Engineering

Engineering

Our Journey to Continuous Delivery at Grab (Part 1)

This blog post is a two-part presentation of the effort that went into improving the continuous delivery processes for backend services at Grab in the past two years. In the first part, we take stock of where we started two years ago and describe the software and tools we created while introducing some of the integrations we’ve done to automate our software delivery in our staging environment.

— continuousdelivery.com

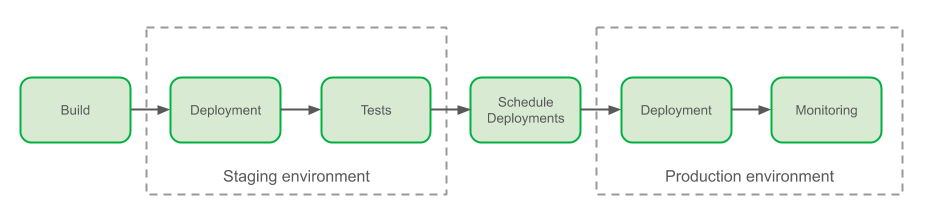

As a backend engineer at Grab, nothing matters more than the ability to innovate quickly and safely. Around the end of 2018, Grab’s transportation and deliveries backend architecture consisted of roughly 270 services (the majority being microservices). The deployment process was lengthy, required careful inputs and clear communication. The care needed to push changes in production and the risk associated with manual operations led to the introduction of a Slack bot to coordinate deployments. The bot ensures that deployments occur only during off-peak and within work hours:

Once the build was completed, engineers who desired to deploy their software to the Staging environment would copy release versions from the build logs, and paste them in a Jenkins job’s parameter. Tests needed to be manually triggered from another dedicated Jenkins job.

Prior to production deployments, engineers would generate their release notes via a script and update them manually in a wiki document. Deployments would be scheduled through interactions with a Slack bot that controls release notes and deployment windows. Production deployments were made once again by pasting the correct parameters into two dedicated Jenkins jobs, one for the canary (a.k.a. one-box) deployment and the other for the full deployment, spread one hour apart. During the monitoring phase, engineers would continuously observe metrics reported on our dashboards.

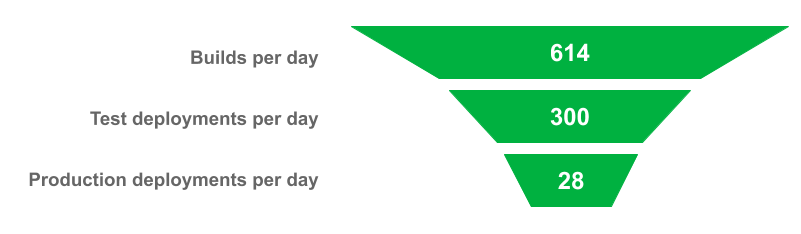

In spite of the fragmented process and risky manual operations impacting our velocity and stability, around 614 builds were running each business day and changes were deployed on our staging environment at an average rate of 300 new code releases per business day, while production changes averaged a rate of 28 new code releases per business day.

These figures meant that, on average, it took 10 business days between each service update in production, and only 10% of the staging deployments were eventually promoted to production.

Automating Continuous Deployments at Grab

With an increased focus on Engineering efficiency, in 2018 we started an internal initiative to address frictions in deployments that became known as Conveyor. To build Conveyor with a small team of engineers, we had to rely on an already mature platform which exhibited properties that are desirable to us to achieve our mission.

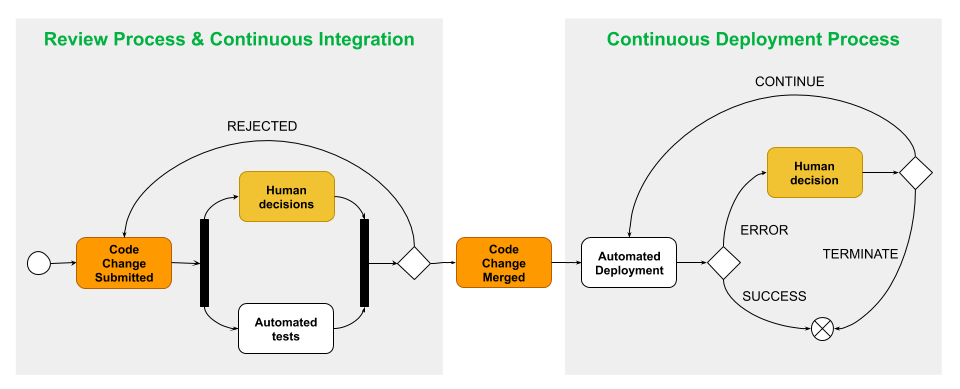

Hands-off Deployments

Deployments should be an afterthought. Engineers should be as removed from the process as possible, and whenever possible, decisions should be taken early, during the code review process. The machine will do the heavy lifting, and only when it can’t decide for itself, should the engineer be involved. Notifications can be leveraged to ensure that engineers are only informed when something goes wrong and a human decision is required.

Confidence in Deployments

Grab’s focus on gathering internal Engineering NPS feedback helped us collect valuable metrics. One of the metrics we cared about was our engineers’ confidence in their production deployments. A team’s entire deployment process to production could last for more than a day and may extend up to a week for teams with large infrastructures running critical services. The possibility of losing progress in deployments when individual steps may last for hours is detrimental to the improvement of Engineering efficiency in the organisation. The deployment automation platform is the bedrock of that confidence. If the platform itself fails regularly or does provide a path of upgrade that is transparent to end-users, any features built on top of it would suffer from these downtimes and ultimately erode confidence in deployments.

Tailored to Most But Extensible for the Few

Our backend engineering teams are working on diverse stacks, and so are their deployment processes. Right from the start, we wanted our product to benefit the largest population of engineers that had adopted the same process, so as to maximise returns on our investments. To ease adoption, we decided to tailor a deployment pipeline such that:

- It would model the exact sequence of manual processes followed by this population of engineers.

- Switching to use that pipeline should require as little work as possible by service teams.

However, in cases where this model would not fit a team’s specific process, our deployment platform should be open and extensible and support new customisations even when they are not originally supported by the product’s ecosystem.

Cloud-agnosticity

While we were going to target a specific process and team, to ensure that our solution would stand the test of time, we needed to ensure that our solution would support the variety of environments currently used in production. This variety was also likely to increase, and we wanted a platform that would mature together with the rest of our ecosystem.

Overview Of Conveyor

Setting Sail with Spinnaker

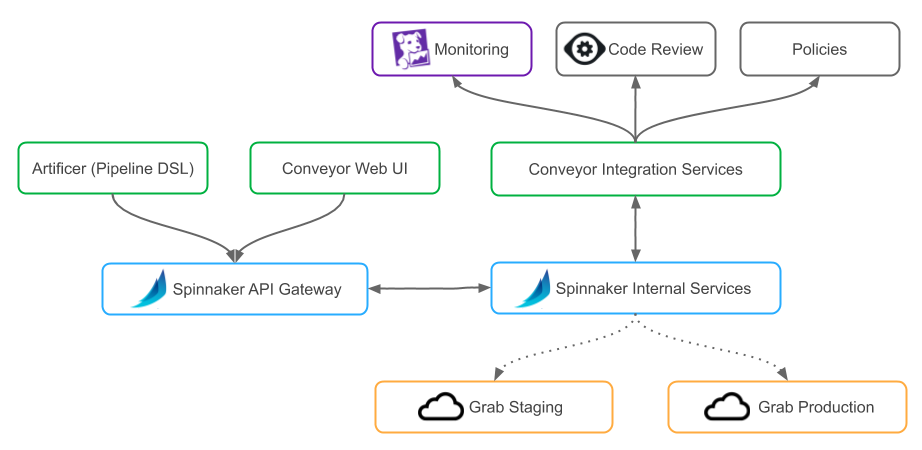

Conveyor is based on Spinnaker, an open-source, multi-cloud continuous delivery platform. We’ve chosen Spinnaker over other platforms because it is a mature deployment platform with no single point of failure, supports complex workflows (referred to as pipelines in Spinnaker), and already supports a large array of cloud providers. Since Spinnaker is open-source and extensible, it allowed us to add the features we needed for the specificity of our ecosystem.

To further ease adoption within our organization, we built a tailored user interface and created our own domain-specific language (DSL) to manage its pipelines as code.

Onboarding to a Simpler Interface

Spinnaker comes with its own interface, it has all the features an engineer would want from an advanced continuous delivery system. However, Spinnaker interface is vastly different from Jenkins and makes for a steep learning curve.

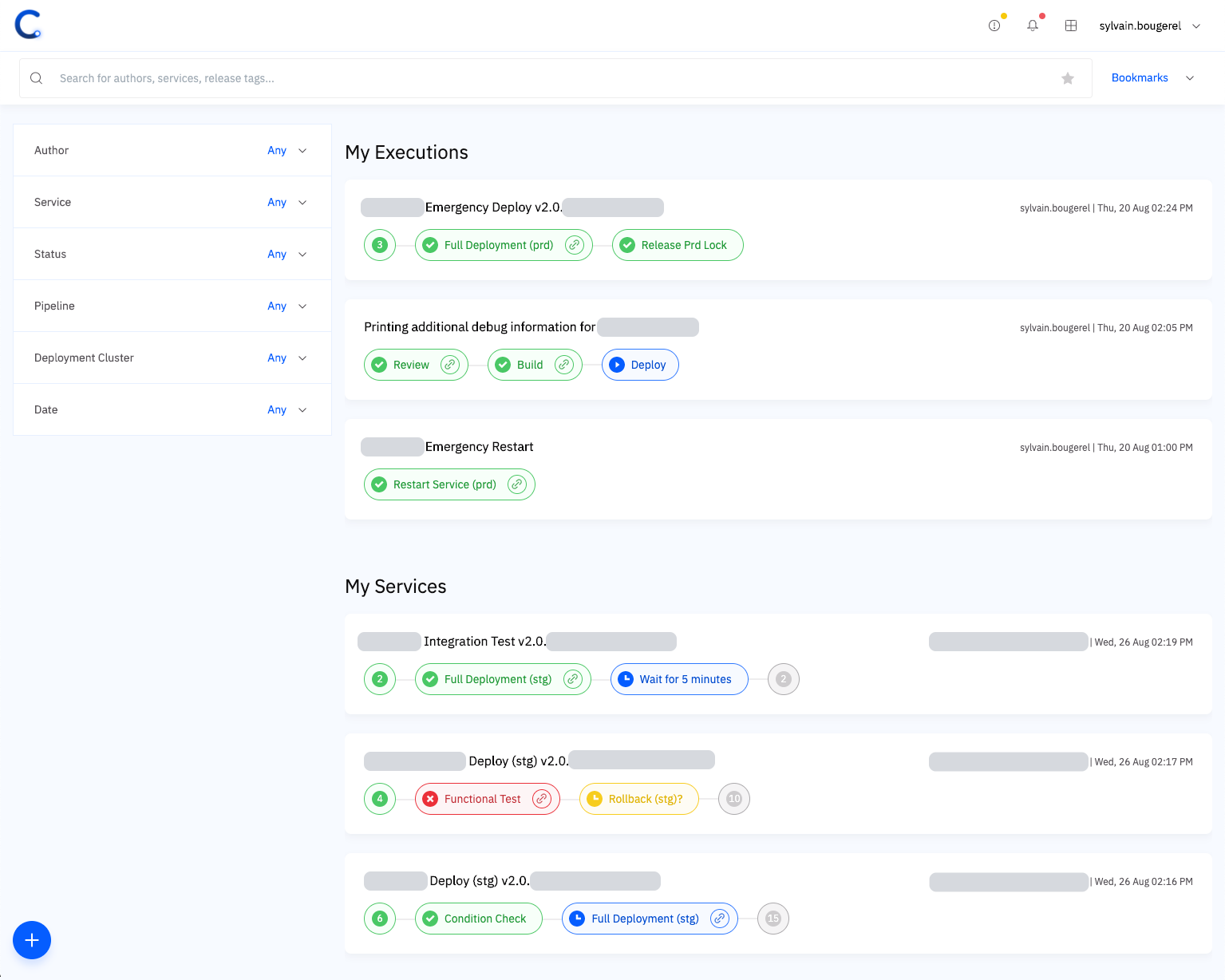

To reduce our barrier to adoption, we decided early on to create a simple interface for our users. In this interface, deployment pipelines take the center stage of our application. Pipelines are objects managed by Spinnaker, they model the different steps in the workflow of each deployment. Each pipeline is made up of stages that can be assembled like lego-bricks to form the final pipeline. An instance of a pipeline is called an execution.

With this interface, each engineer can focus on what matters to them immediately: the pipelines they have started, or those started by other teammates working on the same services as they are. Conveyor also provides a search bar (on the top) and filters (on the left) that work in concert to explore all pipelines executed at Grab.

We adopted a consistent set of colours to model all information in our interface:

- blue: represent stages that are currently running;

- red: stages that have failed or important information;

- yellow: stages that require human interaction;

- and finally, in green: stages that were successfully completed.

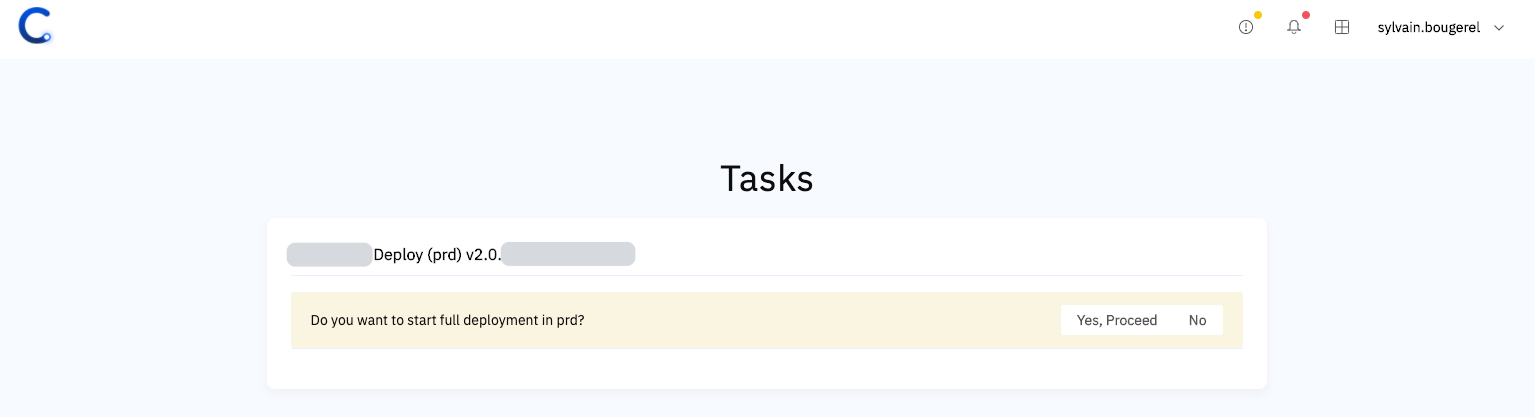

Conveyor also provides a task and notifications area, where all stages requiring human intervention are listed in one location. Manual interactions are often no more than just YES or NO questions:

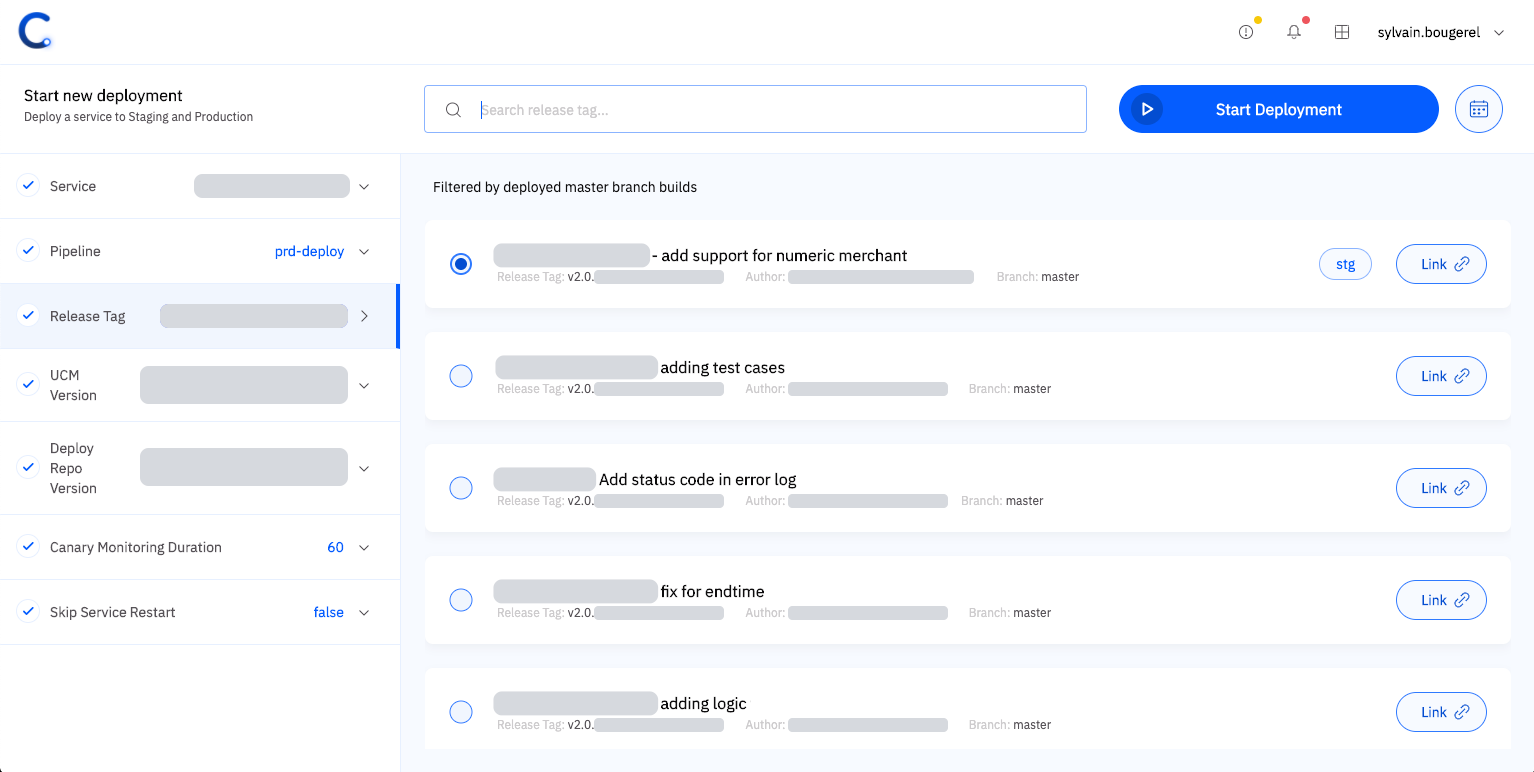

Finally, in addition to supporting automated deployments, we greatly simplified the start of manual deployments. Instead of being required to copy/paste information, each parameter can be selected on the interface from a set of predefined items, sorted chronologically, and presented with contextual information to help engineers in their decision.

Several parameters are required for our deployments and their values are selected from the UI to ensure correctness.

Ease of Adoption with Our Pipeline-as-code DSL

Ease of adoption for the team is not simply about the learning curve of the new tools. We needed to make it easy for teams to configure their services to deploy with Conveyor. Since we focused on automating tasks that were already performed manually, we needed only to configure the layer that would enable the integration.

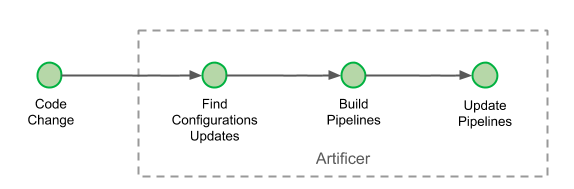

We set on creating a pipeline-as-code implementation when none were widely being developed in the Spinnaker community. It’s interesting to see that two years on, this idea has grown in parallel in the community, with the birth of other pipeline-as-code implementations. Our pipeline-as-code is referred to as the Pipeline DSL, and its configuration is located inside each team’s repository. Artificer is the name of our Pipeline DSL interpreter and it runs with every change inside our monorepository:

Pipelines are being updated at every commit if necessary.

Creating a conveyor.jsonnet file within the service’s directory of our monorepository with the few lines below is all that’s required for Artificer to do its work and get the benefits of automation provided by Conveyor’s pipeline:

local default = import 'default.libsonnet';

[

{

name: "service-name",

group: [

"group-name",

]

}

]

Sample minimal conveyor.jsonnet configuration to onboard services.

In this file, engineers simply specify the name of their service and the group that a user should belong to, to have deployment rights for the service.

Once the build is completed, teams can log in to Conveyor and start manual deployments of their services with our pipelines. Three pipelines are provided by default: the integration pipeline used for tests and developments, the staging pipeline used for pre-production tests, and the production pipeline for production deployment.

Thanks to the simplicity of this minimal configuration file, we were able to generate these configuration files for all existing services of our monorepository. This resulted in the automatic onboarding of a large number of teams and was a major contributing factor to the adoption of Conveyor throughout our organisation.

Our Journey to Engineering Efficiency (for Backend Services)

The sections below relate some of the improvements in engineering efficiency we’ve delivered since Conveyor’s inception. They were not made precisely in this order but for readability, they have been mapped to each step of the software development lifecycle.

Automate Deployments at Build Time

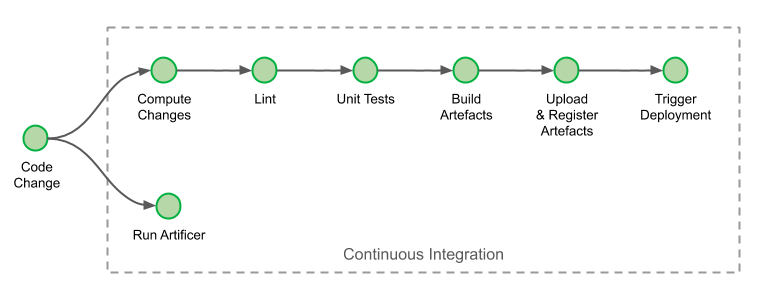

Continuous delivery begins with a pushed code commit in our trunk-based development flow. Whenever a developer pushes changes onto their development branch or onto the trunk, a continuous integration job is triggered on Jenkins. The products of this job (binaries, docker images, etc) are all uploaded into our artefact repositories. We’ve made two additions to our continuous integration process.

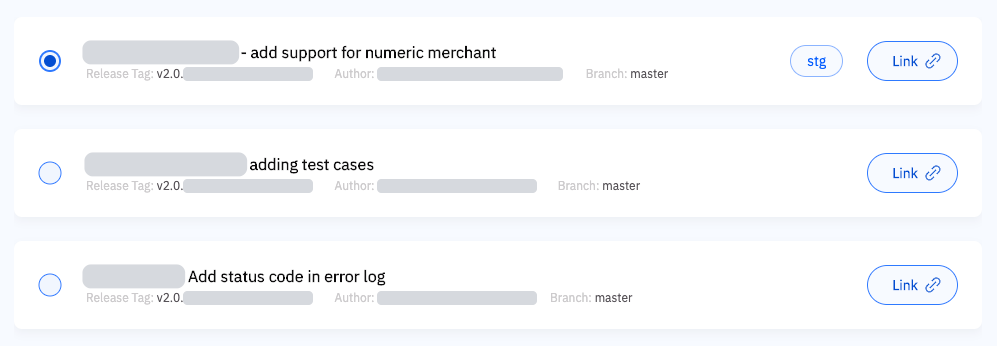

The first modification happens at the step “Upload & Register artefacts”. At this step, each artefact created is now registered in Conveyor with its associated metadata. When and if an engineer needs to trigger a deployment manually, Conveyor can display the list of versions to choose from, eliminating the need for error-prone manual inputs:

Each selectable version shows contextual information: title, author, version and link to the code change where it originated. During registration, the commit time is also recorded and used to order entries chronologically in the interface. To ensure this integration is not a single point of failure for deployments, manual input is still available optionally.

The second modification implements one of the essential feature continuous delivery: your deployments should happen often, automatically. Engineers are now given the possibility to start automatic deployments once continuous integration has successfully completed, by simply modifying their project’s continuous integration settings:

{

"AfterBuild": [

{

"AutoDeploy": {

"OnDiff": false,

"OnLand": true

},

"TYPE": "conveyor"

}

],

// other settings...

}

Sample settings needed to trigger auto-deployments. Diff refers to code review submissions, and Land refers to merged code changes.

Staging Pipeline

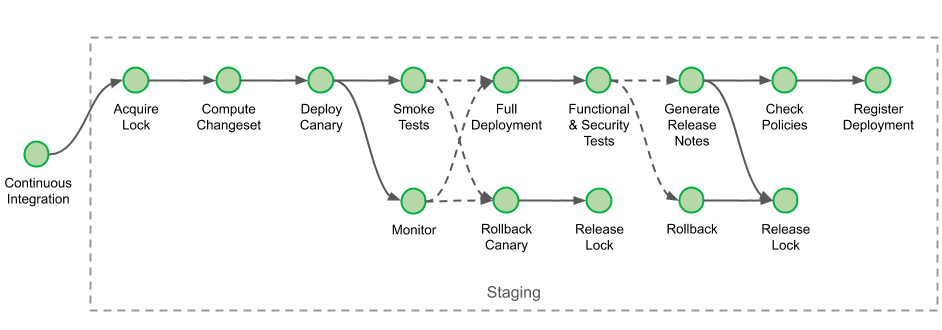

Before deploying a new artefact to a service in production, changes are validated on the staging environment. During the staging deployment, we verify that canary (one-box) deployments and full deployments with automated smoke and functional tests suites.

We start by acquiring a deployment lock for this service and this environment. This prevents another deployment of the same service on the same environment to happen concurrently, other deployments will be waiting in a FIFO queue until the lock is released.

The stage “Compute Changeset” ensures that the deployment is not a rollback. It verifies that the new version deployed does not correspond to a rollback by comparing the ancestry of the commits provided during the artefact registration at build time: since we automate deployments after the build process has completed, cases of rollback may occur when two changes are created in quick succession and the latest build completes earlier than the older one.

After the stage “Deploy Canary” has completed, smoke test run. There are three kinds of tests executed at different stages of the pipeline: smoke, functional and security tests. Smoke tests directly reach the canary instance’s endpoint, by-passing load-balancers. If the smoke tests fail, the canary is immediately rolled back and this deployment is terminated.

All tests are generated from the same builds as the artefact being tested and their versions must match during testing. To ensure that the right version of the test run and distinguish between the different kind of tests to perform, we provide additional metadata that will be passed by Conveyor to the tests system, known internally as Gandalf:

local default = import 'default.libsonnet';

[

{

name: "service-name",

group: [

"group-name",

],

gandalf_smoke_tests: [

{

path: "repo.internal/path/to/my/smoke/tests"

}

],

gandalf_functional_tests: [

{

path: "repo.internal/path/to/my/functional/tests"

}

],

gandalf_security_tests: [

{

path: "repo.internal/path/to/my/security/tests"

}

]

}

]

Sample conveyor.jsonnet configuration with integration tests added.

Additionally, in parallel to the execution of the smoke tests, the canary is also being monitored from the moment its deployment has completed and for a predetermined duration. We leverage our integration with Datadog to allow engineers to select the alerts to monitor. If an alert is triggered during the monitoring period, and while the tests are executed, the canary is again rolled back, and the pipeline is terminated. Engineers can specify the alerts by adding them to the conveyor.jsonnet configuration file together with the monitoring duration:

local default = import 'default.libsonnet';

[

{

name: "service-name",

group: [

"group-name",

],

gandalf_smoke_tests: [

{

path: "repo.internal/path/to/my/smoke/tests"

}

],

gandalf_functional_tests: [

{

path: "repo.internal/path/to/my/functional/tests"

}

],

gandalf_security_tests: [

{

path: "repo.internal/path/to/my/security/tests"

}

],

monitor: {

stg: {

duration_seconds: 300,

alarms: [

{

type: "datadog",

alert_id: 12345678

},

{

type: "datadog",

alert_id: 23456789

}

]

}

}

}

]

Sample conveyor.jsonnet configuration with alerts in staging added.

When the smoke tests and monitor pass and the deployment of new artefacts is completed, the pipeline execution triggers functional and security tests. Unlike smoke tests, functional & security tests run only after that step, as they communicate with the cluster through load-balancers, impersonating other services.

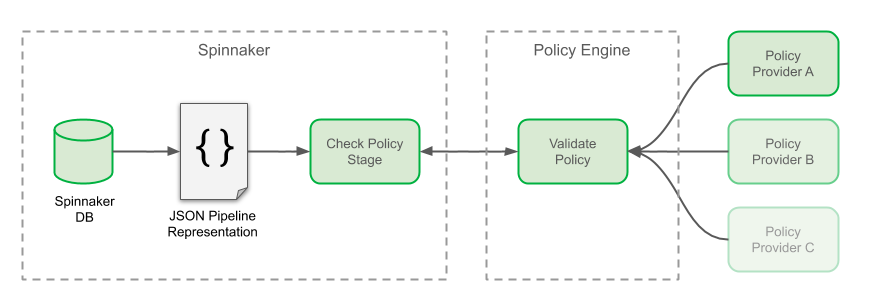

Before releasing the lock, release notes are generated to inform engineers of the delta of changes between the version they just released and the one currently running in production. Once the lock is released, the stage “Check Policies” verifies that the parameters and variable of the deployment obeys a specific set of criteria, for example: if its service metadata is up-to-date in our service inventory, or if the base image used during deployment is sufficiently recent.

Here’s how the policy stage, the engine, and the providers interact with each other:

In Spinnaker, each event of a pipeline’s execution updates the pipeline’s state in the database. The current state of the pipeline can be fetched by its API as a single JSON document, describing all information related to its execution: including its parameters, the contextual information related to each stage or even the response from the various interfacing components. The role of our “Policy Check” stage is to query this JSON representation of the pipeline, to extract and transform the variables which are forwarded to our policy engine for validation. Our policy engine gathers judgements passed by different policy providers. If the validation by the policy engine fails, the deployment is not rolled back this time; however, promotion to production is not possible and the pipeline is immediately terminated.

The journey through staging deployment finally ends with the stage “Register Deployment”. This stage registers that a successful deployment was made in our staging environment as an artefact. Similarly to the policy check above, certain parameters of the deployment are picked up and consolidated into this document. We use this kind of artefact as proof for upcoming production deployment.

Continuing Our Journey to Engineering Efficiency

With the advancements made in continuous integration and deployment to staging, Conveyor has reduced the efforts needed by our engineers to just three clicks in its interface, when automated deployment is used. Even when the deployment is triggered manually, Conveyor gives the assurance that the parameters selected are valid and it does away with copy/pasting and human interactions across heterogeneous tools.

In the sequel to this blog post, we’ll dive into the improvements that we’ve made to our production deployments and introduce a crucial concept that led to the creation of our proof for successful staging deployment. Finally, we’ll cover the impact that Conveyor had on the continuous delivery of our backend services, by comparing our deployment velocity when we started two years ago versus where we are today.

All these improvements in efficiency for our engineers would never have been possible without the hard work of all team members involved in the project, past and present: Evan Sebastian, Tanun Chalermsinsuwan, Aufar Gilbran, Deepak Ramakrishnaiah, Repon Kumar Roy (Kowshik), Su Han, Voislav Dimitrijevikj, Qijia Wang, Oscar Ng, Jacob Sunny, Subhodip Mandal, and many others who have contributed and collaborated with them.

Join us

Grab is a leading superapp in Southeast Asia, providing everyday services that matter to consumers. More than just a ride-hailing and food delivery app, Grab offers a wide range of on-demand services in the region, including mobility, food, package and grocery delivery services, mobile payments, and financial services across over 400 cities in eight countries.

Powered by technology and driven by heart, our mission is to drive Southeast Asia forward by creating economic empowerment for everyone. If this mission speaks to you, join our team today!