Engineering

Engineering

Sliding window rate limits in distributed systems

Like many other companies, Grab uses marketing communications to notify users of promotions or other news. If a user receives these notifications from multiple companies, it would be a form of information overload and they might even start considering these communications as spam. Over time, this could lead to some users revoking their consent to receive marketing communications altogether. Hence, it is important to find a rate-limited solution that sends the right amount of communications to our users.

Background

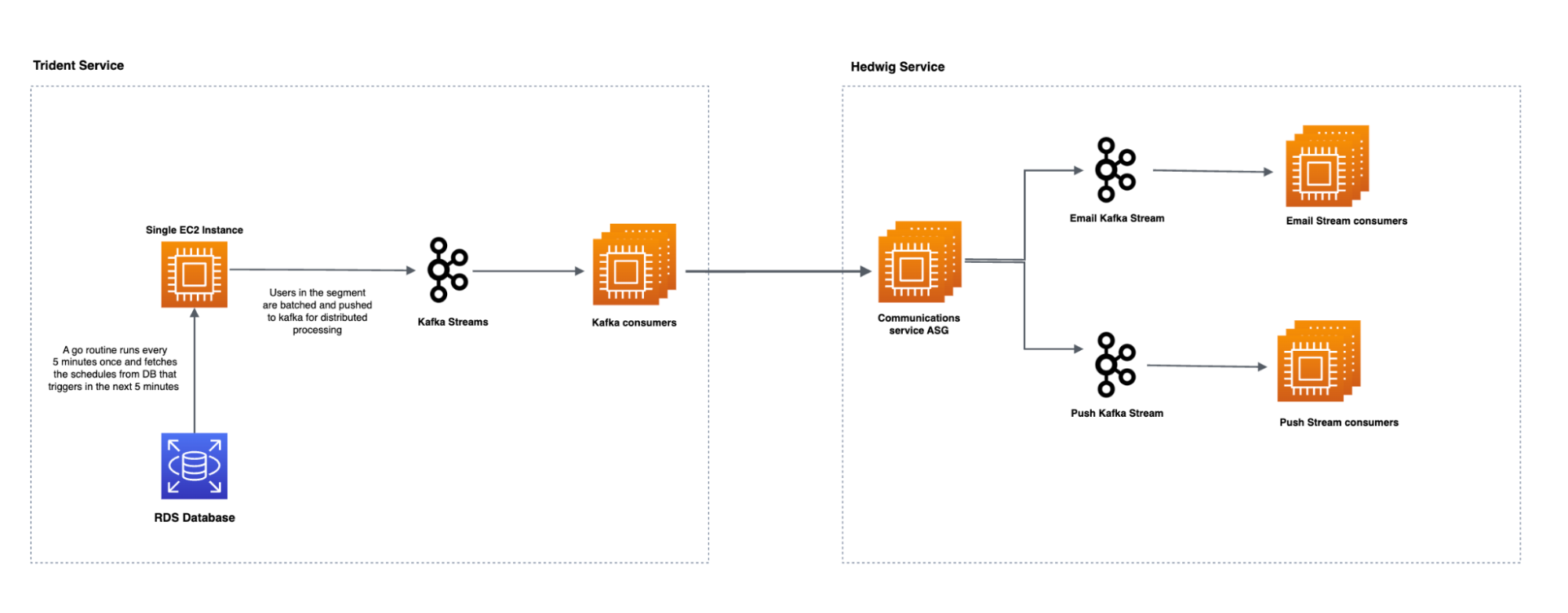

In Grab, marketing emails and push notifications are part of carefully designed campaigns to ensure that users get the right notifications (i.e. based on past orders or usage patterns). Trident is Grab’s in-house tool to compose these campaigns so that they run efficiently at scale. An example of a campaign is scheduling a marketing email blast to 10 million users at 4 pm. Read more about Trident’s architecture here.

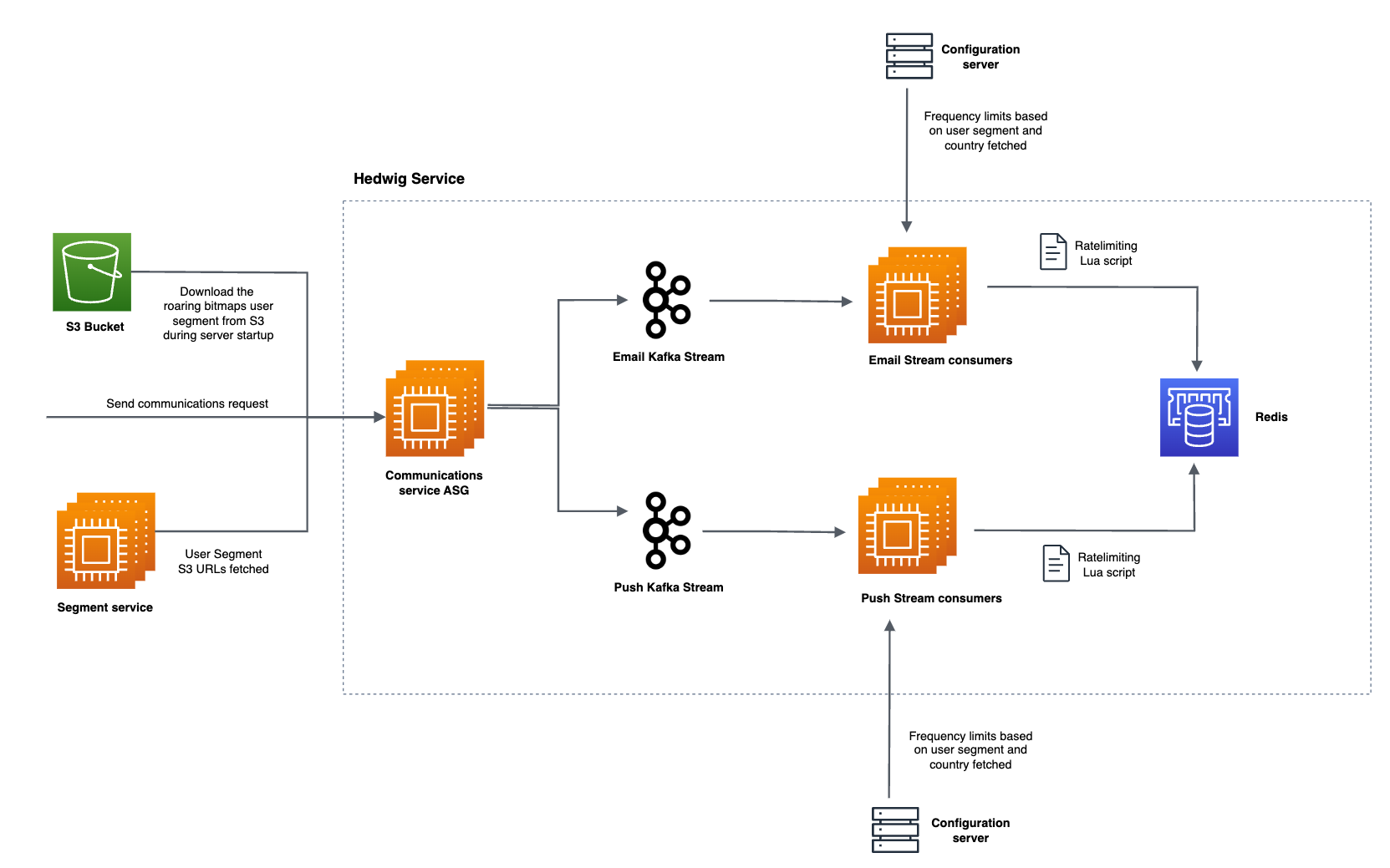

Trident relies on Hedwig, another in-house service, to deliver the messages to users. Hedwig does the heavy lifting of delivering large amounts of emails and push notifications to users while maintaining a high query per second (QPS) rate and minimal delay. The following high-level architectural illustration demonstrates the interaction between Trident and Hedwig.

The aim is to regulate the number of marketing comms sent to users daily and weekly, tailored based on their interaction patterns with the Grab superapp.

Solution

Based on their interaction patterns with our superapp, we have clustered users into a few segments.

For example:

New: Users recently signed up to the Grab app but haven’t taken any rides yet.

Active: Users who took rides in the past month.

With these metrics, we came up with optimal daily and weekly frequency limit values for each clustered user segment. The solution discussed in this article ensures that the comms sent to a user do not exceed the daily and weekly thresholds for the segment. This is also called frequency capping.

However, frequency capping can be split into two sub-problems:

Efficient storage of clustered user data

With a huge customer base of over 270 million users, storing the user segment membership information has to be cost-efficient and memory-sleek. Querying the segment to which a user belongs should also have minimal latency.

Persistent tracking of comms sent per user

To stay within the daily and weekly thresholds, we need to actively track the number of comms sent to each user, which can be referred to make rate limiting decisions. The rate limiting logic should also have minimal latency, be cost efficient, and not take up too much memory storage.

Optimising storage of user segment data

The problem here is figuring out which segment a particular user belongs to and ensuring that the user doesn’t appear in more than one segment. There are two options that suit our needs and we’ll explain more about each option, as well as what was the best option for us.

Bloom filter

A Bloom filter is a space-efficient probabilistic data structure that addresses this problem well. Simply put, Bloom filters internally use arrays to track memberships of the elements.

For our scenario, each user segment would need its own bloom filter. We used this bloom filter calculator to estimate the memory required for each bloom filter. We found that we needed approximately 1 GB of memory and 23 hash functions to accurately represent the membership information of 270 million users in an array. Additionally, this method guarantees a false positive rate of 1.0E-7, which means 1 in 1 million elements may get wrong membership results because of hash collision.

With Grab’s existing segments, this approach needs 4GB of memory, which may increase as we increase the number of segments in the future. Moreover, the potential hash collision needs to be handled by increasing the memory size with even more hash functions. Another thing to note is that Bloom filters do not support deletion so every time a change needs to be done, you need to create a new version of the Bloom filter. Although Bloom filters have many advantages, these shortcomings led us to explore another approach.

Roaring bitmaps

Roaring bitmaps are sets of unsigned integers consisting of containers of disjoint subsets, which can store large amounts of data in a compressed form. Essentially, roaring bitmaps could reduce memory storage significantly and overcome the hash collision problem. To understand the intuition behind this, first, we need to know how bitmaps work and the possible drawbacks behind it.

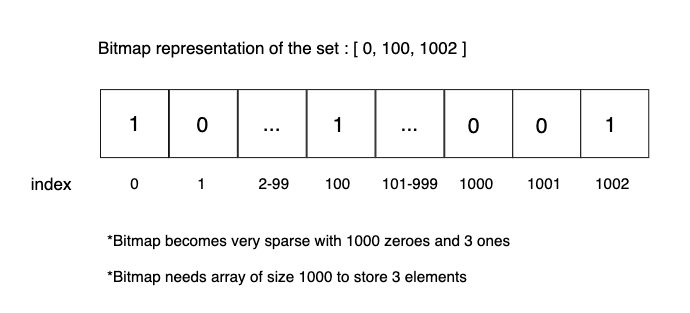

To represent a list of numbers as a bitmap, we first need to create an array with a size equivalent to the largest element in the list. For every element in the list, we then mark the bit value as 1 in the corresponding index in the array. While bitmaps work very well for storing integers in closer intervals, they occupy more space and become sparse when storing integer ranges with uneven distribution, as shown in the image below.

To reduce memory footprint and improve the performance of bitmaps, there are compression techniques such as Run-Length Encoding (RLE), and Word Aligned Hybrid (WAH). However, this would require additional effort to implement, whereas using roaring bitmaps would solve these issues.

Roaring bitmaps’ hybrid data storage approach offers the following advantages:

- Faster set operations (union, intersection, differencing).

- Better compression ratio when handling mixed datasets (both dense and sparse data distribution).

- Ability to scale to large datasets without significant performance loss.

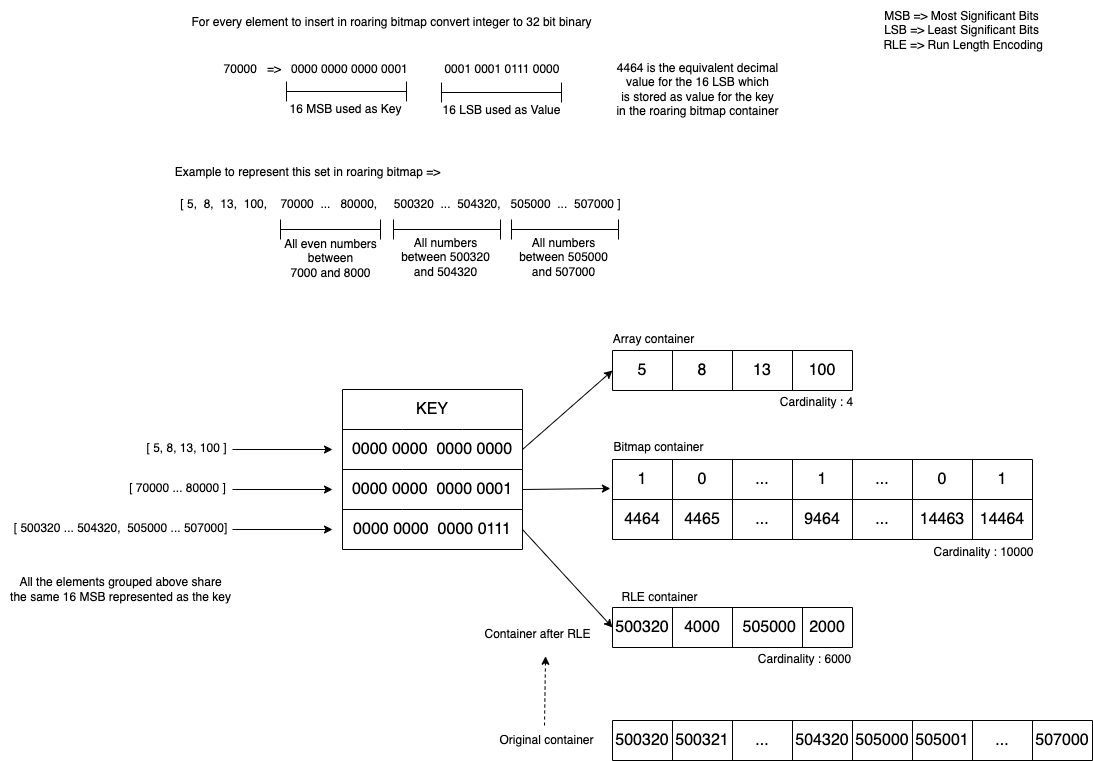

To summarise, roaring bitmaps can store positive integers from 0 to (2^32)-1. Each positive integer value is converted to a 32-bit binary, where the 16 Most Significant Bits (MSB) are used as the key and the remaining 16 Least Significant Bits (LSB) are represented as the value. The values are then stored in an array, a bitmap, or used to run containers with RLE encoding data structures.

If the number of integers mapped to the key is less than 4096, then all the integers are stored in an array in sorted order and converted into a bitmap container in the runtime as the size exceeds. Roaring bitmap analyses the distribution of set bits in the bitmap container i.e. if the continuous interval of set bits is more than a given threshold, the bitmap container can be more efficiently represented using the RLE container. Internally, the RLE container uses an array where the even indices store the beginning of the runs and the odd indices represent the length of the runs. This enables the roaring bitmap to dynamically switch between the containers to optimise storage and performance.

The following diagram shows how a set of elements with different distributions are stored in roaring bitmaps.

In Grab, we developed a microservice that abstracts roaring bitmaps implementations and provides an API to check set membership and enumeration of elements in the sets. Check out this blog to learn more about it.

Distributed rate limiting

The second part of the problem involves rate limiting the number of communication messages sent to users on a daily or weekly basis and each segment has specific daily and weekly limits. By utilising roaring bitmaps, we can determine the segment to which a user belongs. After identifying the appropriate segment, we will apply the personalised limits to the user using a distributed rate limiter, which will be discussed in further detail in the following sections.

Choosing the right datastore

Based on our use case, Amazon ElasticCache for Redis and DynamoDB were two viable options for storing the sent communication messages count per user. However, we decided to choose Redis due to a number of factors:

- Higher throughput at lower latency – Redis shards data across nodes in the cluster.

- Cost-effective – Usage of Lua script reduces unnecessary data transfer overheads.

- Better at handling spiky rate limiting workloads at scale.

Distributed rate limiter

To appropriately limit the comms our users receive, we needed a rate limiting algorithm, which could execute directly in the datastore cluster, then return the results in the application logic for further processing. The two rate limiting algorithms we considered were the sliding window rate limiter and sliding log rate limiter.

The sliding window rate limiter algorithm divides time into a fixed-size window (we defined this as 1 minute) and counts the number of requests within each window. On the other hand, the sliding log maintains a log of each request timestamp and counts the number of requests between two timestamp ranges, providing a more fine-grained method of rate limiting. Although sliding log consumes more memory to store the log of request timestamp, we opted for the sliding log approach as the accuracy of the rate limiting was more important than memory consumption.

The sliding log rate limiter utilises a Redis sorted set data structure to efficiently track and organise request logs. Each timestamp in milliseconds is stored as a unique member in the set. The score assigned to each member represents the corresponding timestamp, allowing for easy sorting in ascending order. This design choice optimises the speed of search operations when querying for the total request count within specific time ranges.

Sliding Log Rate limiter Algorithm:

Input:

# user specific redis key where the request timestamp logs are stored as sorted set

keys => user_redis_key

# limit_value is the limit that needs to be applied for the user

# start_time_in_millis is the starting point of the time window

# end_time_in_millis is the ending point of the time window

# current_time_in_millis is the current time the request is sent

# eviction_time_in_millis, members in the set whose value is less than this will be evicted from the set

args => limit_value, start_time_in_millis, end_time_in_millis, current_time_in_millis, eviction_time_in_millis

Output:

# 0 means not_allowed and 1 means allowed

response => 0 / 1

Logic:

# zcount fetches the count of the request timestamp logs falling between the start and the end timestamp

request_count = zcount user_redis_key start_time_in_millis end_time_in_millis

response = 0

# if the count of request logs is less than allowed limits then record the usage by adding current timestamp in sorted set

if request_count < limit_value then

zadd user_redis_key current_time_in_millis current_time_in_millis

response = 1

# zremrangebyscore removes the members in the sorted set whose score is less than eviction_time_in_millis

zremrangebyscore user_redis_key -inf eviction_time_in_millis

return response

This algorithm takes O(log n) time complexity, where n is the number of request logs stored in the sorted set. It is not possible to evict entries in the sorted set like how we have time-to-live (TTL) for Redis keys. To prevent the size of the sorted set from increasing over time, we have a fixed variable eviction_time_in_millis that is passed to the script. The zremrangebyscore command then deletes members from the sorted set whose score is less than eviction_time_in_millis in O(log n) time complexity.

Lua script optimisations

In Redis Cluster mode, all Redis keys accessed by a Lua script must be present on the same node, and they should be passed as part of the KEYS input array of the script. If the script attempts to access keys located on different nodes within the cluster, a CROSSSLOT error will be thrown. Redis keys, or userIDs, are distributed across multiple nodes in the cluster so it is not feasible to send a batch of userIDs within the same Lua script for rate limiting, as this might result in a CROSSSLOT error.

Invoking a separate Lua script call for each user is a possible approach, but it incurs a significant number of network calls, which can be optimised further with the following approach:

- Upload the Lua script into the Redis server during the server startup with the

SCRIPT LOADcommand and we get the SHA1 hash of the script if the upload is successful. - The SHA1 hash can then be used to invoke the Lua script with the

EVALSHAcommand passing the keys and arguments as script input. - Redis pipelining takes in multiple

EVALSHAcommands that call the Lua script and each invocation corresponds to a userID for getting the rate limiting result. - Redis pipelining groups the

EVALSHARedis commands with Redis keys located on the same nodes internally. It then sends the grouped commands in a single network call to the relevant nodes within the Redis cluster and provides the rate limiting outcome to the client.

Since Redis operates on a single thread, any long-running Lua script can cause other Redis commands to be blocked until the script completes execution. Thus, it’s optimal for the Lua script to execute in under 5 milliseconds. Additionally, the current time is passed as an argument to the script to account for potential variations in time when the script is executed on a node’s replica, which could be caused by clock drift.

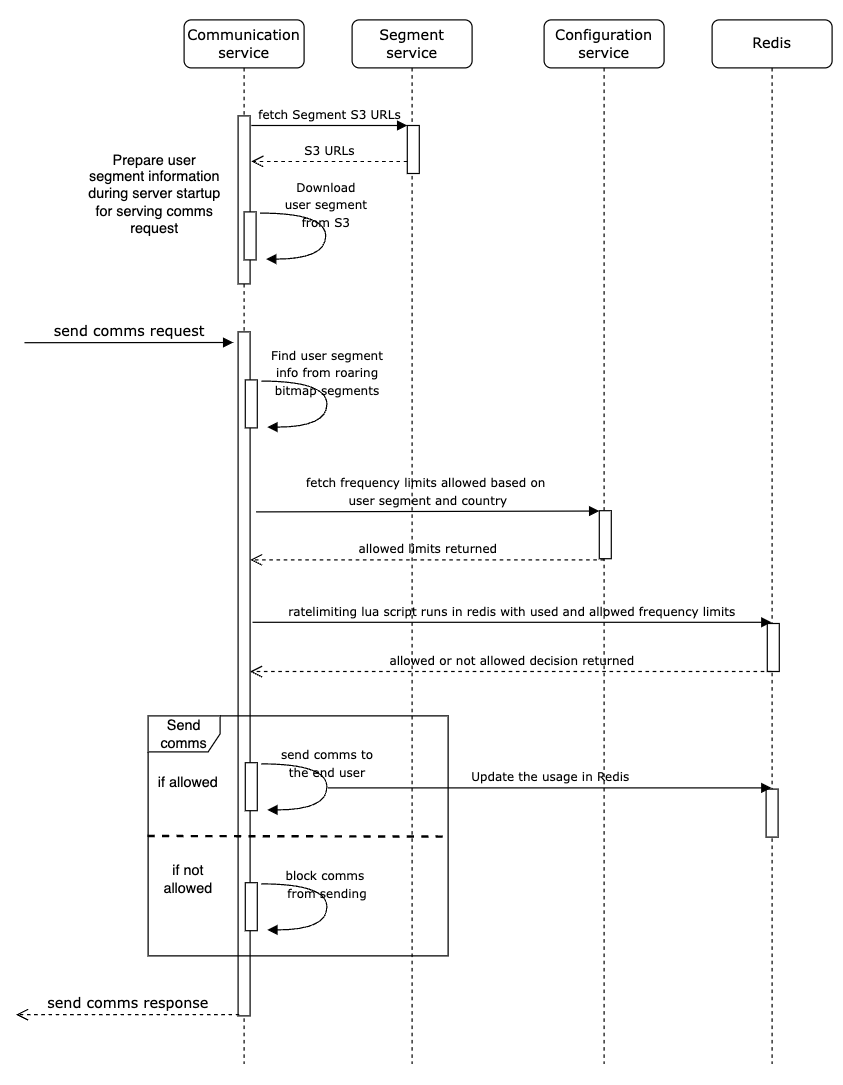

By bringing together roaring bitmaps and the distributed rate limiter, this is what our final solution looks like:

The roaring bitmaps structure is serialised and stored in an AWS S3 bucket, which is then downloaded in the instance during server startup. After which, triggering a user segment membership check can simply be done with a local method call. The configuration service manages the mapping information between the segment and allowed rate limiting values.

Whenever a marketing message needs to be sent to a user, we first find the segment to which the user belongs, retrieve the defined rate limiting values from the configuration service, then execute the Lua script to get the rate limiting decision. If there is enough quota available for the user, we send the comms.

The architecture of the messaging service looks something like this:

Impact

In addition to decreasing the unsubscription rate, there was a significant enhancement in the latency of sending communications. Eliminating redundant communications also alleviated the system load, resulting in a reduction of the delay between the scheduled time and the actual send time of comms.

Conclusion

Applying rate limiters to safeguard our services is not only a standard practice but also a necessary process. Many times, this can be achieved by configuring the rate limiters at the instance level. The need for rate limiters for business logic may not be as common, but when you need it, the solution must be lightning-fast, and capable of seamlessly operating within a distributed environment.

Join us

Grab is the leading superapp platform in Southeast Asia, providing everyday services that matter to consumers. More than just a ride-hailing and food delivery app, Grab offers a wide range of on-demand services in the region, including mobility, food, package and grocery delivery services, mobile payments, and financial services across 428 cities in eight countries.

Powered by technology and driven by heart, our mission is to drive Southeast Asia forward by creating economic empowerment for everyone. If this mission speaks to you, join our team today!