Engineering

Engineering

Griffin, an Anti-fraud Risk Rule Engine Making Billions of Predictions Daily

Introduction

At Grab, the scale and fast-moving nature of our business means we need to be vigilant about potential risks to our consumers and to our business. Some of the things we watch for include promotion abuse, or passenger safety on late-night ride allocations. To overcome these issues, the TIS (Trust/Identity/Safety) task force was formed with a group of AI developers dedicated to fraud detection and prevention.

The team’s mission is:

- to keep fraudulent users away from our app or services

- ensure our consumers’ safety, and

- Manage user identities to securely login to the Grab app.

The TIS team’s scope covers not just transport, but also our food, deliver and other Grab verticals.

How We Prevented Fraudulent Transactions in the Earlier Days

In our early days when Grab was smaller, we used a rules-based approach to block potentially fraudulent transactions. Rules are like boolean conditions that determines if the result will be true or false. These rules were very effective in mitigating fraud risk, and we used to create them manually in the code.

We started with very simple rules. For example:

Rule 1:

IF a credit card has been declined today

THEN this card cannot be used for booking

To quickly incorporate rules in our app or service, we integrated them in our backend service code and deployed our service frequently to use the latest rules.

It worked really well in the beginning. Our logic was relatively simple, and only one developer managed the changes regularly. It was very lightweight to trigger the rule deployment and enforce the rules.

However, as the business rapidly expanded, we had to exponentially increase the rule complexity. For example, consider these two new rules:

Rule 2:

IF a credit card has been declined today but this passenger has good booking history

THEN we would still allow this booking to go through, but precharge X amount

Rule 3:

IF a credit card has been declined(but paid off) more than twice in the last 3-months

THEN we would still not allow this booking

The system scans through the rules, one by one, and if it determines that any rule is tripped it will check the other rules. In the example above, if a credit card has been declined more than twice in the last 3-months, the passenger will not be allowed to book even though he has a good booking history.

Though all rules follow a similar pattern, there are subtle differences in the logic and they enable different decisions. Maintaining these complex rules was getting harder and harder.

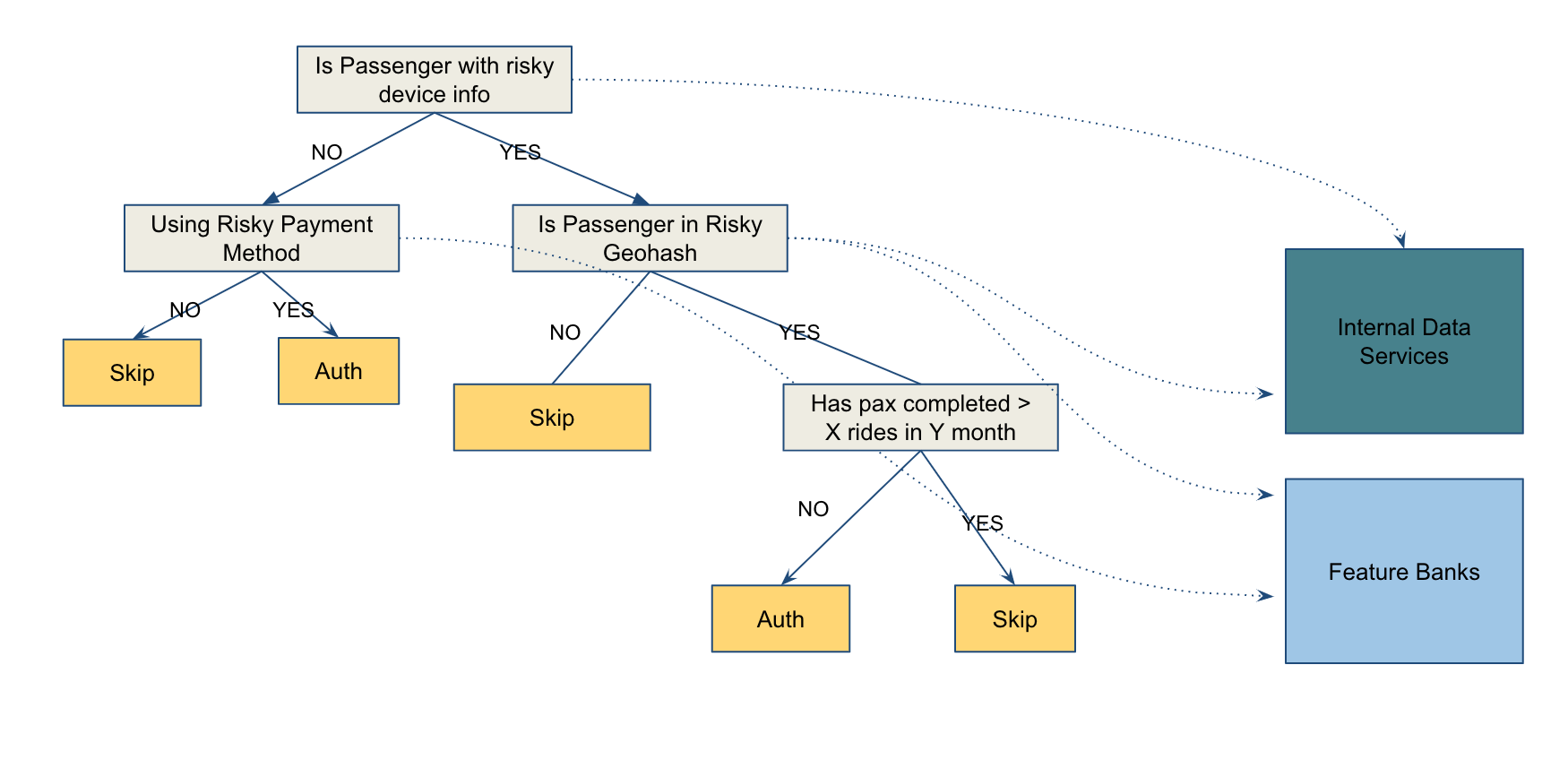

Now imagine we added more rules as shown in the example below. We first check if the device used by the passenger is a high-risk one. e.g using an emulator for booking. If not, we then check the payment method to evaluate the risk (e.g. any declined booking from the credit card), and then make a decision on whether this booking should be precharged or not. If passenger is using a low-risk device but is in some risky location where we traditionally see a lot of fraud bookings, we would then run some further checks about the passenger booking history to decide if a pre-charge is also needed.

Now consider that instead of a single passenger, we have thousands of passengers. Each of these passengers can have a large number of rules for review. While not impossible to do, it can be difficult and time-consuming, and it gets exponentially more difficult the more rules you have to take into consideration. Time has to be spent carefully curating these rules.

The more rules you add to increase accuracy, the more difficult it becomes to take them all into consideration.

Our rules were getting 10X more complicated than the example shown above. Consequently, developers had to spend long hours understanding the logic of our rules, and also be very careful to avoid any interference with new rules.

In the beginning, we implemented rules through a three-step process:

- Data Scientists and Analysts dived deep into our transaction data, and discovered patterns.

- They abstracted these patterns and wrote rules in English (e.g. promotion based booking should be limited to 5 bookings and total finished bookings should be greater than 6, otherwise unallocate current ride)

- Developers implemented these rules and deployed the changes to production

Sometimes, the use of English between steps 2 and 3 caused inaccurate rule implementation (e.g. for “X should be limited to 5”, should the implementation be X < 5 or X <= 5?)

Once a new rule is deployed, we monitored the performance of the rule. For example,

- How often does the rule fire (after minutes, hours, or daily)?

- Is it over-firing?

- Does it conflict with other rules?

Based on implementation, each rule had dependency with other rules. For example, if Rule 1 is fired, we should not continue with Rule 2 and Rule 3.

As a result, we couldn’t keep each rule evaluation independent. We had no way to observe the performance of a rule with other rules interfering. Consider an example where we change Rule 1:

From IF a credit card has been declined today

To IF a credit card has been declined this week

As Rules 2 and 3 depend on Rule 1, their trigger-rate would drop significantly. It means we would have unstable performance metrics for Rule 2 and Rule 3 even though the logic of Rule 2 and Rule 3 does not change. It is very hard for a rule owner to monitor the performance of Rules 2 and Rule 3.

When it comes to the of A/B testing of a new rule, Data Scientists need to put a lot of effort into cleaning up noise from other rules, but most of the time, it is mission-impossible.

After several misfiring events (wrong implementation of rules) and ever longer rule development time (weekly), we realised “No one can handle this manually.“

Birth of Griffin Rule Engine

We decided to take a step back, sit down and closely review our daily patterns. We realised that our daily patterns fall into two categories:

- Fetching new data: e.g. “what is the credit card risk score”, or “how many food bookings has this user ordered in last 7 days”, and transform this data for easier consumption.

- Updating/creating rules: e.g. if a credit card risk score is high, decline a booking.

These two categories are essentially divided into two independent components:

- Data orchestration - collecting/transforming the data from different data sources.

- Rule-based prediction

Based on these findings, we got started with our Data Orchestrator (open sourced at https://github.com/grab/symphony) and Griffin projects.

The intent of Griffin is to provide data scientists and analysts with a way to add new rules to monitor, prevent, and detect fraud across Grab.

Griffin allows technical novices to apply their fraud expertise to add very complex rules that can automate the review of rules without manual intervention.

Griffin now predicts billions of events every day with 100K+ Queries per second(QPS) at peak time (on only 6 regular EC2s).

Data scientists and analysts can self-service rule changes on the web portal directly, deploy rules with just a few clicks, experiment and monitor performance in real time.

Why We Came up with Griffin Instead of Using Third-party Tools in the Market

Before we decided to create our in-built tool, we did some research for common business rule engines available in the market such as Drools and checked if we should use them. In that process, we found:

- Drools has its own Java-based DSL with a non-trivial learning curve (whereas our major users are from Python background).

- Limited [expressive power](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expressive_power_(computer_science),

- Limited support for some common math functions (e.g. factorial/ Greatest Common Divisor).

- Our nature of business needed dynamic dataset for predictions (for example, a rule may need only passenger booking history on Day 1, but it may use passenger booking history, passenger credit balance, and passenger favourite places on Day 2). On the other hand, Drools usually works well with a static list of dataset instead of dynamic dataset.

Given the above constraints, we decided to build our own rule engine which can better fit our needs.

Griffin Architecture

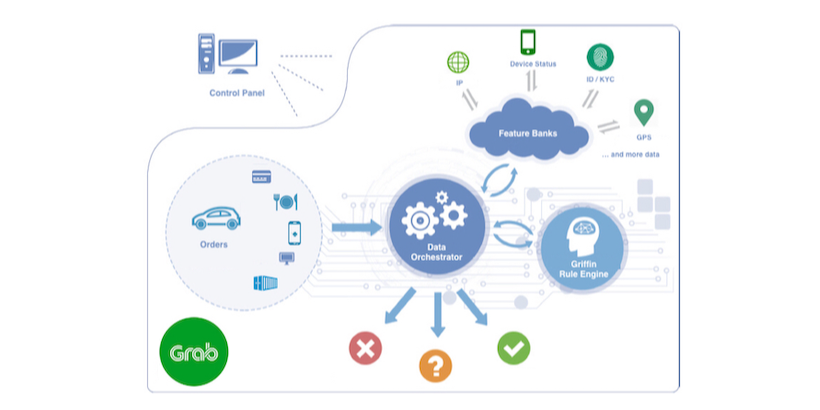

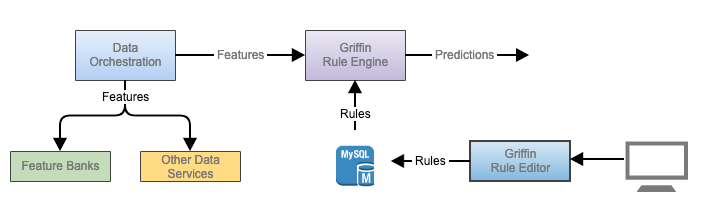

The diagram depicts the high-level flow of making a prediction through Griffin.

Components

- Data Orchestration: a service that collects all data needed for predictions

- Rule Engine: a service that makes prediction based on rules

- Rule Editor: the portal through which users can create/update rules

Workflow

- Users create/update rules in the Rule Editor web portal, and save the rules in the database.

- Griffin Rule Engine reloads rules immediately as long as it detects any rule changes.

- Data Orchestrator sends all dataset (features) needed for a prediction (e.g. whether to block a ride based on passenger past ride pattern, credit card risk) to the Rule Engine

- Griffin Rule Engine makes a prediction.

How You can Create Rules Using Griffin

In an abstract view, a rule inside Griffin is defined as:

Rule:

Input:JSON => Result:Boolean

We allow users (analysts, data scientists) to write Python-based rules on WebUI to accommodate some very complicated rules like:

len(list(filter(lambdax: x \>7, (map(lambdax: math.factorial(x), \[1,2,3,4,5,6\]))))) \>2

This significantly optimises the expressive power of rules.

To match and evaluate a rule more efficiently, we also have other key components associated:

Scenarios

- Here are some examples:

PreBooking,PostBookingCompletion,PostFoodDelivery

Actions

- Actions such as

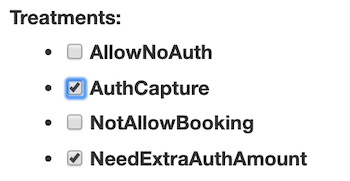

NotAllowBooking,AuthCapture,SendNotification - If a rule result is True, it returns a list of treatments as selected by users, e.g. AuthCapture and SendNotification (the example below is treatments for one Safety-related rule).The one below is for a checkpoint to detect credit-card risk.

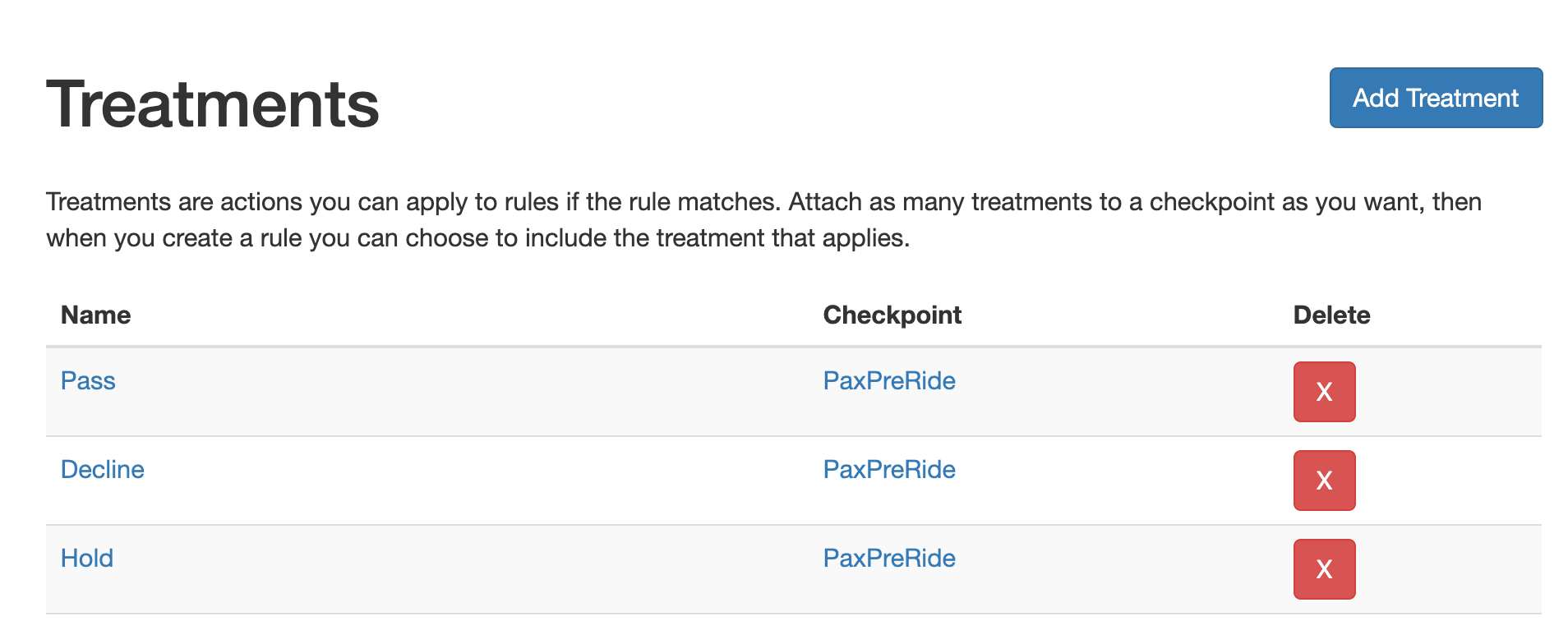

- Each checkpoint has a default treatment. If no rule inside this checkpoint is hit, the rule engine would return the default one (in most cases, it is just “do nothing”).

- A treatment can only belong to one checkpoint, but one checkpoint can have multiple treatments.

For example, the graph below demonstrates a checkpoint PaxPreRide associated with three treatments: Pass, Decline, Hold

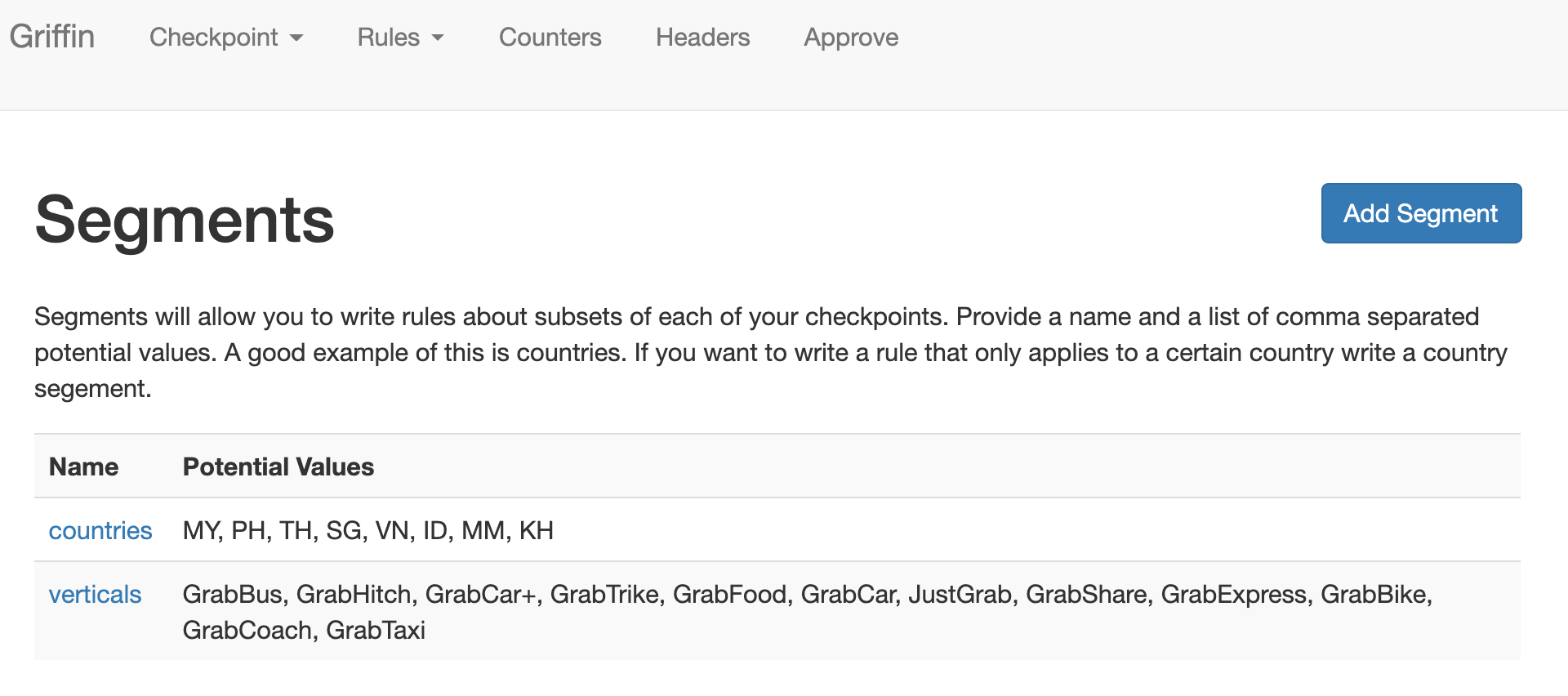

Segments

- The scope/dimension of a rule. Based on the sample segments below, a rule can be applied only to

countries=\[MY,PH\]andverticals=\[GrabBus, GrabCar\] - It can be changed at any time on WebUI as well.

Values of a rule When a rule is hit, more than just treatments, users also want some dynamic values returned. E.g. a max distance of the ride allowed if we believe this booking is medium risk.

Does Python Make Griffin Run Slow?

We picked Python to enjoy its great expressive power and neatness of syntax, but some people ask: Python is slow, would this cause a latency bottleneck?

Our answer is No.

The following graph shows the Latency P99 of Prediction Request from load balancer side (actually the real latency for each prediction is < 6ms, the metrics are peaked at 30ms because some batch requests contain 50 predictions in a single call).

What We Did to Achieve This

- The key idea is to make all computations in CPU and memory only (in other words, no extra I/O).

- We do not fetch the rules from database for each prediction. Instead, we keep a record called

dirty_key, which keeps the latest rule update timestamp. The rule engine would actively check this timestamp and trigger a rule reload only when thedirty_keytimestamp in the DB is newer than the latest rule reload time. - Rule engine would not fetch any additional new data, instead, all data should be from Data Orchestrator.

- So the whole prediction flow is only between CPU & memory (and if the data size is small, it could be on CPU cache only).

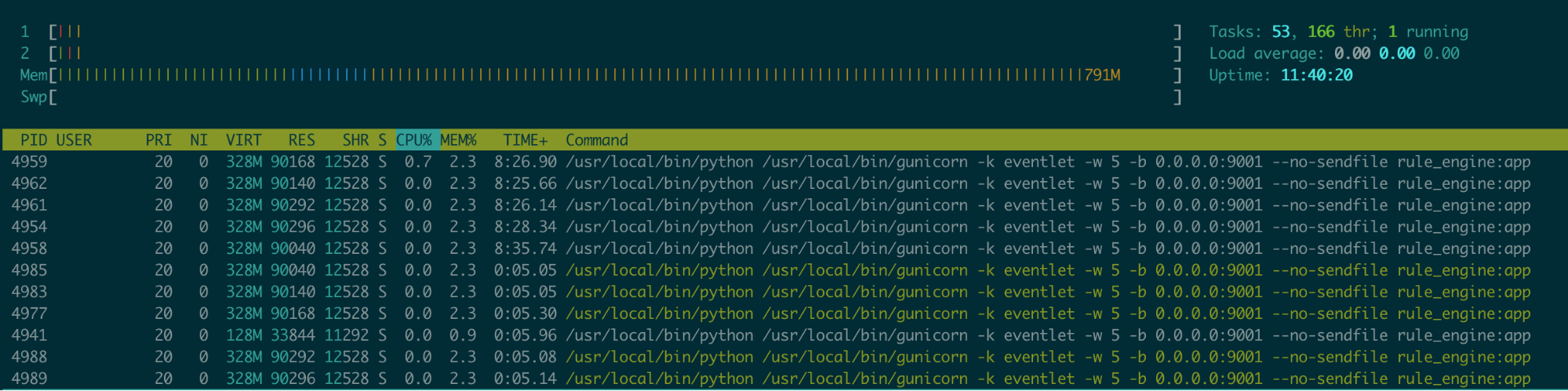

- Python GIL essentially enforces a process to have up to one active thread running at a time, no matter how many cores a CPU has. We have Gunicorn to wrap our service, so on the Production machine, we have

(2x$num_cores) + 1 processes(see Gunicorn Design - How Many Workers?). The formula is based on the assumption that for a given core, one worker will be reading or writing from the socket while the other worker is processing a request.

The following screenshot is the process snapshot on C5.large machine with 2 vCPU. Note only green processes are active.

A lot of trial and error performance tuning:

- We used to have python-jsonpath-rw for JSONPath query, but the performance was not strong enough. We switched to jmespath and observed about 10ms latency reduction.

- We use sqlalchemy for DB Query and ORM. We enabled cache for some use cases, but turned out it was over-optimised with stale data. We ended up turning off some caching points to ensure the data consistency.

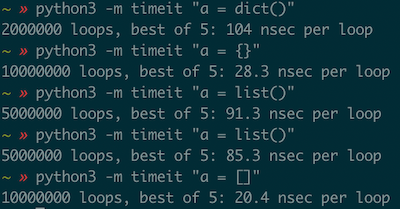

- For new dict/list creation, we prefer native call (e.g.

{}/[]) instead of function call (see the comparison below).

- Use built-in functions https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html. It is written in C, no one can beat it.

- Add randomness to rule reload so that not all machines run at the same time causing latency spikes.

- Caching atomic feature units as they are used so that we don’t have to requery for them each time a checkpoint uses it.

How Griffin Makes On-call Engineers Relax

One of the most popular aspects of Griffin is the WebUI. It opens a door for non-developers to make production changes in real time which significantly boosts organisation productivity. In the past a rule change needed 1 week for code change/test/deployment, now it is just 1 minute.

But this also introduces extra risks. Anyone can turn the whole checkpoint down, whether unintentionally or maliciously.

Hence we implemented Shadow Mode and Percentage-based rollout for each rule. Users can put a rule into Shadow Mode to verify the performance without any production impact, and if needed, rollout of a rule can be from 1% all the way to 100%.

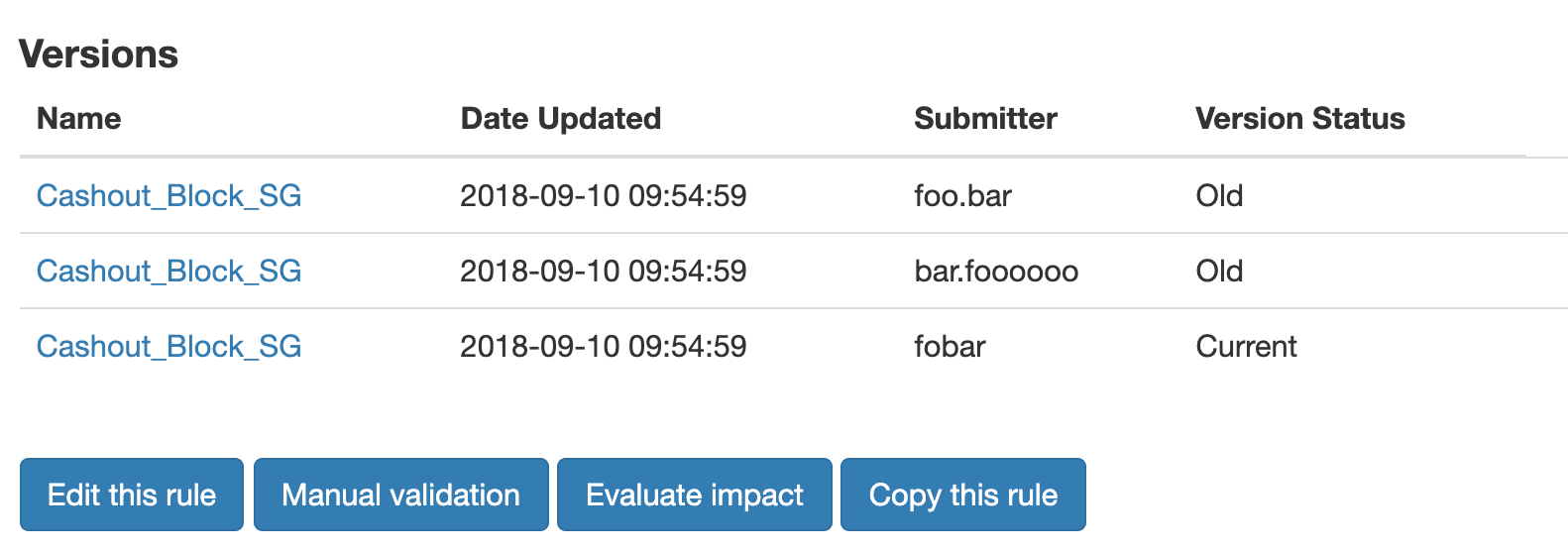

We implemented version control for every rule change, and in case anything unexpected happened, we could rollback to the previous version quickly.

We also built RBAC-based permission system, along with Change Approval flow to make sure any prod change needs at least two people(and approver role has higher permission)

Closing Thoughts

Griffin evolved from a fraud-based rule engine to generic rule engine. It can apply to any rule at Grab. For example, Grab just launched Appeal automation several days ago to reduce 50% of the human effort it typically takes to review straightforward appeals from our passengers and drivers. It was an unplanned use case, but we are so excited about this.

This could happen because from the very beginning we designed Griffin with minimised business context, so that it can be generic enough.

After the launch of this, we observed an amazing adoption rate for various fraud/safety/identity use cases. More interestingly, people now treat Griffin as an automation point for various integration points.

Speak to us

GrabDefence is a proprietary fraud prevention platform built by Grab, Southeast Asia’s leading superapp. Since 2019, the GrabDefence team has shared its fraud management capabilities and platform with enterprises and startups to leverage Grab’s advanced AI/ML models, hyper local insights and patented device intelligence technologies.

To learn more about GrabDefence or to speak to our fraud management experts, contact us at gd.contact@grabtaxi.com.