Engineering

·

Data Science

·

Security

Engineering

·

Data Science

·

Security

Using mobile sensor data to encourage safer driving

“Telematics”, a cross between the words telecommunications and informatics, was coined in the late 1970s to refer to the use of communication technologies in facilitating exchange of information. In the modern day, such technologies may include cloud platforms, mobile networks, and wireless transmissions (e.g., Bluetooth). Although the initial intention is for a more general scope, telematics is now specifically used to refer to vehicle telematics where details of vehicle movements are tracked for use cases such as driving safety, driver profiling, fleet optimisation, and productivity improvements.

We’ve previously published this article to share how Grab uses telematics to improve driver safety. In this blog post, we dive deeper into how telematics technology is used at Grab to encourage safer driving for our driver and delivery partners.

Background

At Grab, the safety of our users and their experience on our platform is our highest priority. By encouraging safer driving habits from our driver and delivery partners, road traffic accidents can be minimised, potentially reducing property damage, injuries, and even fatalities. Safe driving also helps ensure smoother rides and a more pleasant experience for consumers using our platform.

To encourage safer driving, we should:

- Have a data-driven approach to understand how our driver and delivery partners are driving.

- Help partners better understand how to improve their driving by summarising key driving history into a personalised Driving Safety Report.

Understanding driving behaviour

One of the most direct forms of driving assessment is consumer feedback or complaints. However, the frequency and coverage of this feedback is not very high as they are only applicable to transport verticals like JustGrab or GrabBike and not delivery verticals like GrabFood or GrabExpress. Plus, most driver partners tend not to receive any driving-related feedback (whether positive or negative), even for the transport verticals.

A more comprehensive method of assessing driving behaviour is to use the driving data collected during Grab bookings. To make sense of these data, we focus on selected driving manoeuvres (e.g., braking, acceleration, cornering, speeding) and detect the number of instances where our data shows unsafe driving in each of these areas.

We acknowledge that the detected instances may be subjected to errors and may not provide the complete picture of what’s happening on the ground (e.g., partners may be forced to do an emergency brake due to someone swerving into their lane).

To address this, we have incorporated several fail-safe checks into our detection logic to minimise erroneous detection. Also, any assessment of driving behaviour will be based on an aggregation of these unsafe driving instances over a large amount of driving data. For example, individual harsh braking instances may be inconclusive but if a driver partner displays multiple counts consistently across many bookings, it is likely that the partner may be used to unsafe driving practices like tailgating or is distracted while driving.

Telematics for detecting unsafe driving

For Grab to consistently ensure our consumers’ safety, we need to proactively detect unsafe driving behaviour before an accident occurs. However, it is not feasible for someone to be with our driver and delivery partners all the time to observe their driving behaviour. We should leverage sensor data to monitor these driving behaviour at scale.

Traditionally, a specialised “black box” inertial measurement unit (IMU) equipped with sensors such as accelerometers, gyroscopes, and GPS needs to be installed in alignment with the vehicle to directly measure vehicular acceleration and speed. In this manner, it would be straightforward to detect unsafe driving instances using this data. Unfortunately, the cost of purchasing and installing such devices for all our partners is prohibitively high and it would be hard to scale.

Instead, we can leverage a device that all partners already have: their mobile phone. Modern smartphones already contain similar sensors to those in IMUs and data can be collected through the telematics SDK. More details on telematics data collection can be found in a recently published Grab tech blog article1.

It’s important to note that telematics data are collected at a sufficiently high sampling frequency (much more than 1 Hz) to minimise inaccuracies in detecting unsafe driving instances characterised by sharp acceleration impulses.

Processing mobile sensor data to detect unsafe driving

Unlike specialised IMUs installed in vehicles, mobile sensor data have added challenges to detecting unsafe driving.

Accounting for orientation: Phone vs. vehicle

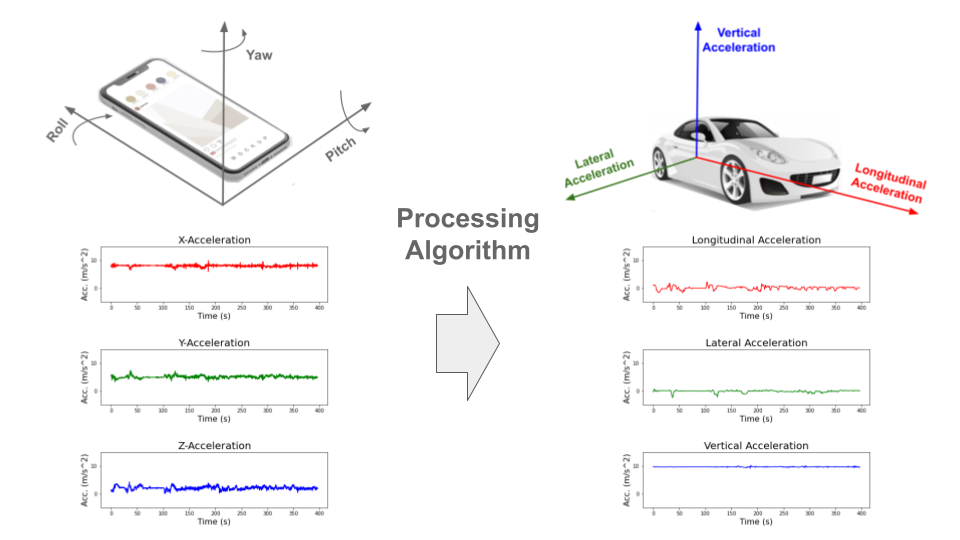

The phone is usually in a different orientation compared to the vehicle. Strictly speaking, the phone accelerometer sensor measures the accelerations of the phone and not the vehicle acceleration. To infer vehicle acceleration from phone sensor data, we developed a customised processing algorithm optimised specifically for Grab’s data.

First, the orientation offset of the phone with respect to the vehicle is defined using Euler angles: roll, pitch and yaw. In data windows with no net acceleration of the vehicle (e.g., no braking, turning motion), the only acceleration measured by the accelerometer is gravitational acceleration. Roll and pitch angles can then be determined through trigonometric manipulation. The complete triaxial accelerations of the phone are then rotated to the horizontal plane and the yaw angle is determined by principal component analysis (PCA).

An assumption here is that there will be sufficient braking and acceleration manoeuvring for PCA to determine the correct forward direction. This Euler angles determination is done periodically to account for any movement of phones during the trip. Finally, the raw phone accelerations are rotated to the vehicle orientation through a matrix multiplication with the rotation matrix derived from the Euler angles (see Figure 1).

Handling variations in data quality

Our processing algorithm is optimised to be highly robust and handle large variations in data quality that is expected from bookings on the Grab platform. There are many reported methods for processing mobile data to reorientate telematics data for four wheel vehicles23.

However, with the prevalent use of motorcycles on our platform, especially for delivery verticals, we observed that data collected from two wheel vehicles tend to be noisier due to differences in phone stability and vehicular vibrations. Data noise can be exacerbated if partners hold the phone in their hand or place it in their pockets while driving.

In addition, we also expect a wide variation in data quality and sensor availability from different phone models, such as older, low-end models to the newest, flagship models. A good example to illustrate the robustness of our algorithm is having different strategies to handle different degrees of data noise. For example, a simple low-pass filter is used for low noise data, while more complex variational decomposition and Kalman filter approaches are used for high noise data.

Detecting behaviour anomalies with thresholds

Once the vehicular accelerations are inferred, we can use a thresholding approach (see Figure 2) to detect unsafe driving instances.

For unsafe acceleration and braking, a peak finding algorithm is used to detect acceleration peaks beyond a threshold in the longitudinal (forward/backward) direction. For unsafe cornering, older and lower end phones are usually not equipped with gyroscope sensors, so we should look for peaks of lateral (sidewards) acceleration (which constitutes the centripetal acceleration during the turn) beyond a threshold. GPS bearing data that coarsely measures the orientation of the vehicle is then used to confirm that a cornering and not lane change instance is being detected. The thresholds selected are fine-tuned on Grab’s data using initial values based on published literature4 and other sources.

To reduce false positive detection, no unsafe driving instances will be flagged when:

- Large discrepancies are observed between speeds derived from integrating the longitudinal (forward/backward) acceleration and speeds directly measured by the GPS sensor.

- Large phone motions are detected. For example, when the phone falls to the seat from the dashboard, accelerations recorded on the phone sensor will deviate significantly from the vehicle accelerations.

- GPS speed is very low before and after the unsafe driving instance is detected. This is limited to data collected from motorcycles which is usually used by delivery partners. It implies that the partner is walking and not in a vehicle. For example, a GrabFood delivery partner may be collecting the food from the merchant partner on foot, so no unsafe driving instances should be detected.

Detecting speeding instances from GPS speeds and map data

To define speeding along a stretch of road, we used a rule-based method by comparing raw speeds from GPS pings with speeding thresholds for that road. Although GPS speeds are generally accurate (subjected to minimal GPS errors), we need to take more precautions to ensure the right speeding thresholds are determined.

These thresholds are set using known speed limits from available map data or hourly aggregated speed statistics where speed limits are not available. The coverage and accuracy of known speed limits is continuously being improved by our in-house mapping initiatives and validated comprehensively by the respective local ground teams in selected cities.

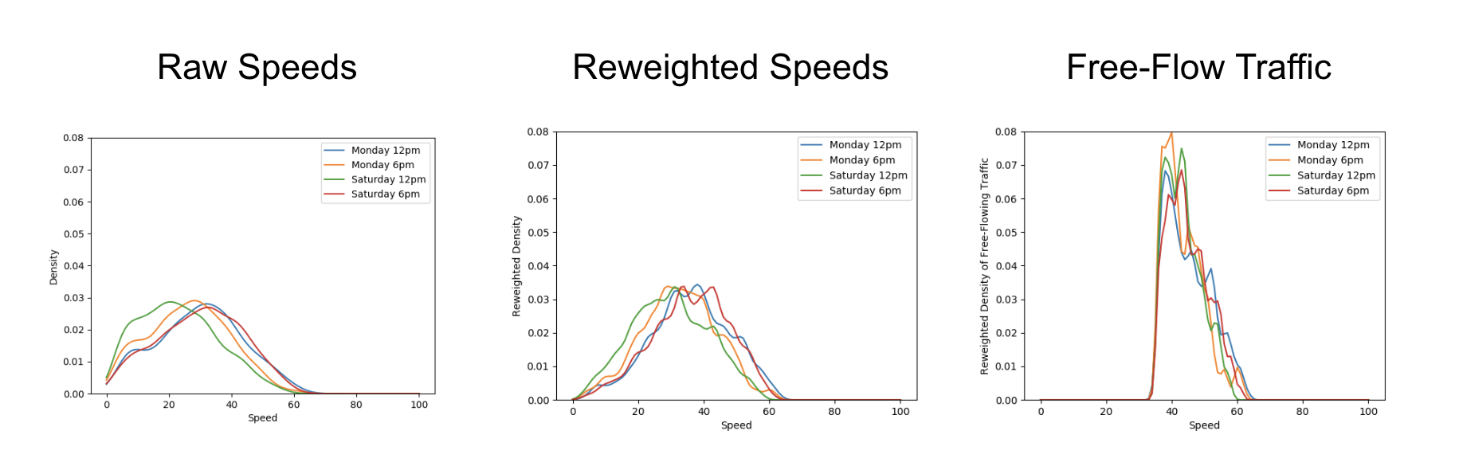

Aggregating GPS pings from Grab driver and delivery partners can be a helpful proxy to actual speed limits by defining speeding violations as outliers from socially acceptable speeds derived from partners collectively. To reliably compute aggregated speed statistics, a representative speed profile for each stretch of road must first be inferred from raw GPS pings (see Figure 3).

As ping sampling intervals are fixed, more pings tend to be recorded for slower speeds. To correct the bias in the speed profile, we reweigh ping counts by using speed values as weights. Furthermore, to minimise distortions in the speed profile from vehicles driving at lower-than-expected speeds due to high traffic volumes, only pings from free-flowing traffic are used when inferring the speed profile.

Free-flowing traffic is defined by speeds higher than the median speed on each defined road category (e.g., small residential roads, normal primary roads, large expressways). To ensure extremely high speeds are flagged regardless of the speed of other drivers, maximum threshold values for aggregated speeds are set for each road category using heuristics based on the maximum known speed limit of that road category.

Besides a representative speed profile, hourly aggregation should also include data from a sufficient number of unique drivers depending on speed variability. To obtain enough data, hourly aggregations are performed on the same day of the week over multiple weeks. This way, we have a comprehensive time-specific speed profile that accounts for traffic quality (e.g., peak hour traffic, traffic differences between weekdays/weekends) and driving conditions (e.g., visibility difference between day/night).

When detecting speeding violations, the GPS pings used are snapped-to-road and stationary pings, pings with unrealistic speeds, while pings with low GPS accuracy (e.g., when the vehicle is in a tunnel) are excluded. A speeding violation is defined as a sequence of consecutive GPS pings that exceed the speeding threshold. The following checks were put in place to minimise erroneous flagging of speeding violations:

- Removal of duplicated (or stale) GPS pings.

- Sufficient speed buffer given to take into account GPS errors.

- Sustained speeding for a prolonged period of time is required to exclude transient speeding events (e.g., during lane change).

Driving safety report

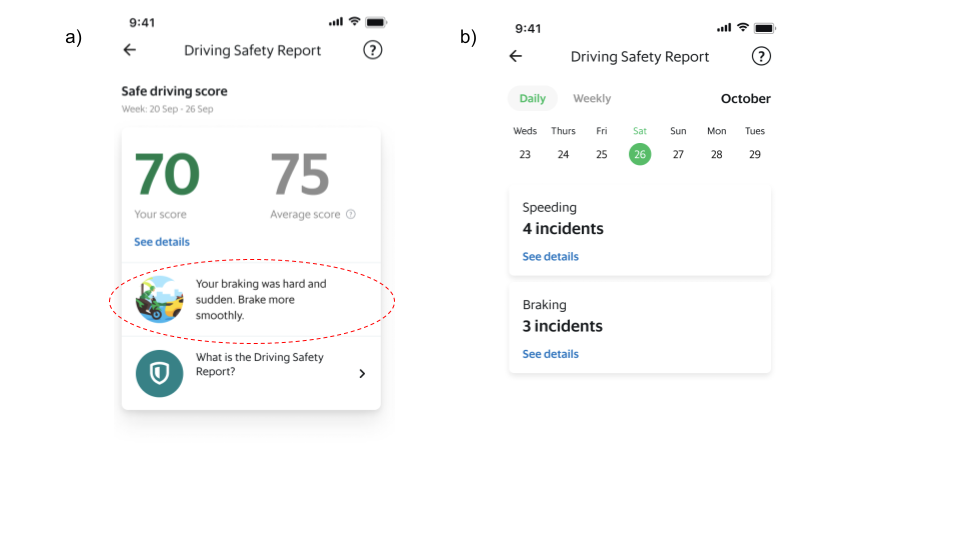

The driving safety report is a platform safety product that driver and delivery partners can access via their driver profile page on the Grab Driver Application (see Figure 4). It is updated daily and aims to create awareness regarding driving habits by summarising key information from the processed data into a personalised report that can be easily consumed.

Individual reports of each driving manoeuvre (e.g., braking, acceleration, cornering and speeding) are available for daily and weekly views. Partners can also get more detailed information of each individual instance such as when these unsafe driving instances were detected.

Actionable insights

Besides compiling the instances of unsafe driving in a report to create awareness, we are also using these data to provide some actionable recommendations for our partners to improve their driving.

With unsafe driving feedback from consumers and reported road traffic accident data from our platform, we also train machine learning models to identify patterns in the detected unsafe driving instances and estimate the likelihood of partners receiving unsafe driving feedback or getting into accidents. One use case is to compute a safe driving score that equates a four-wheel partner’s driving behaviour to a numerical value where a higher score indicates a safer driver.

Additionally, we use Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) approaches to determine which driving manoeuvre contributes the most to increasing the likelihood of partners receiving unsafe driving feedback or getting into accidents. This information is included as an actionable insight in the driving safety report and helps partners to identify the key area to improve their driving.

What’s next?

At the moment, Grab performs telematics processing and unsafe driving detections after the trip and updates the report the next day. One of the biggest improvements would be to share this information with partners faster. We are actively working on developing a real-time processing algorithm that addresses this and also, satisfies the robustness requirements such that partners are immediately aware after an unsafe driving instance is detected.

Besides detecting typical unsafe driving manoeuvres, we are also exploring other use cases for mobile sensor data in road safety such as detection of poor road conditions, counterflow driving against traffic, and phone usage leading to distracted driving.

Join us

Grab is the leading superapp platform in Southeast Asia, providing everyday services that matter to consumers. More than just a ride-hailing and food delivery app, Grab offers a wide range of on-demand services in the region, including mobility, food, package and grocery delivery services, mobile payments, and financial services across 428 cities in eight countries.

Powered by technology and driven by heart, our mission is to drive Southeast Asia forward by creating economic empowerment for everyone. If this mission speaks to you, join our team today!

References

-

Burhan, W. (2022). How telematics helps Grab to improve safety. Grab Tech Blog. https://engineering.grab.com/telematics-at-grab ↩

-

Mohan, P., Padmanabhan, V.N. and Ramjee, R. (2008).Nericell: rich monitoring of road and traffic conditions using mobile smartphones. SenSys ‘08: Proceedings of the 6th ACM conference on Embedded network sensor systems, 312-336. https://doi.org/10.1145/1460412.1460444 ↩

-

Sentiance (2016). Driving behavior modeling using smart phone sensor data. Sentiance Blog. https://sentiance.com/2016/02/11/driving-behavior-modeling-using-smart-phone-sensor-data/ ↩

-

Yarlagadda, J. and Pawar, D.S. (2022). Heterogeneity in the Driver Behavior: An Exploratory Study Using Real-Time Driving Data. Journal of Advanced Transportation. vol. 2022, Article ID 4509071. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4509071 ↩