprocessing techniques for face recognition tasks are face detection and face alignment. The face detection algorithm locates the face region in an image, and is usually followed by face alignment, which identifies the key facial landmarks (e.g. left eye, right eye, nose, etc.) and transforms them into a standardised coordinate space. Both of these preprocessing steps aim to ensure a consistent quality of input data for downstream applications.

Face anti-spoof refers to the process of ensuring that the user-submitted facial image is legitimate. This is to prevent fraudulent users from stealing identities (impersonating someone else by using a printed photo or replaying videos from mobile screens) or hiding identities (e.g. wearing a mask). The main approach here is to extract low-level spoofing cues, such as the moiré pattern, using various machine learning techniques to determine whether the image is spoofed.

After passing the anti-spoof checks, the user-submitted images are sent for face feature extraction, where important features that can be used to distinguish one person from another are extracted. Ideally, we want the feature extraction model to produce embeddings (i.e. high-dimensional vectors) with small intra-class distance (i.e. faces of the same person) and large inter-class distance (i.e. faces of different people), so that the aforementioned downstream applications (i.e. face verification and face search) become a straightforward task - thresholding the distance between embeddings.

Face verification is one of the key applications of facial recognition and it answers the question, “Is this the same person?”. As previously alluded to, this can be achieved by comparing the distance between embeddings generated from a template image (e.g. government-issued ID or profile picture) and a query image submitted by the user. A short distance indicates that both images belong to the same person, whereas a large distance indicates that these images are taken from different people.

Face search, on the other hand, tackles the question, “Who is this person?”, which can be framed as a vector/embedding similarity search problem. Image embeddings belonging to the same person would be highly similar, thus ranked higher, in search results. This is particularly useful for deterring criminals from re-onboarding to our platform by blocking new selfies that match a criminal profile in our criminal denylist database.

Face anti-spoof

For face anti-spoof, the most common methods used to attack the facial recognition system are screen replay and printed paper. To distinguish these spoof attacks from genuine faces, we need to solve two main challenges.

The first challenge is to obtain enough data of spoof attacks to enable the training of models. The second challenge is to carefully train the model to focus on the subtle differences between spoofed and genuine cases instead of overfitting to other background information.

Collecting large volumes of spoof data is naturally hard since spoof cases in product flows are very rare. To overcome this problem, one option is to synthesise large volumes of spoof data instead of collecting the real spoof data. More specifically, we synthesise moiré patterns on genuine face images that we have, and use the synthetic data as the screen replay attack data. This allows our model to use small amounts of real spoof data and sufficiently identify spoofing, while collecting more data to train the model.

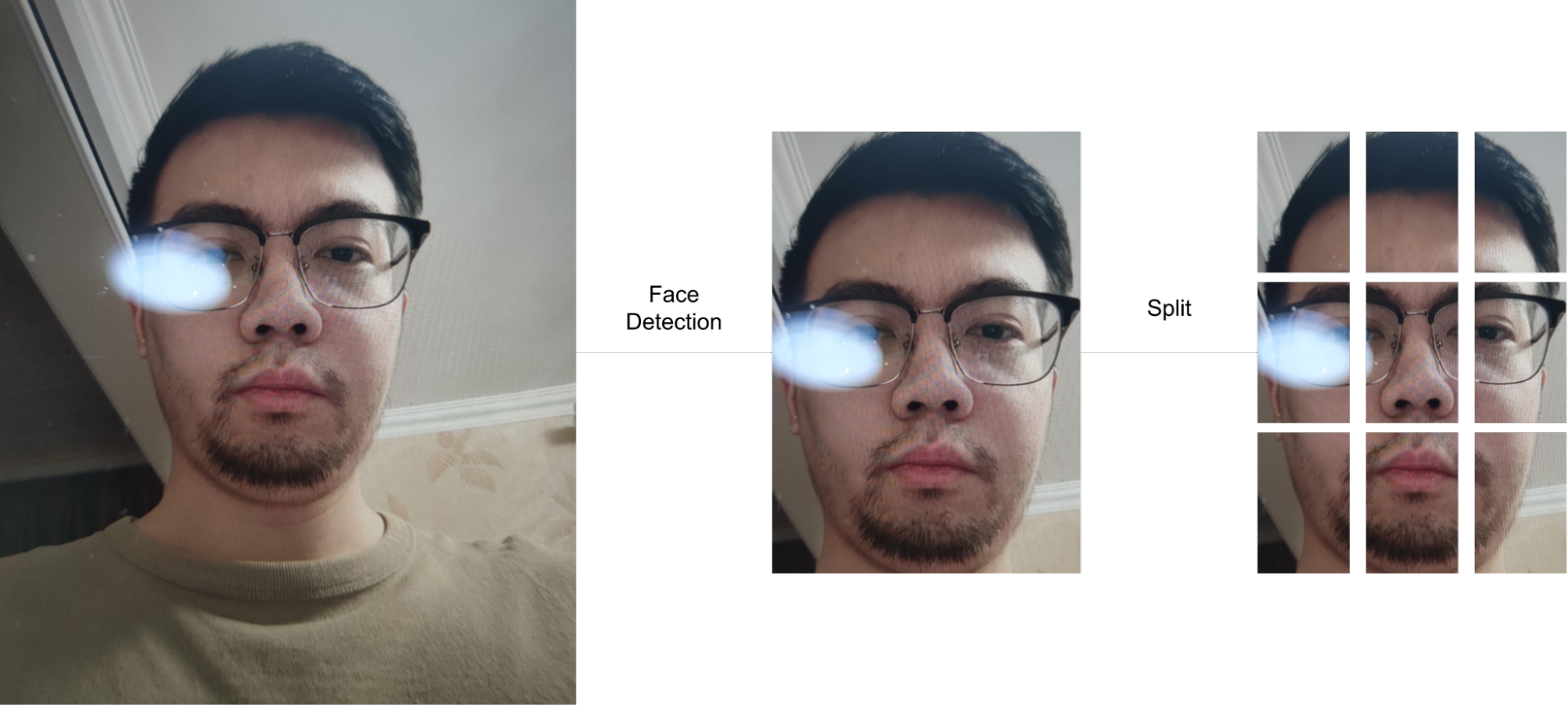

On the other hand, a spoofed face image contains lots of information with subtle spoof cues such as moiré patterns that cannot be detected by the naked eye. As such, it’s important to train the model to identify spoof cues instead of focusing on the possible domain bias between the spoof data and genuine data. To achieve this, we need to change the way we prepare the training data.

Instead of using the entire selfie image as the model input, we firstly detect and crop the face area, then evenly split the cropped face area into several patches. These patches are used as input to train the model. During inference, images are also split into patches the same way and the final result will be the average of outputs from all patches. After this data preprocessing, the patches will contain less global semantic information and more local structure features, making it easier for the model to learn and distinguish spoofed and genuine images.

Face verification

“Data is food for AI.” - Andrew Ng, founder of Google Brain

The key success factors of artificial intelligence (AI) models are undoubtedly driven by the volume and quality of data we hold. At Grab, we have one of the largest and most comprehensive face datasets, covering a wide range of demographic groups in Southeast Asia. This gives us a strong advantage to build a highly robust and unbiased facial recognition model that serves the region better.

As mentioned earlier, all selfies collected by Grab are securely protected under privacy legislation in the countries in which we operate. We take reasonable legal, organisational and technical measures to ensure that your Personal Data is protected, which includes measures to prevent Personal Data from getting lost, or used or accessed in an unauthorised way. We limit access to these Personal Data to our employees on a need to know basis. Those processing any Personal Data will only do so in an authorised manner and are required to treat the information with confidentiality.

Also, selfie data will not be shared with any other parties, including our driver, delivery partners or any other third parties without proper authorisation from the account holder. They are strictly used to improve and enhance our products and services, and not used as a means to collect personal identifiable data. Any disclosure of personal data will be handled in accordance with Grab Privacy Policy.

Other than data, model architecture also plays an important role, especially when handling less common face verification scenarios, such as ”selfie to ID photo” and “selfie to masked selfie” verifications.

The main challenge of “selfie to ID photo” verification is the shallow nature of the dataset, i.e. a large number of unique identities, but a low number of image samples per identity. This type of dataset lacks representation in intra-class diversity, which would commonly lead to model collapse during model training. Besides, “selfie to ID photo” verification also poses numerous challenges that are different from general facial recognition, such as aging (old ID photo), attrited ID card (normal wear and tear), and domain difference between printed ID photo and real-life selfie photo.

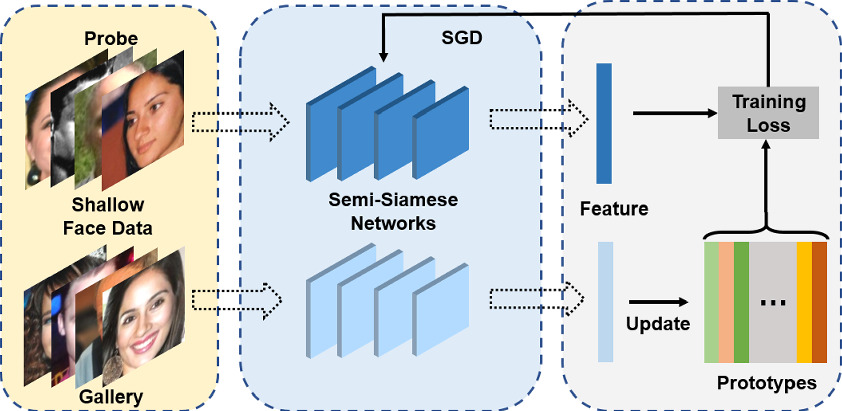

To address these issues, we leveraged a novel training method named semi-Siamese training (SST) 2, which is proposed by Du et al. (2020). The key idea is to enlarge intra-class diversity by ensuring that the backbone Siamese networks have similar parameters, but are not entirely identical, hence the name “semi-Siamese”.

Just like typical Siamese network architecture, feature vectors generated by the subnetworks are compared to compute the loss functions, such as Arc-softmax, Triplet loss, and Large margin cosine loss, all of which aim to reduce intra-class distance while increasing the inter-class distances. With the usage of the semi-Siamese backbone network, intra-class diversity is further promoted as it is guaranteed by the difference between the subnetworks, making the training convergence more stable.

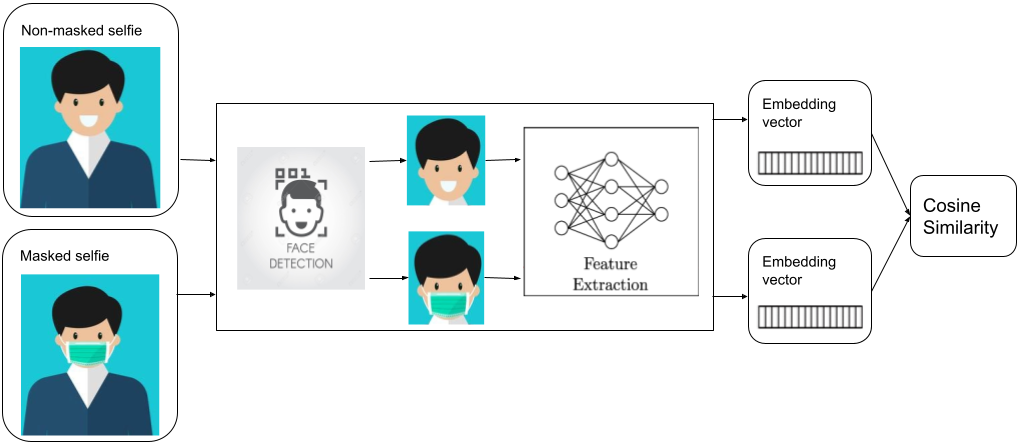

Another type of face verification problem we need to solve these days is the “selfie to masked selfie” verification. To pass this type of face verification, users are required to take off their masks as previous face verification models are unable to verify people with masks on. However, removing face masks to do face verification is inconvenient and risky in a crowded environment, which is a pain for many of our driver-partners who need to do verification from time to time.

To help ease this issue, we developed a face verification model that can verify people even while they are wearing masks. This is done by adding masked selfies into the training data and training the model with both masked and unmasked selfies. This not only enables the model to perform verification for people with masks on, but also helps to increase the accuracy of verifying those without masks. On top of that, masked selfies act as data augmentation and help to train the model with stronger ability of extracting features from the face.

Face search

As previously mentioned, once embeddings are produced by the facial recognition models, face search is fundamentally no different from face verification. Both processes use the distance between embeddings to decide whether the faces belong to the same person. The only difference here is that face search is more computationally expensive, since face verification is a 1-to-1 comparison, whereas face search is a 1-to-N comparison (N=size of the database).

In practice, there are many ways to significantly reduce the complexity of the search algorithm from O(N), such as using Inverted File Index (IVF) and Hierarchical Navigable Small World (HNSW) graphs. Besides, there are also various methods to increase the query speed, such as accelerating the distance computation using GPU, or approximating the distances using compressed vectors. This problem is also commonly known as Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN). Some of the great open-sourced vector similarity search libraries that can help to solve this problem are ScaNN3 (by Google), FAISS4(by Facebook), and Annoy (by Spotify).

What’s next?

In summary, facial recognition technology is an effective crime prevention and reduction tool to strengthen the safety of our platform and users. While the enforcement of selfie collection by itself is already a strong deterrent against fraudsters misusing our platform, leveraging facial recognition technology raises the bar by helping us to quickly and accurately identify these offenders.

As technologies advance, face spoofing patterns also evolve. We need to continuously monitor spoofing trends and actively improve our face anti-spoof algorithms to proactively ensure our users’ safety.

With the rapid growth of facial recognition technology, there is also a growing concern regarding data privacy issues. At Grab, consumer privacy and safety remain our top priorities and we continuously look for ways to improve our existing safeguards.

In May 2022, Grab was recognised by the Infocomm Media Development Authority in Singapore for its stringent data protection policies and processes through the award of Data Protection Trustmark (DPTM) certification. This recognition reinforces our belief that we can continue to draw the benefits from facial recognition technology, while avoiding any misuse of it. As the saying goes, “Technology is not inherently good or evil. It’s all about how people choose to use it”.

Join us

Grab is the leading superapp platform in Southeast Asia, providing everyday services that matter to consumers. More than just a ride-hailing and food delivery app, Grab offers a wide range of on-demand services in the region, including mobility, food, package and grocery delivery services, mobile payments, and financial services across 428 cities in eight countries.

Powered by technology and driven by heart, our mission is to drive Southeast Asia forward by creating economic empowerment for everyone. If this mission speaks to you, join our team today!

References

-

Niu, D., Guo R., and Wang, Y. (2021). Moiré Attack (MA): A New Potential Risk of Screen Photos. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2021/hash/db9eeb7e678863649bce209842e0d164-Abstract.html ↩

-

Du, H., Shi, H., Liu, Y., Wang, J., Lei, Z., Zeng, D., & Mei, T. (2020). Semi-Siamese Training for Shallow Face Learning. European Conference on Computer Vision, 36–53. Springer. ↩

-

Guo, R., Sun, P., Lindgren, E., Geng, Q., Simcha, D., Chern, F., & Kumar, S. (2020). Accelerating Large-Scale Inference with Anisotropic Vector Quantization. International Conference on Machine Learning. https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.10396 ↩

-

Johnson, J., Douze, M., & Jégou, H. (2019). Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs. IEEE Transactions on Big Data, 7(3), 535–547. ↩