Engineering

Engineering

This Rocket Ain't Stopping - Achieving Zero Downtime for Rails to Golang API Migration

Grab has been transitioning from a Rails + NodeJS stack to a full Golang Service Oriented Architecture. To contribute to a single common code base, we wanted to transfer engineers working on the Rails server powering our passenger app APIs to other Go teams.

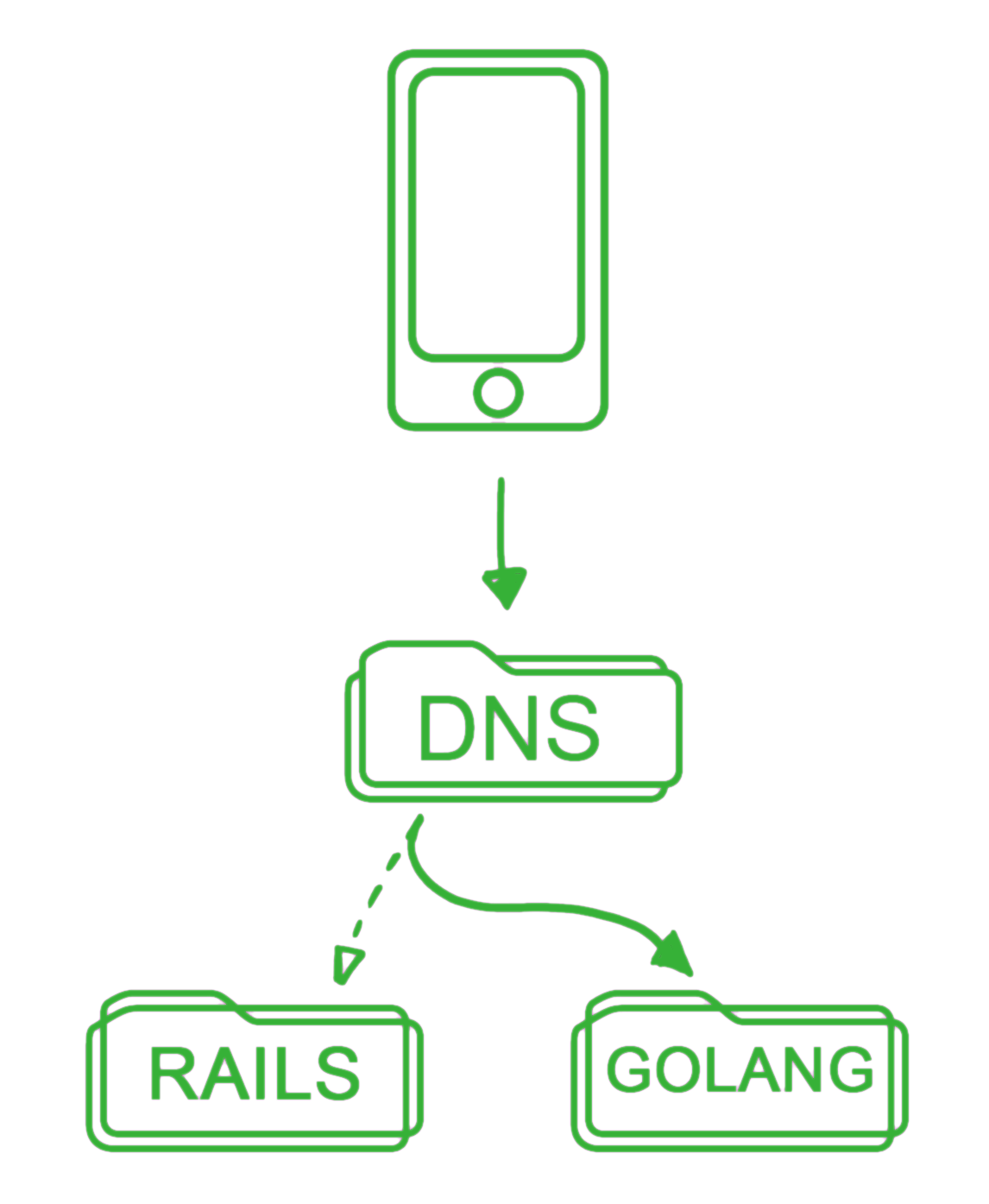

To do this, a newly formed API team was given the responsibility of carefully migrating the public passenger app APIs from the existing Rails app to a new Go server. Our goal was to have the public API hostname DNS point to the new Go server cluster.

Since the API endpoints are live and accepting requests, we developed some rules to maintain optimum stability for the service:

-

Endpoints have to pass a few tests before being deployed:

a. Rigorous unit tests

b. Load tests using predicted traffic based on data from production environment

c. Staging environment QA testing

d. Production environment shadow testing

- Deploying migrated endpoints has to be done one by one

- Deploying of each endpoint needs to be progressive

- In the event of unforeseen bugs, all deployments must be instantly rolled back

We divided the migration work for each endpoint into the following phases:

- Logic migration

- Load testing

- Shadow testing

- Roll out

Logic Migration

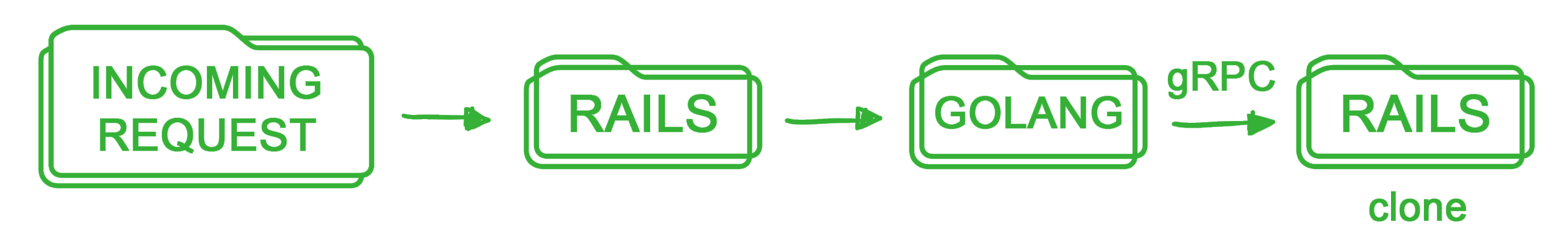

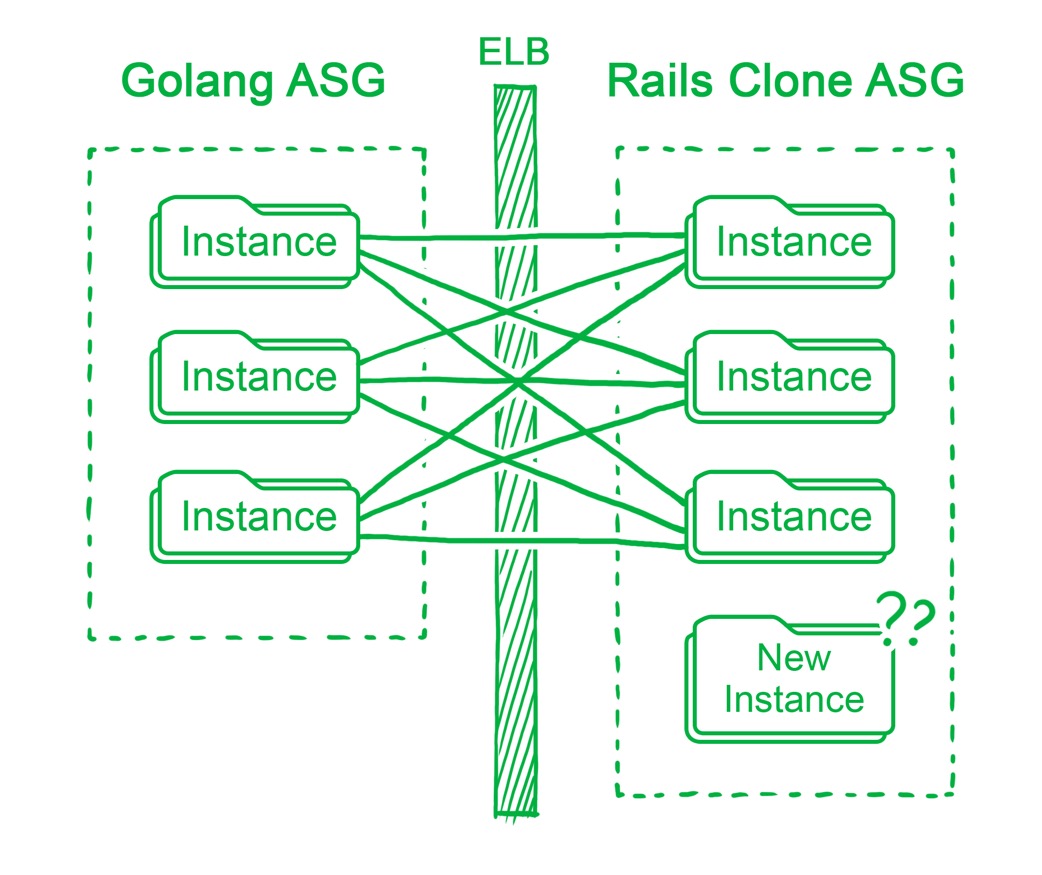

Our initial plan was to enforce a rapid takeover of the Rails server DNS, before porting the logic. To do that, we would clone the existing Rails repository and have the new Go server provide a thin layer proxy, which resembles this in practice:

Problems with Clone Proxy

A key concern for us was the tripling of the HTTP request redirects for each endpoint. Entry into the Go server had to remain HTTP, as it needed to takeover the DNS. However, we recognise it was wasteful to have another HTTP entry at the Rails clone.

gRPC was implemented between the Go server and Rails clone to optimise latency. As gRPC runs on HTTP/2 which our Elastic Load Balancer (ELB) did not support, we had to configure the ELB to carry out TCP balancing instead. TCP connections, being persistent, caused a load imbalance amongst our Rails clone instances whenever there was an Auto Scaling Group (ASG) scale event.

We identified 2 ways to solve this.

The first was to implement service discovery into our gRPC setup, either by Zookeeper or etcd for client side load balancing. The second, which we adopted and deemed the easier way albeit more hackish, was to have a script slowly restart all the Go instances every time there was an ASG scaling event on the Rails Clone cluster to force a redistribution of connections. It may seem unwieldy, but it got the job done without distracting our team further.

Grab API team then discovered that the gRPC RubyGem we were using in our Rails clone server had a memory leak issue. It required us to create a rake task to periodically restart the instances when memory usage reached a certain threshold. Our engineers went through the RubyGem’s C++ code and submitted a pull request to get it fixed.

The memory leak problem was then followed by yet another. We noticed mysterious latency mismatches between the Rails clone processes, and the ones measured on the Go server.

At this point, we realised no matter how focused and determined we were at identifying and solving all issues, it was a better use of engineering resources to start work on implementing the logic migration. We threw the month-long gRPC work out the window and started with porting over the Rails server logic.

Interestingly, converting Ruby code to Go did not pose many issues, although we did have to implement several RubyGems in Go. We also took the opportunity to extract modules from the Rails server into separate services, which allowed for maintenance distribution for the various business logic components to separate engineering teams.

Load Testing

Before receiving actual real world traffic, our team performed load testing by dumping all the day logs with the highest traffic in the past month. We proceeded to create a script that would parse the logs and send actual HTTP requests to our endpoint hosted on our staging servers. This ensured that our configurations were adequate for every anticipated traffic, and to verify that our new endpoints were maintaining the Service Level Agreement (SLA).

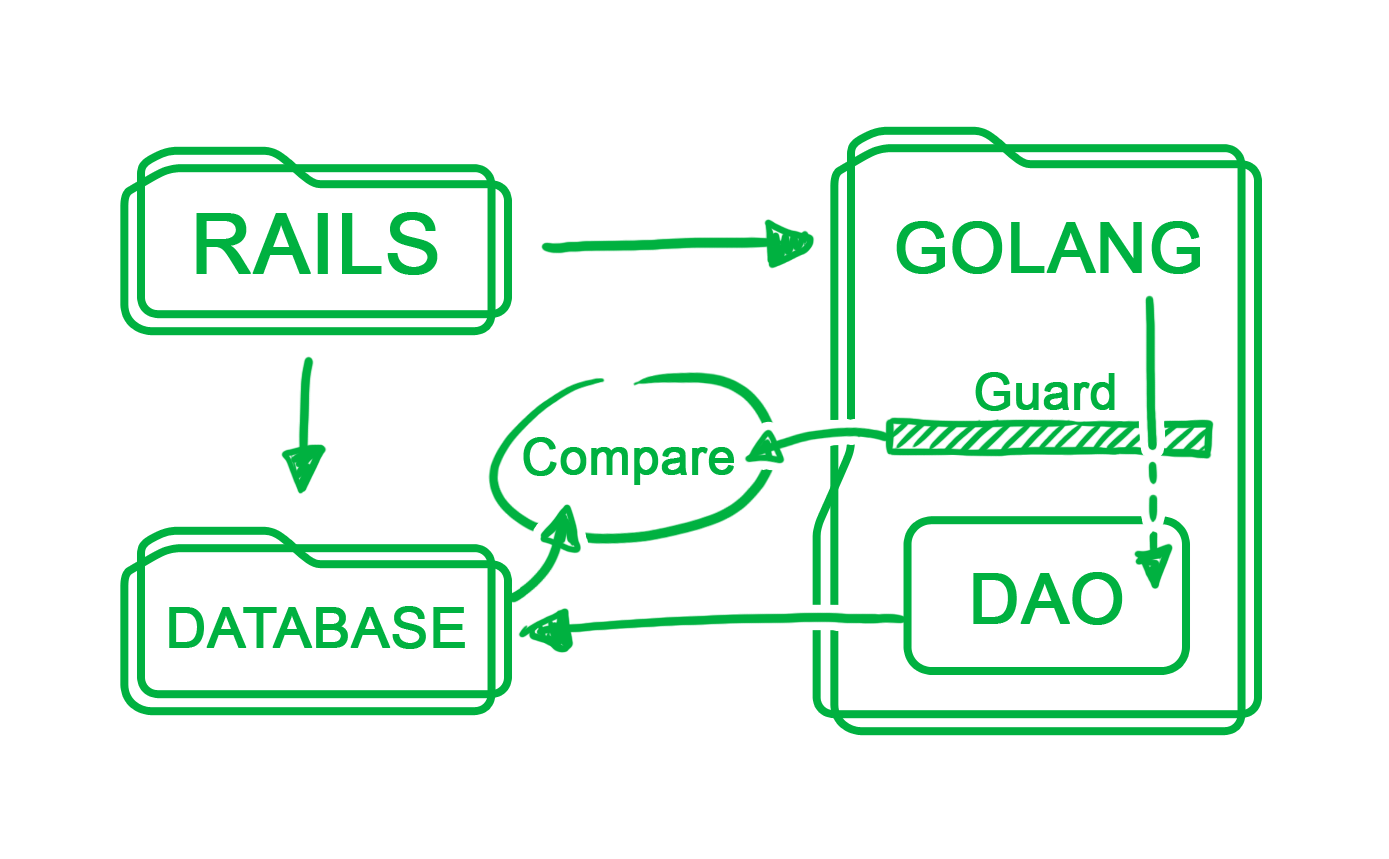

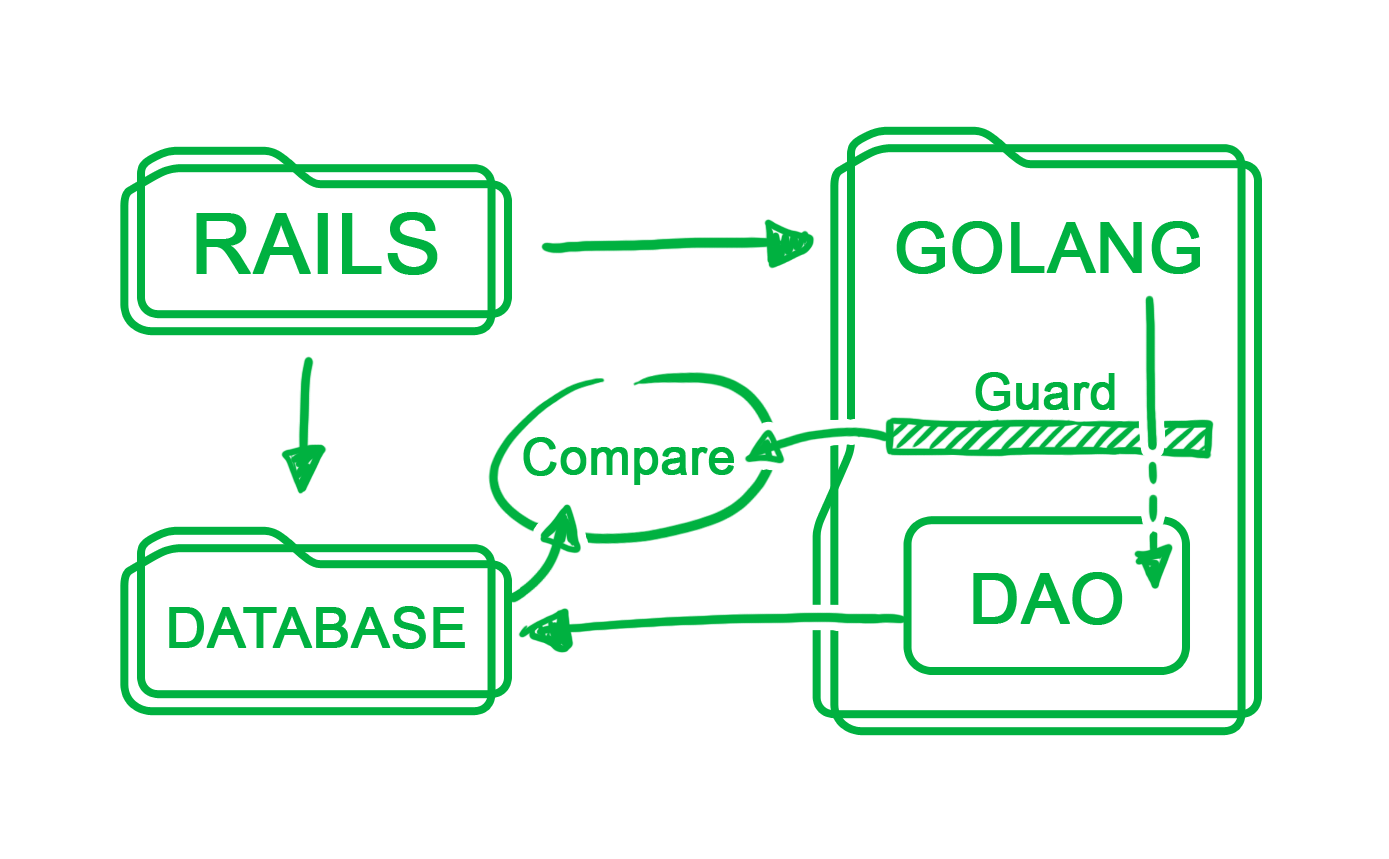

Shadow Testing

Shadowing involves accepting real-time requests to our endpoints for actual load and logic testing. The Go server is as good as live, but does not return any response to the passenger app. The Rails server processes the requests and responses as usual, but it also sends a copy of the request and response to the Go server. The Go server then process the request and compare the resulting responses. This test was carried out on both staging and production environments.

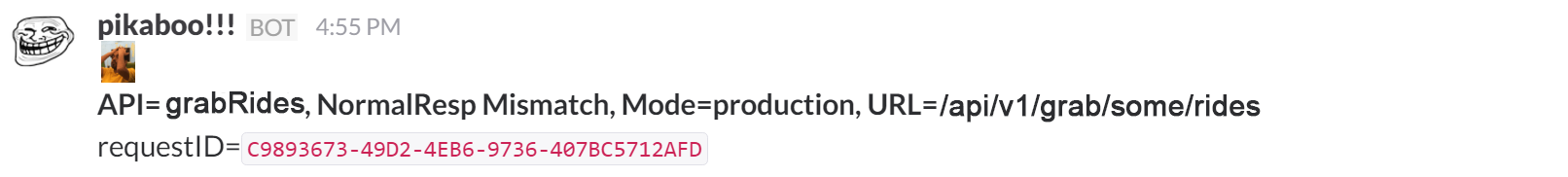

One of our engineers wrote a JSON tokenizer to carry out response comparison, which we used to track any mismatches. All mismatched data was sent to both our statsd server and Slack to alert us of potential migration logic issues.

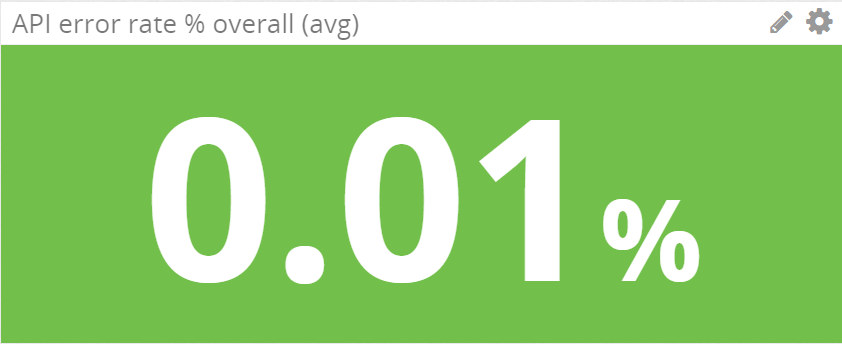

Statsd error rate tracking on DataDog

Statsd error rate tracking on DataDog

Slack pikabot mismatch notification

Slack pikabot mismatch notification

Idempotency During Shadow

It was easy to shadow GET requests due to its idempotent nature in our system. However, we could not simply carry out the same process when we were shadowing PUT/POST/DELETE requests, as it would result in double data writes.

We overcame this by wrapping our data access objects with a layer of mock code. Instead of writing to database, it generates the expected outcome of the database row before comparing with the actual row in the database.

As the shadowing process occurs only after the Rails server has processed the request, we knew database changes existed. Clearly, the booking states may have changed between the Rails processing time and the Go shadow juncture, resulting in a mismatch. For such situations, the occurrence rate was low enough that we could manually debug and verify.

Progressive Shadowing

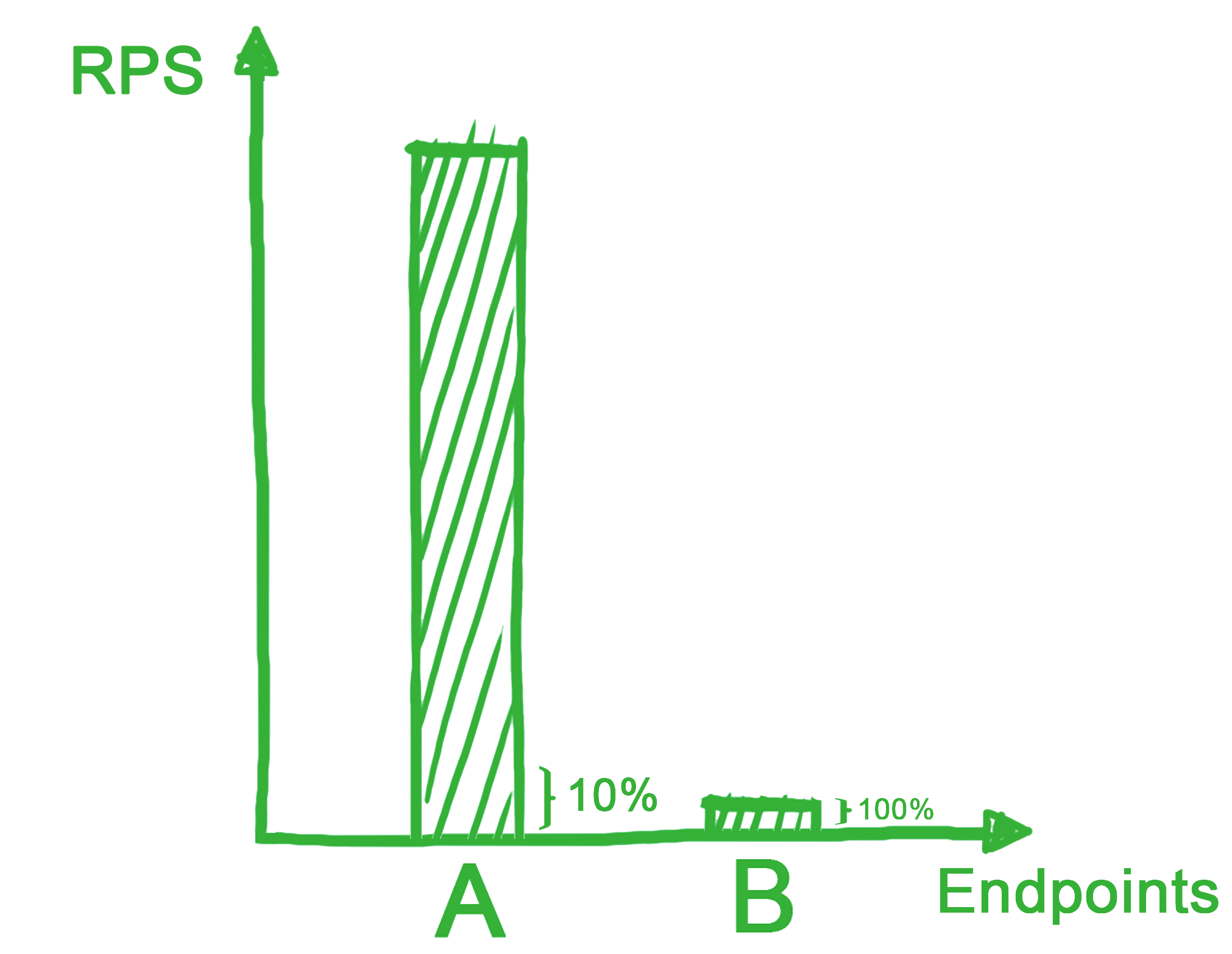

The shadowing process affects the number of outgoing connections the Rails server can make. We therefore had to ensure that we could control the gradual increase in shadow traffic. Code was implemented in the Rails server to check our configuration Redis for how much we would like to shadow, and then throttle the redirection accordingly. Percentage increments seemed intuitive to us at first, but we learnt our mistake the hard way when one of our ELBs started terminating requests due to spillovers.

As exemplified by the illustration above, one of our endpoints had such a huge number of requests that a mere single percent of its requests dwarfed the full load of 5 others combined. Percentages meant nothing without load context. We mitigated the issue when we switched to increments by requests per second (RPS).

Prewarming ELB

In addition to switching to RPS increments, we notified AWS Support in advance to prewarm our ELBs. Although the operations of the ELB are within a black box, we can assume that it is built using proprietary scaling groups of Elastic Cloud Compute (EC2) instances. These instances are most likely configured with the following parameters:

a. Connection count (network interface)

b. Network throughput (memory and CPU)

c. Scaling speed (more instances vs. larger instance hardware)

This will provide more leeway in increasing RPS during shadow or roll out.

Roll Out

Similar to shadowing endpoints, it was necessary to roll out discrete endpoints with traffic control. Simply changing DNS for roll out would require the migrated Go API server to be coded, tested and configured with perfect foresight to instantly take over 100% traffic of all passenger app requests across all 30 over endpoints. By adopting the same method used in shadowing, we could turn on a single endpoint at the RPS we want. The Go server will then be able to gradually take over the traffic before the final DNS switch.

Final Words

We hope this post will be useful for those planning to undertake migrations with similar scale and reliability requirements. If this type of challenges interest you, join our Engineering team!