Engineering

Engineering

Reliable and Scalable Feature Toggles and A/B Testing SDK at Grab

Imagine this scenario. You’re on one of several teams working on a sophisticated ride allocation service. Your team is responsible for the core booking allocation engine. You’re tasked with increasing the efficiency of the booking allocation algorithm for allocating drivers to passengers. You know this requires a fairly large overhaul of the implementation which will take several weeks. Meanwhile other team members need to continue ongoing work on related areas of the codebase. You need to be able to ship this algorithm in an incomplete state, but dynamically enable it in the testing environment while keeping it disabled in the production environment.

How do you control releasing a new feature like this, or hide a feature still in development? The answer is feature toggling.

Grab’s Product Insights & Experimentation platform provides a dynamic feature toggle capability to our engineering, data, product, and even business teams. Feature toggles also let teams modify system behaviour without changing code.

Grab uses feature toggles to:

-

Gate feature deployment in production to keep new features hidden until product and marketing teams are ready to share.

-

Run experiments (A/B tests) by dynamically changing feature toggles for specific users, rides, etc. For example, a feature can appear only to a particular group of people while running an experiment (treatment group).

Feature toggles, for both experiments and rollouts, let Grab substantially mitigate the risk of releasing immature functionality and try new features safely. If a release has a negative impact, we roll it back. If it’s doing well, we keep rolling it out.

Product and marketing teams then use a web portal to turn features on/off, set up user targeting rules, set various configurations, perform percentage rollouts, and test in production.

Engineers use our solution to run experiments in their server-side application logic. This includes search and recommendation algorithms, pricing & fees, site architecture, outbound marketing campaigns, transactional messaging, and product rollouts.

With experiments, you can perform tests to find out which changes actually work:

-

A/B tests to determine which out of two or more variations, usually minor improvements, produces the best results.

-

Feature tests to safely test a significant change, such as trying out a new feature on a limited audience.

-

Feature rollout to launch a feature (independent of a test). At this stage, you also make the feature available to more users by increasing the traffic allocation to 100%.

Legacy Experimentation

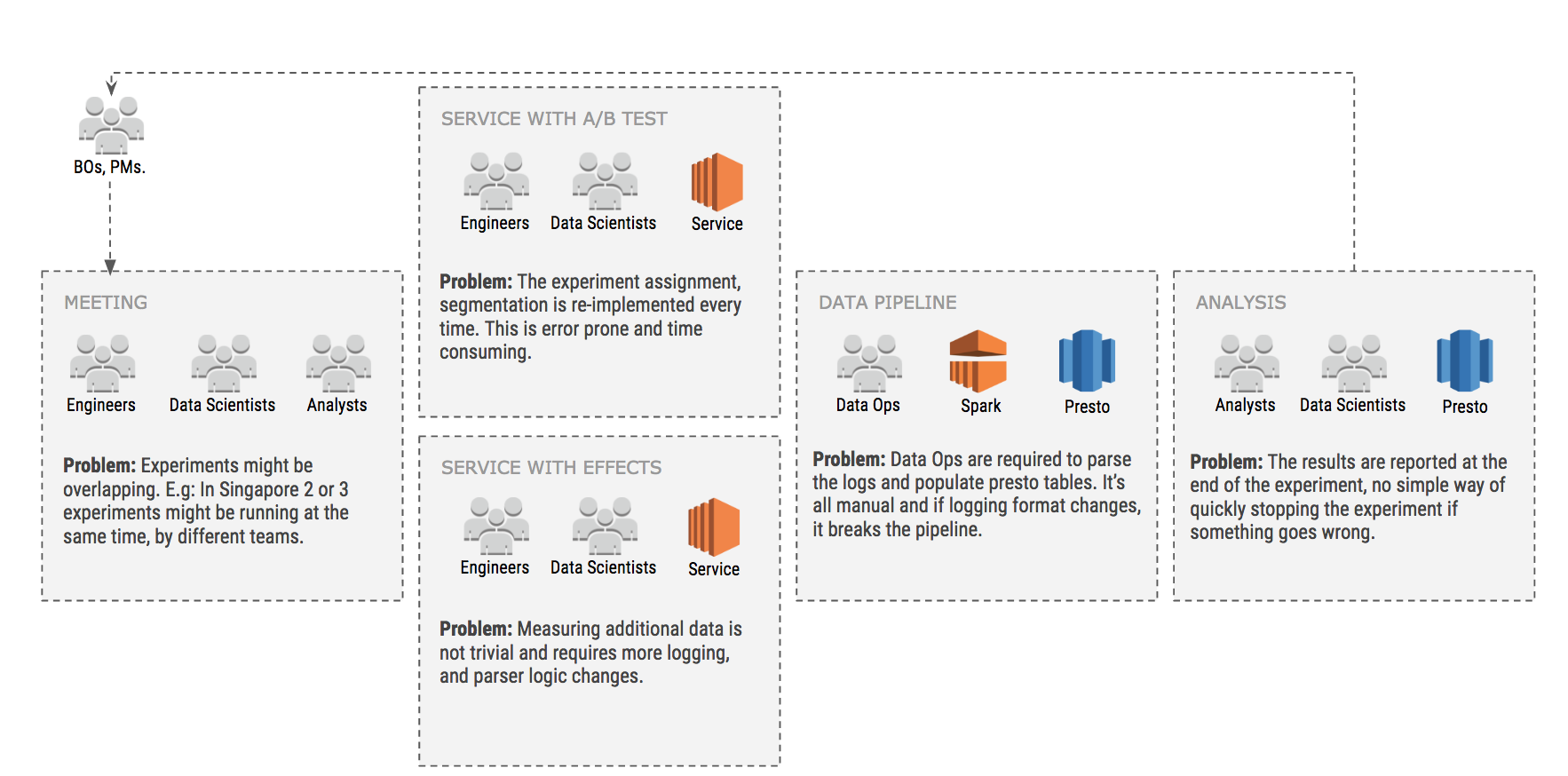

Before 2017, all our experiments were done manually with custom code written here and there in every backend service. As our engineering team grew, this became unsustainable and resulted in excessive friction and endless meetings. The figure below describes problems we used to face before having a centralised experimentation platform. This was an iterative process which sometimes took weeks, slowing down the organisation altogether.

We needed to solve our A/B testing issues and let Grabbers easily integrate and retrieve feature toggle values dynamically. And we needed to that without having network calls and without subjecting our services to unnecessary network jitter, potential latency, and reliability issues.

Moreover, we also needed to track metrics and results of dynamic retrieval. For example, if an A/B test is running on a specific feature toggle, we needed to track what choice was made (i.e. users that got A and those that got B).

Legacy Feature Rollout

Our legacy feature toggling system was essentially a library shipped with all of our Golang services that wrapped calls to a shared Redis. Retrieving values involved network calls and local caching to support our scale, but slowly, as the number of backend microservices grew, it started to become a single point of failure.

// Retrieve a feature flag using our legacy system

sitevar.GetFeatureFlagOrDefault("someFeatureFlagKey", 10, false)

Design Goals of Our SDK

Note: We call a specific feature toggle a variable. In this section, the word “variable” refers to a feature toggle.

To overcome these challenges, we designed an SDK with capabilities to:

-

Retrieve values of variables dynamically

-

Track every retrieval made along with an experiment which might have potentially been applied to the variable. For example, if a user retrieves a value of a variable for a particular passenger, this value along with the context (e.g. passenger, country, time) will be tracked throughout our data logging system.

On the non-functional requirements side, we needed our SDK to be scalable, reliable, and have virtually no latency on the variable retrieval. This meant that we could not make a network call every time we needed a variable. Also, this had to be done asynchronously.

We ended up designing a very simple Go API for our SDK to be used by backend services. The API essentially contains two functions GetVariable() and Track() which are rather self-explanatory - one gets a value of the variable and the other lets users track anything they want.

type Client interface {

// GetVariables with name is either domain or experiment name

GetVariables(ctx context.Context, name string, facets Facets) Variables

// Track an event with a value and metadata*

Track(ctx context.Context, eventName string, value float64, facets Facets)

}

We started the design of the entire platform by designing the APIs first. We wanted to make it simple to use for developers without requiring them to change code each time experiment conditions change or have to move from testing to rollout, and so on. Making the API simple was also crucial as our engineering team grew significantly and the code needed to be very simple to read and understand.

We have also introduced a concept of “facets” which is essentially a set of well-defined attributes used for many different purposes within the platform, from making decisions to tracking and analysing metrics.

Passenger int64 // The passenger identifier

Driver int64 // The driver identifier

Service int64 // The equivalent to a vehicle type

Booking string // The booking code

Location string // The location (geohash or coordinates)

Session string // The session identifier

Request string // The request identifier

Device string // The device identifier

Tag string // The user-defined tag

...

Making Sub-microsecond Decisions

The retrieval of feature toggles is done using the GetVariable() method of the client which takes few parameters:

-

The name of the variable to retrieve. This is essentially the feature toggle name that uniquely identifies a specific product feature or a configuration.

-

The facets representing contextual information about this event and are sent to our data pipeline. In fact, every time GetVariable() is called, an event is automatically generated and reported.

threshold := client.GetVariable(ctx, "myFeature", sdk.NewFacets().

Driver(driverID).

City(cityID)

).Int64(10)

From the code above, note there’s a second step required to actually retrieve the value. In the example we use the method Int64(). It checks if a variable is part of the experiment, converts it to int64, and returns a value.

-

The default value is used when:

-

no experiment and no rollout are configured for that variable or

-

the experiment or rollout are not valid or do not match constraints or

-

some errors occurred.

-

It is important to note that no network I/O happens during the GetVariables() call, as everything is done in the client. The variable tracking is done behind the scenes. The analyst sees it being reflected directly in our data lake, which consists of Simple Storage Service (S3) & Presto.

To make sure no network I/O happens on each GetVariable(), we made our SDK intelligent and formalised both dynamic configurations (we call them rollouts) and experiments. The SDK periodically fetches configurations from S3 and constructs internal, in-memory models to execute.

Let’s start with a rollout definition example. It’s essentially a JSON document with a set of constraints the SDK can evaluate.

{

"variable": "automatedMessageDelay",

"rolloutBy": "city",

"rollouts": [{

"value" : 60,

"string": "60s delay",

"constraints": [

{"target": "city", "op": "=", "value": "6"},

{"target": "svc", "op": "in", "value": "[302, 11]"}

]

},{

"value" : 90,

"string": "90s delay",

"constraints": [

{"target": "city", "op": "=", "value": "10"},

{"target": "pax", "op": "/", "value": "0.25"}

]

}],

"default": 30,

"version": 1515051871,

"schema": 1

}

This definition contains the rollout of the automatedMessageDelay variable.

-

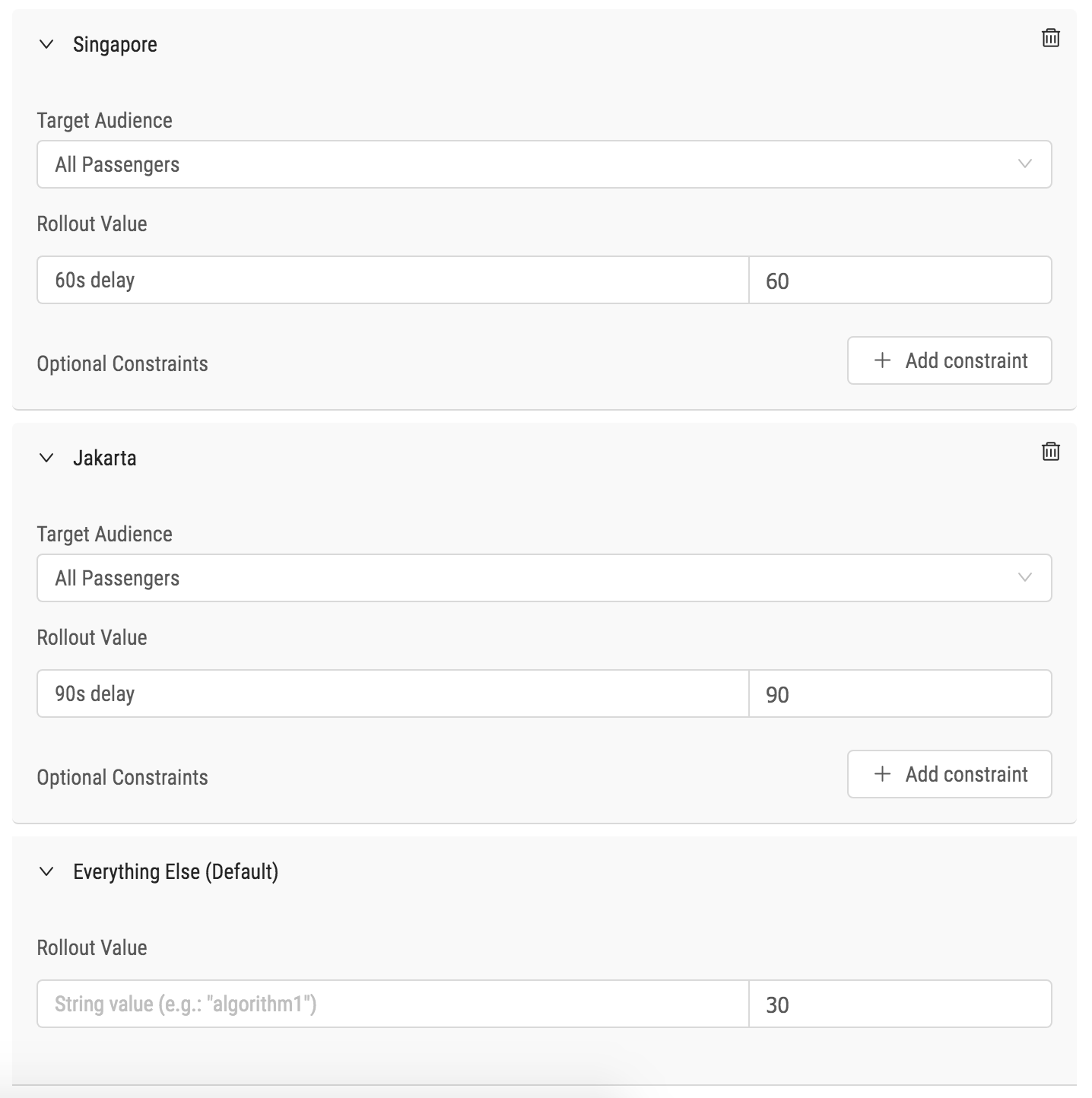

The City facet configures the rollout. This means each city becomes a feature on its own for this variable. We also provide a web-based UI for configuring everything, as shown in the figure below.

-

There are two specific rollouts and one default rollout:

a. For Singapore (City = 6) and Vehicle types 302 and 11, the variable is set to 60.

b. For Jakarta (City = 10) and 25% of Passengers, the variable is set to 90.

c. For everything else, the default rollout value is 30.

-

The rollout definition has a version for auditing and a schema for possible evolution.

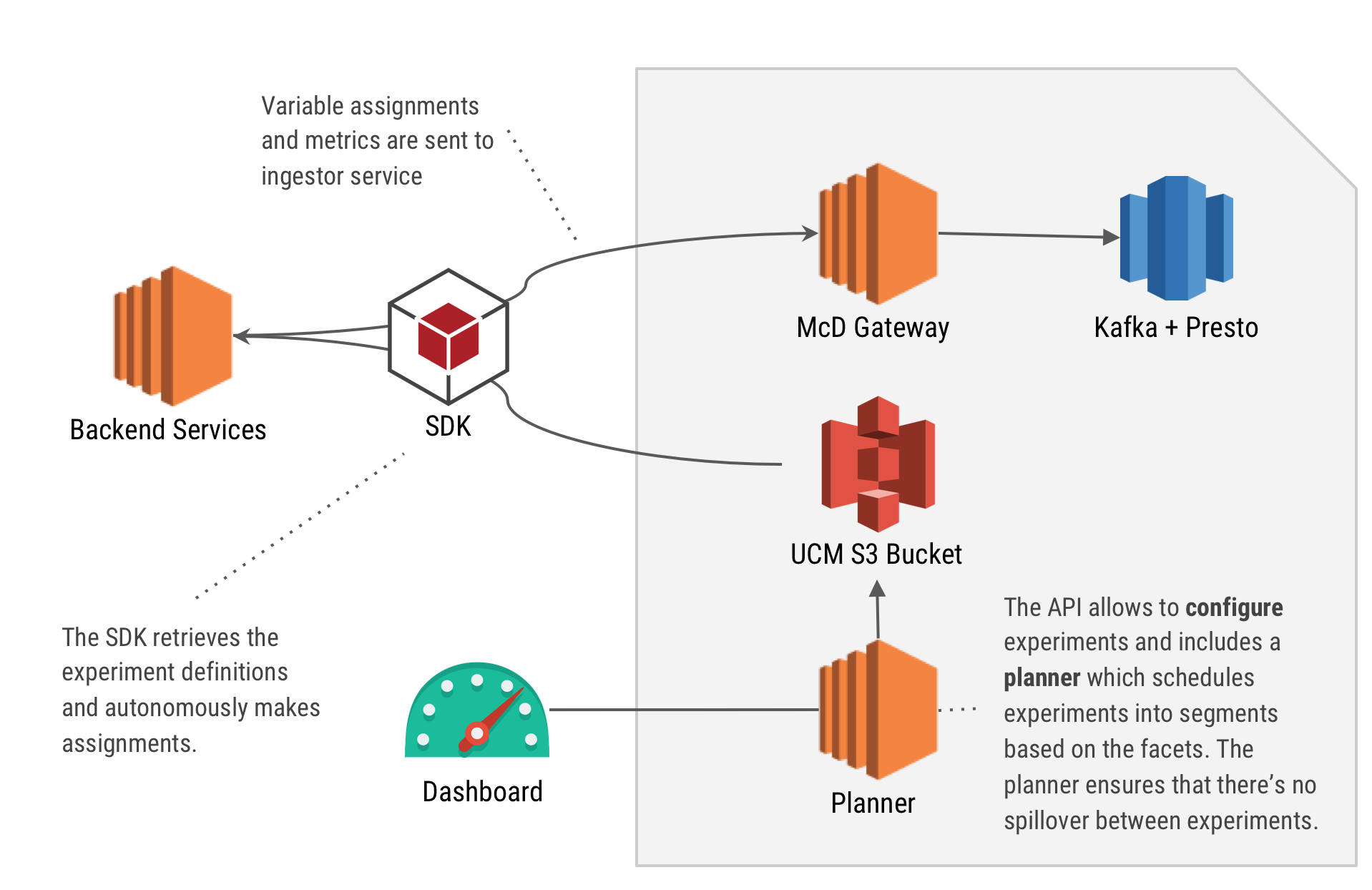

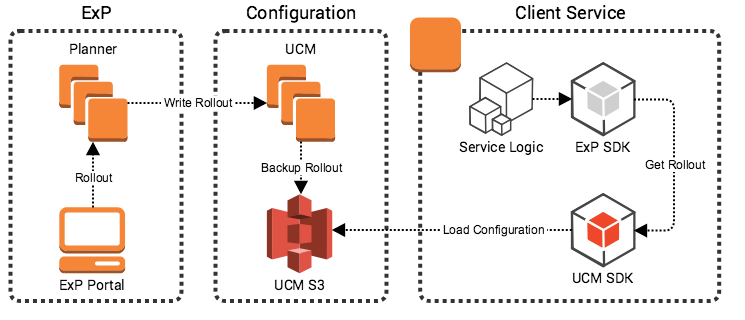

Our SDK uses an internal configuration service to store configurations (the Universal Configuration Manager, or UCM, which uses Amazon S3 behind-the-scenes). All of our backend services poll from UCM and get notified when a configuration is updated. The figure below demonstrates the overall system architecture.

Similarly, we have an experiment configuration with more advanced features such as assignment strategy and values changing dynamically. In the example below, we define an experiment that randomly changes the value between 0 and 1 every 30 seconds..

{

"domain": "primary",

"name": "primary.testTimeSlicedShuffleStrategy",

"variables": [{

"name": "timeSlicedShuffleTest1",

"salt": "primary.testTimeSlicedShuffleStrategy",

"facets": ["ts"],

"strategy": "timeSliceShuffle",

"choices": [{

"value": 0,

"span": 30

}, {

"value": 1,

"span": 30

}]

}],

"constraints": [

{ "target": "ts", "op": ">", "value": "1528714601" },

{ "target": "ts", "op": "<", "value": "1528801001" },

{ "target": "city", "op": "=", "value": "5" }],

"schemaVersion": 1,

"state": "COMPLETED",

"slotting": {

"byPercentage": 0.5

}

}

Similar to the formalisation of feature toggles, we formalised our experiments as JSON files and configured through our configuration store. Everything is done asynchronously and reliably as our services only depend on a Tier-0 AWS Simple Storage Service (S3). Our goal was to keep everything simple and reliable.

Embracing the Binary

As mentioned earlier, our users need the ability to track things. In the SDK, GetVariable() tracks its specified variable value whenever it’s called.

The experimentation platform SDK provides an easy way to track any variable from the code and directly surface it in the presto table for data analysts. Use the client’s Track() method which takes several parameters:

-

The name of the event, which gets prefixed by the service name.

-

The value of the event, which currently can be only a numeric value.

-

The facets representing contextual information about this event. Users are encouraged to provide as much information as possible, for example, passenger ID, booking code, driver ID.

client.Track(ctx, "myEvent", 42, sdk.NewFacets().

Passenger(123).

Booking("ADR-123-2-001").

City(10)

)

We use tracking for reporting when a decision is made. For example, when GetVariable() is called, we need to report whether control or treatment was applied to a particular passenger or booking code. Since there’s no direct network call to get a variable, we internally track every decision and send it to our data pipeline periodically and asynchronously. We also use tracking for capturing important metrics such as the duration of taxi pickup, whether a promotion applied, etc.

When designing tracking, a major goal was to minimise network traffic while keeping performance impact of event reporting small. While this isn’t very important for backend services, we also use the same design for our mobile and web applications. In Southeast Asia, mobile networks may not be great. Also, data can be expensive for our drivers who cannot afford the fastest network plan and the latest iPhone. These business needs must be translated in the design.

So how do we design an efficient protocol for telemetry transmission which keeps both CPU and network use down? We kept it simple, embracing the binary and batch events. We use variable size integer encoding and a minimisation technique for each batch, where once a string is written, it is assigned to an auto-incremented integer value and is written only once to the batch.

This technique did miracles for us and kept network overhead at bay while still keeping our encoding algorithm relatively simple and efficient. It was more efficient than using generic serialisations such as Protocol Buffers, Avro, or JSON.

Results

We have described our feature toggles SDK, but what benefits have we seen? We’ve seen fast adoption of the platform in the company, product managers rolling out features, and data scientists/analysts able to run experiments autonomously. Engineers are happy and things move faster inside the company. This makes us more competitive as an organisation and focused on our consumer’s needs, instead of spending time in meetings and on communication.