Data Science

Data Science

The Data and Science Behind GrabShare Part I: Verifying Potential and Developing the Algorithm

Launching GrabShare was no easy feat. After reviewing the academic literature, we decided to take a different approach and build a new matching algorithm from the ground up. Not only did this really test our knowledge of fundamental data science principles, but it challenged our team to work together to develop something we had never seen before!

Because we had so much fun learning and developing GrabShare, we wanted to write a two part blog post to share with you what we did and how we did it. After reading this, we hope that you might be more prepared to build your very own optimised [practical, effective and efficient] matching algorithm.

We hope you enjoy the ride!

I. A Little History

By matching different travellers with similar itineraries in both time and their geographic locations, ride-sharing can improve driver utilisation and reduce traffic congestion. This concept of pooling (or called ride-sharing), has been a popular concept for decades due to its significant societal and environmental benefits. Tremendous interest in the real-time or dynamic pooling system has grown in recent years, either from a pooling matching algorithm (e.g., [2], [3]) or a system efficiency perspective [4]. We refer interested readers to [5]–[8] as a comprehensive overview on how optimisation and operations research models in academic literature can support the development of real-time pooling systems and innovative thinking on possible future ride-sharing modes.

Leveraging on an internet-based platform that integrates passengers’ smart-phone data in real-time, we are able to provide a ride-sharing service that allows passengers to spend less while enabling drivers to earn more. Companies such as Didi, Grab, Lyft and Uber have managed to transform the concept of a real-time pooling service from imagination into reality. Even though the problem of how to match drivers and riders in real-time has been extensively studied by various optimisation technologies in literature (e.g., Avego’s ride-sharing system [5] and Lyft match making [9]), there has been a renewed interest in the problem and how we can solve it in practice.

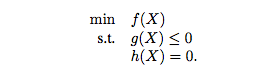

Let us turn the clock back to late 2015. This was when Grab’s Data Science (Optimisation) team was born. The team decided to eschew the literature and current state of the art, and challenged ourselves to design the GrabShare matching algorithm from the ground up, from basic principles. Indeed, its main task was to make ride matching decisions (which is combinatorial) in order to maximise the overall system efficiency, while satisfying specific constraints to guarantee good user experience (such as detour, overlap, trip angle, and efficiency). A general optimisation problem comprises of three main parts: Objective function, Constraints, and Decision Space. The constrained optimisation problem takes the usual form:

Here X denotes a set of decision variables that correspond to real-world decisions we can adjust or control. The objective function f(X) is either a cost function that we want to minimise, or a value function that we want to maximise. The constraints are mathematical expressions of physical restrictions to decision variables on the possible solutions, which could have either inequality form: g(X) or equality form: h(X) or both.

In this article, we discuss how the GrabShare matching algorithm is tackled as an optimisation problem and how its various formulations can have a different impact to Grab, passengers, and drivers. Differing from previous studies in literature, which mainly focus on improving overall system efficiency using conventional operations research methods, we approached the problem from a more data-driven perspective. Our key focus was on extracting critical insights from data to improve the GrabShare user experience, from the point of design and development of the matching algorithm and throughout subsequent continual efforts of product improvement.

II. From GrabCar to GrabShare

From 2012 onwards, Grab has had a mature product named “GrabCar” that serves millions of individual traveling requests by an integrated dispatching system. The drivers’ locations and other states are maintained in the system such that we can simultaneously find drivers and make assignments for thousands of traveling requests. With a GPS-enabled mobile device, the users (known as passengers) can use Grab’s passenger app to place transportation requests from specified origin to destination. In this article we use the term “booking” to denote a confirmed transportation request placed by a passenger, which contains explicit pickup and drop-off information. At the same time, drivers who have registered with their own or rented vehicles can login to Grab’s system through a driver app to indicate their readiness to take nearby passengers. The GrabCar service is similar to a traditional taxi service in that a completed GrabCar ride consists of three steps:

-

A passenger makes a booking;

-

A GrabCar driver is assigned to the booking;

-

The assigned driver picks up the passenger and ferries him/her to the destination and the ride is completed.

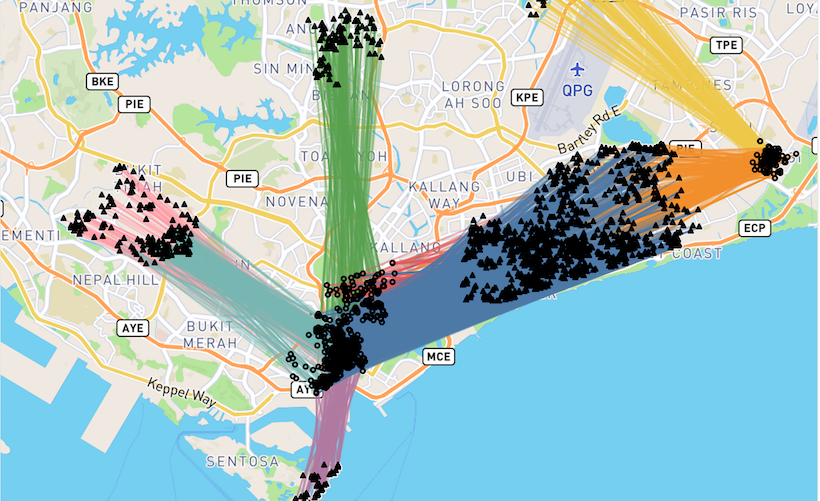

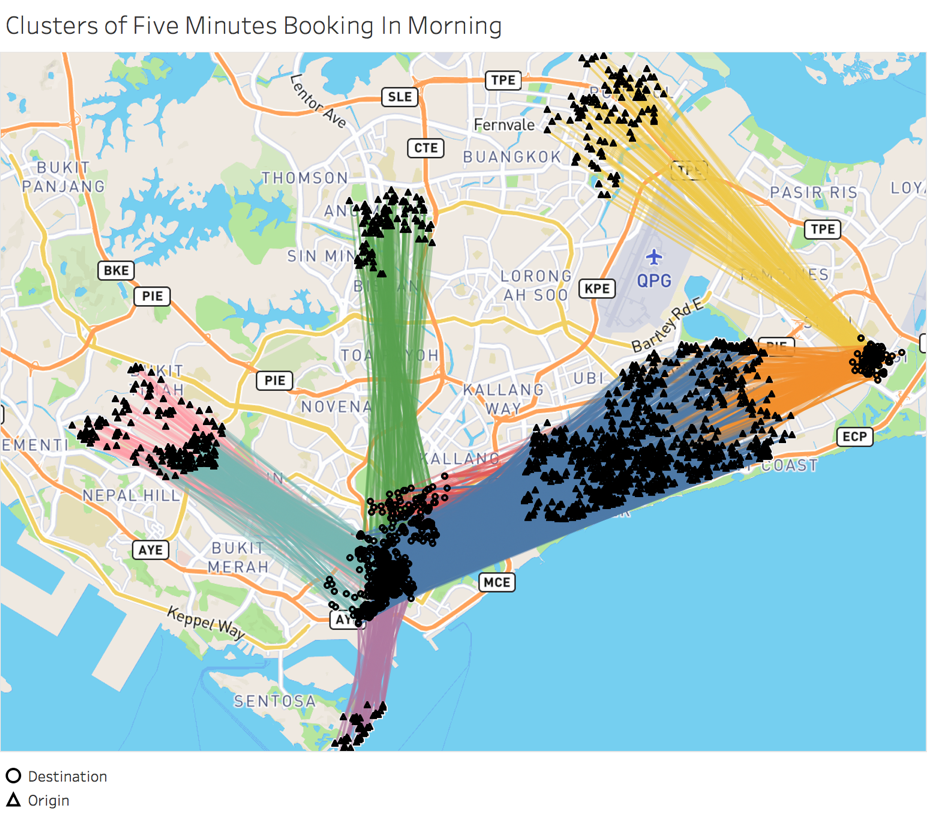

It is common for people to arrange for manual ride-sharing with our friends traveling in the same direction to save on travel cost as well as to socialize and connect during the trip. By making use of real-time integrated ride information in the Grab system, we aimed to automatically match strangers traveling in similar directions and assign the same vehicle to both their journeys, allowing them to effectively car-pool. Before promoting the concept of GrabShare however, we had to verify its potential from the existing GrabCar bookings. For example, during morning peak hours we mappped every single booking into a four-dimensional vector with the latitudes and longitudes of pickup and drop-off locations. In addition, the latitudes and longitudes were transformed into a Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) format to map the earth’s surface to an 2-dimensional Cartesian Coordinate System for distance calculation. After applying a DBSCAN cluster method [10] with parameter “eps=300”, which means that only bookings with distance of less than 300 meters can be considered as neighbourhoods, we observed eight clear clusters of booking with close pickup and drop-off locations in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Morning booking clusters with similar itineraries

Figure 1. Morning booking clusters with similar itineraries

The booking requests within each cluster can be allocated and fulfilled with less vehicles, through pooling. Even though not all of them may be willing to share vehicles with others, at least those with unallocated bookings (around 8%) may benefit. After repeating this analysis for different time periods, we observed that a certain percentage of the bookings could be covered with good performing clusters as seen in Table I. We observed that the coverage rate for different time periods fluctuates from 35% to 45% for most part of the day (coverage during mid-night and early morning hours is much smaller as the amount of bookings is much smaller). Because bookings in the same cluster are “near perfect matches” with very close pickup and drop-off location, the potential for GrabShare was found to be quite promising because we could expect even more opportunities for matching in the middle of a trip.

| Hours | 8-10 | 10-13 | 14-16 | 16-18 | 18-22 | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage | 46% | 39% | 35% | 38% | 43% | 22% |

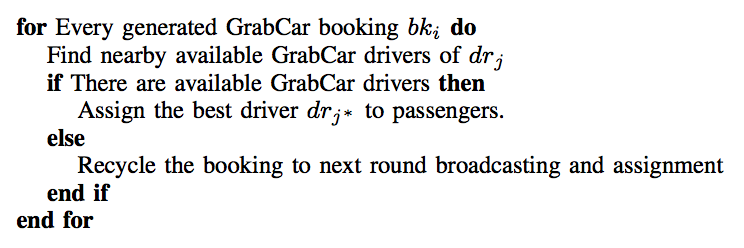

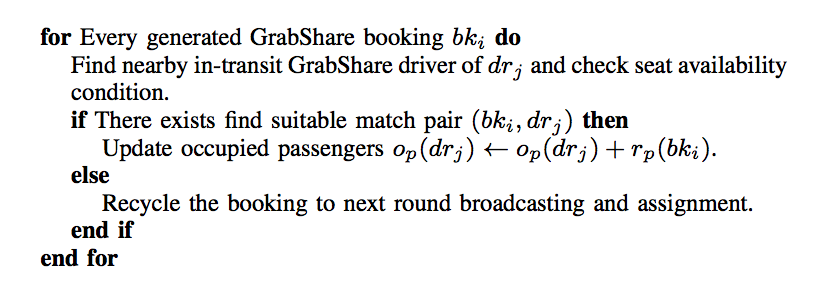

The assignment flow of typical GC bookings is stated in Algorithm I. For every newly arrived booking, we search for nearby drivers and check for their availability condition. If no driver is available, we recycle it to the next round of assignment. Otherwise we select the most suitable driver for them. Leveraging the current system structure, we planned to extend the GrabCar service to GrabShare by maintaining more detailed bookings and driver state information along with an additional check on seat reservation.

Algorithm I. GrabCar booking assignment flow

Algorithm I. GrabCar booking assignment flow

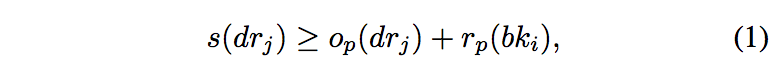

Specifically, Algorithm II gives the assignment flow of Grab- Share bookings. We can see that its overall structure is the same with GrabCar except for two differences. Firstly, the candidate driver set is different. For every new GrabShare booking, we search for in-transit GrabShare drivers who are currently serving at least one GrabShare booking. Therefore, we need to check seat availability condition to ensure that the vehicle has enough remaining seats to serve the new GrabShare booking. Mathematically, the following seat reservation constraint needs to be satisfied for a successful assignment between booking bki and driver drj:

where s(drj) denotes the total capacity of the vehicle drj, op(drj) is one of the maintained variable that denotes the current occupied capacity of the vehicle drj and rp (bki) is the required capacity for booking bki. To make it consistent, we also need to update the vehicle occupied capacity variable op (drj) by adding the booking required capacity rp (bki) after every successful assignment or removing it if cancellation occurs.

Algorithm II. GrabShare booking assignment flow

Algorithm II. GrabShare booking assignment flow

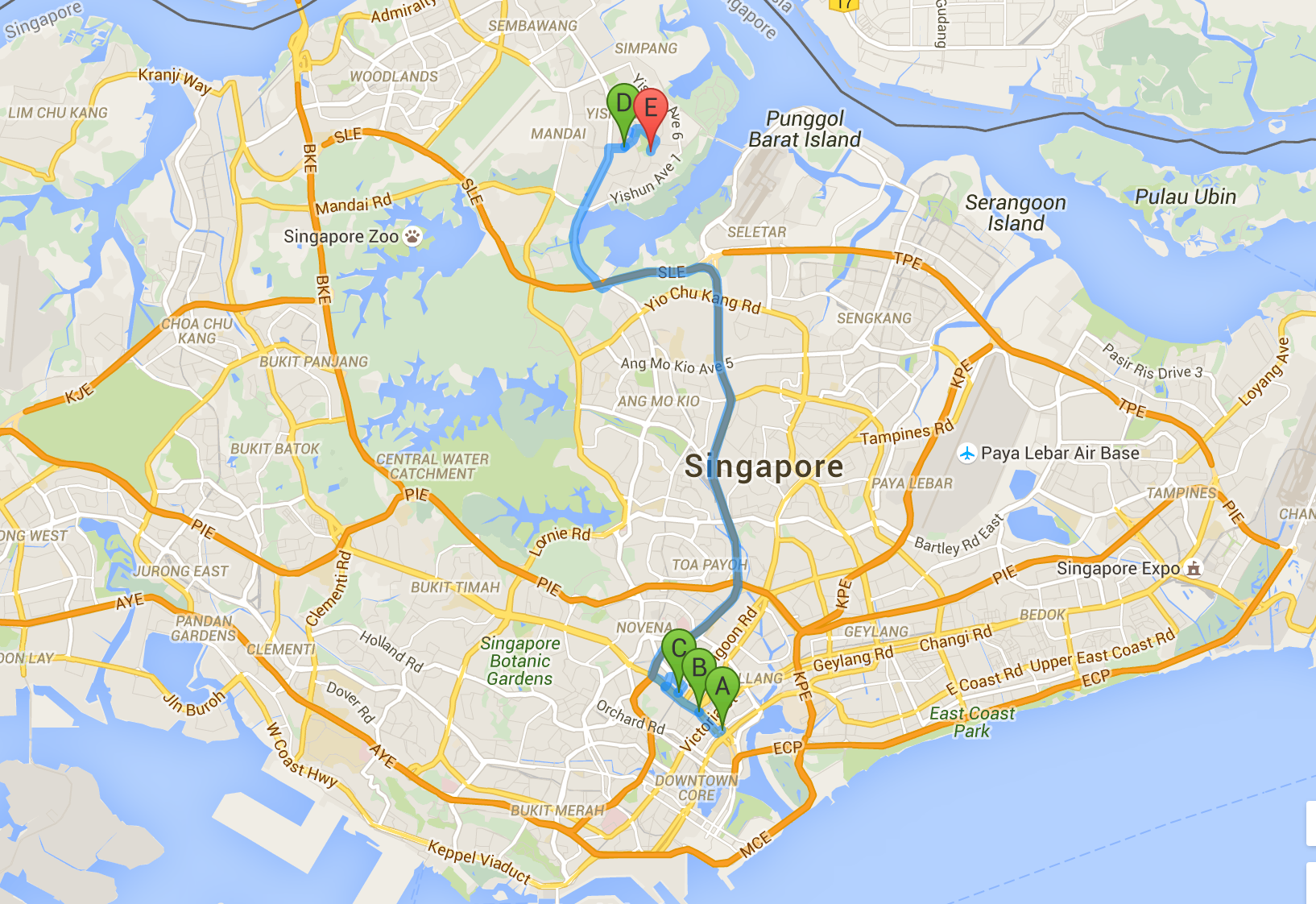

Figure 2. GrabShare match case in Singapore

Figure 2. GrabShare match case in Singapore

Secondly, GrabShare’s user experience is different from GrabCar due to the sharing concept. Here we defined some measures to evaluate the GrabShare matching, taking into consideration the trip angle, eta (short for Expected Time of Arrival), detour and efficiency. These measures are used to exclude unacceptable matches and to quantify how good the match is. For example, given a matching route scenario of two bookings (n = 1) as shown in Figure 2. At the first step the driver receives the first GrabShare booking from point A to D (25 minutes direct trip time). After the driver picks up the first passenger and reaches location B on his way to D, he/she is assigned to pickup the second booking from C to E (21 minutes direct trip time). A GrabShare match happens and the final route sequence is generated as A→B→C→D→E. With pooling, it takes 29.5 minutes for the first passenger and 27 minutes for the second passenger to reach their destinations, respectively. Overall it is a good match as the passengers are only delayed a little bit by pooling with a promising driver utilisation rate. In this case the driver only needs to drive 23.72km in total to serve two bookings, instead of a total of 39.13km if they were served separately. Not only does this allow passengers to be allocated rides, but drivers save considerable time and money through this efficiency, while increasing their earning power simultaneously.

This is ultimately deemed a good match, but the details on how we quantify this and its corresponding optimisation model are explained in Part II.

References

[1] Grab, “Grab extends GrabShare regionally with Malaysia’s first on-demand carpooling service,” 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.grab.com/my/press/business/grabsharemalaysia/

[2] J. Alonso-Mora, S. Samaranayake, A. Wallar, E. Frazzoli, and D. Rus, “On-demand high-capacity ride-sharing via dynamic trip-vehicle assignment,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 114, no. 3, pp. 462–467, Mar 2017.

[3] A. Conner-Simons, “Study: carpooling apps could reduce taxi traffic 75 percent,” 2016. [Online]. Available: http://www.csail.mit.edu/ridesharing_reduces_traffic_300_percent

[4] D. Dimitrijevic, N. Nedic, and V. Dimitrieski, “Real-time carpooling and ride-sharing: Position paper on design concepts, distribution and cloud computing strategies,” in Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), 2013 Federated Conference on. IEEE, 2013, pp. 781–786.

[5] N. Agatz, A. Erera, M. Savelsbergh, and X. Wang, “Optimization for dynamic ride-sharing: A review,” European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 223, no. 2, pp. 295–303, 2012.

[6] A. Amey, J. Attanucci, and R. Mishalani, “Real-time ridesharing: opportunities and challenges in using mobile phone technology to improve rideshare services,” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, no. 2217, pp. 103–110, 2011.

[7] N. D. Chan and S. A. Shaheen, “Ridesharing in north america: Past, present, and future,” Transport Reviews, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 93–112, 2012.

[8] M. Furuhata, M. Dessouky, F. Ordonez, M.-E. Brunet, X. Wang, and S. Koenig, “Ridesharing: The state-of-the-art and future directions,” Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, vol. 57, pp. 28–46, 2013.

[9] Lyft, “Matchmaking in lyft line—part 1,” 2016. [Online]. Available: https://eng.lyft.com/matchmaking-in-lyft-line-9c2635fe62c4

[10] M. Ester, H.-P. Kriegel, J. Sander, X. Xu et al., “A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise.” in Kdd, vol. 96, no. 34, 1996, pp. 226–231.