Engineering

·

Data Science

Engineering

·

Data Science

Kafka on Kubernetes: Reloaded for fault tolerance

Introduction

Coban - Grab’s real-time data streaming platform - has been operating Kafka on Kubernetes with Strimzi in production for about two years. In a previous article (Zero trust with Kafka), we explained how we leveraged Strimzi to enhance the security of our data streaming offering.

In this article, we are going to describe how we improved the fault tolerance of our initial design, to the point where we no longer need to intervene if a Kafka broker is unexpectedly terminated.

Problem statement

We operate Kafka in the AWS Cloud. For the Kafka on Kubernetes design described in this article, we rely on Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS), the managed Kubernetes offering by AWS, with the worker nodes deployed as self-managed nodes on Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2).

To make our operations easier and limit the blast radius of any incidents, we deploy exactly one Kafka cluster for each EKS cluster. We also give a full worker node to each Kafka broker. In terms of storage, we initially relied on EC2 instances with non-volatile memory express (NVMe) instance store volumes for maximal I/O performance. Also, each Kafka cluster is accessible beyond its own Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) via a VPC Endpoint Service.

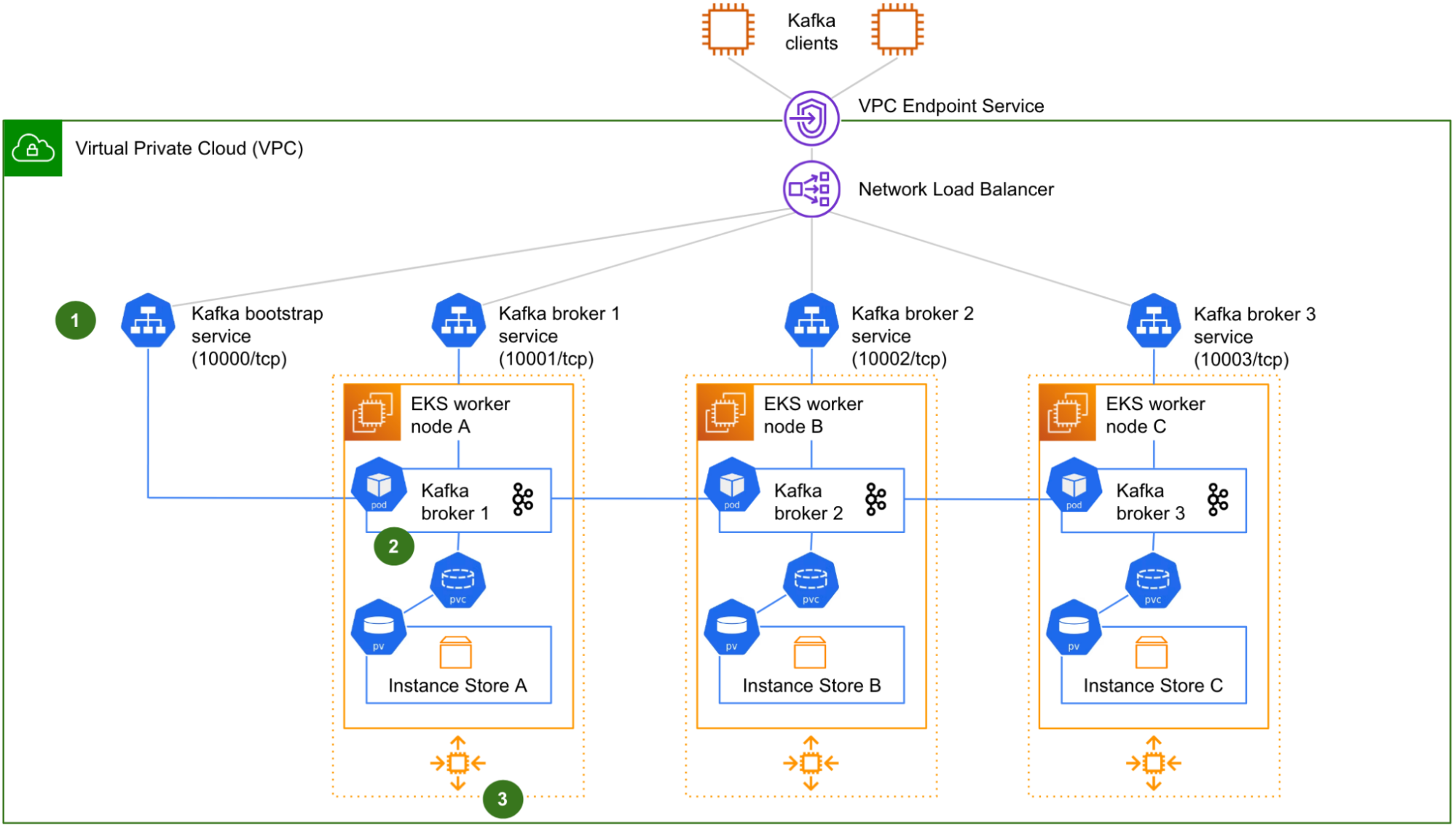

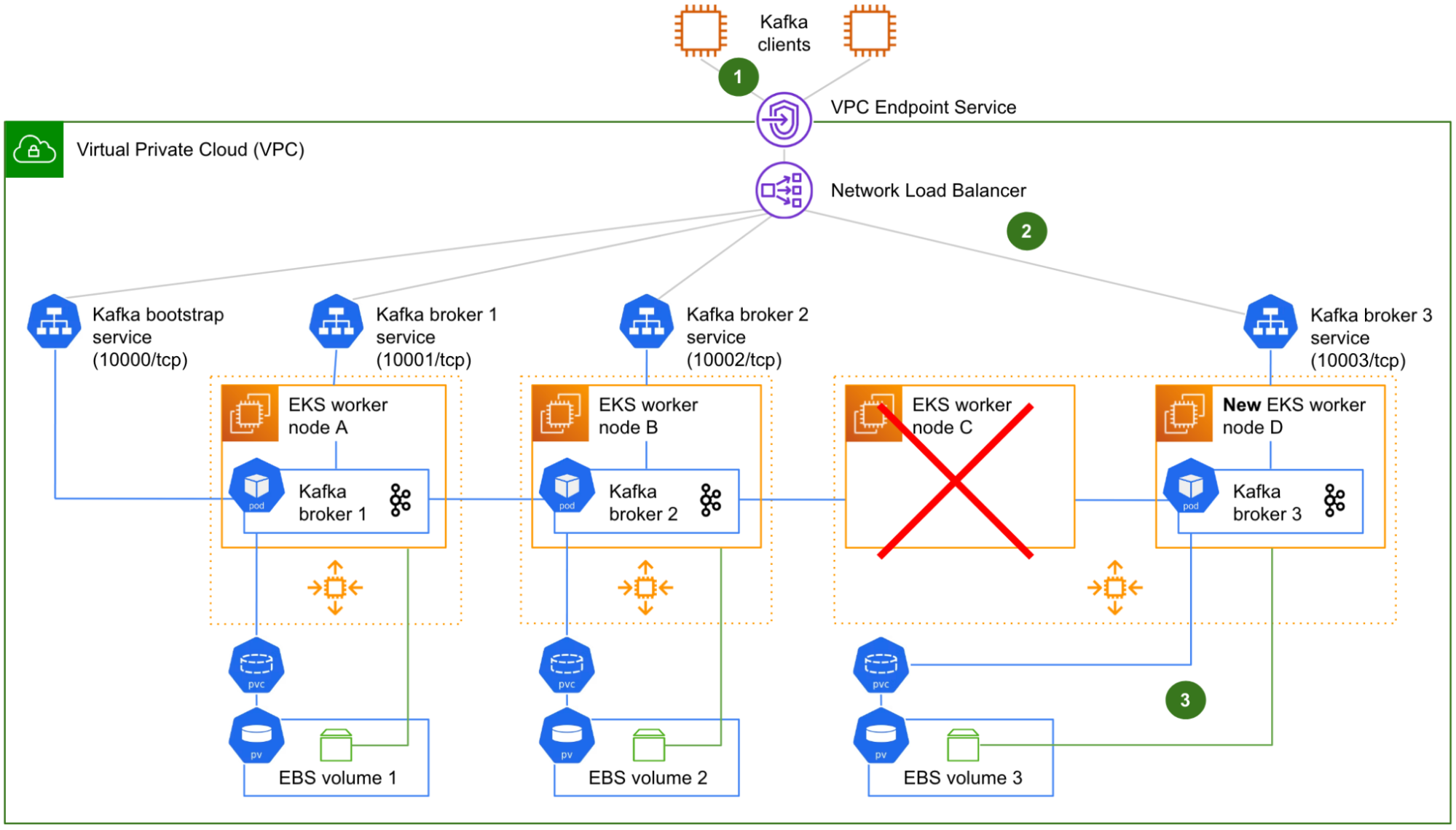

Fig. 1 shows a logical view of our initial design of a 3-node Kafka on Kubernetes cluster, as typically run by Coban. The Zookeeper and Cruise-Control components are not shown for clarity.

There are four Kubernetes services (1): one for the initial connection - referred to as “bootstrap” - that redirects incoming traffic to any Kafka pods, plus one for each Kafka pod, for the clients to target each Kafka broker individually (a requirement to produce or consume from/to a partition that resides on any particular Kafka broker). Four different listeners on the Network Load Balancer (NLB) listening on four different TCP ports, enable the Kafka clients to target either the bootstrap service or any particular Kafka broker they need to reach. This is very similar to what we previously described in Exposing a Kafka Cluster via a VPC Endpoint Service.

Each worker node hosts a single Kafka pod (2). The NVMe instance store volume is used to create a Kubernetes Persistent Volume (PV), attached to a pod via a Kubernetes Persistent Volume Claim (PVC).

Lastly, the worker nodes belong to Auto-Scaling Groups (ASG) (3), one by Availability Zone (AZ). Strimzi adds in node affinity to make sure that the brokers are evenly distributed across AZs. In this initial design, ASGs are not for auto-scaling though, because we want to keep the size of the cluster under control. We only use ASGs - with a fixed size - to facilitate manual scaling operation and to automatically replace the terminated worker nodes.

With this initial design, let us see what happens in case of such a worker node termination.

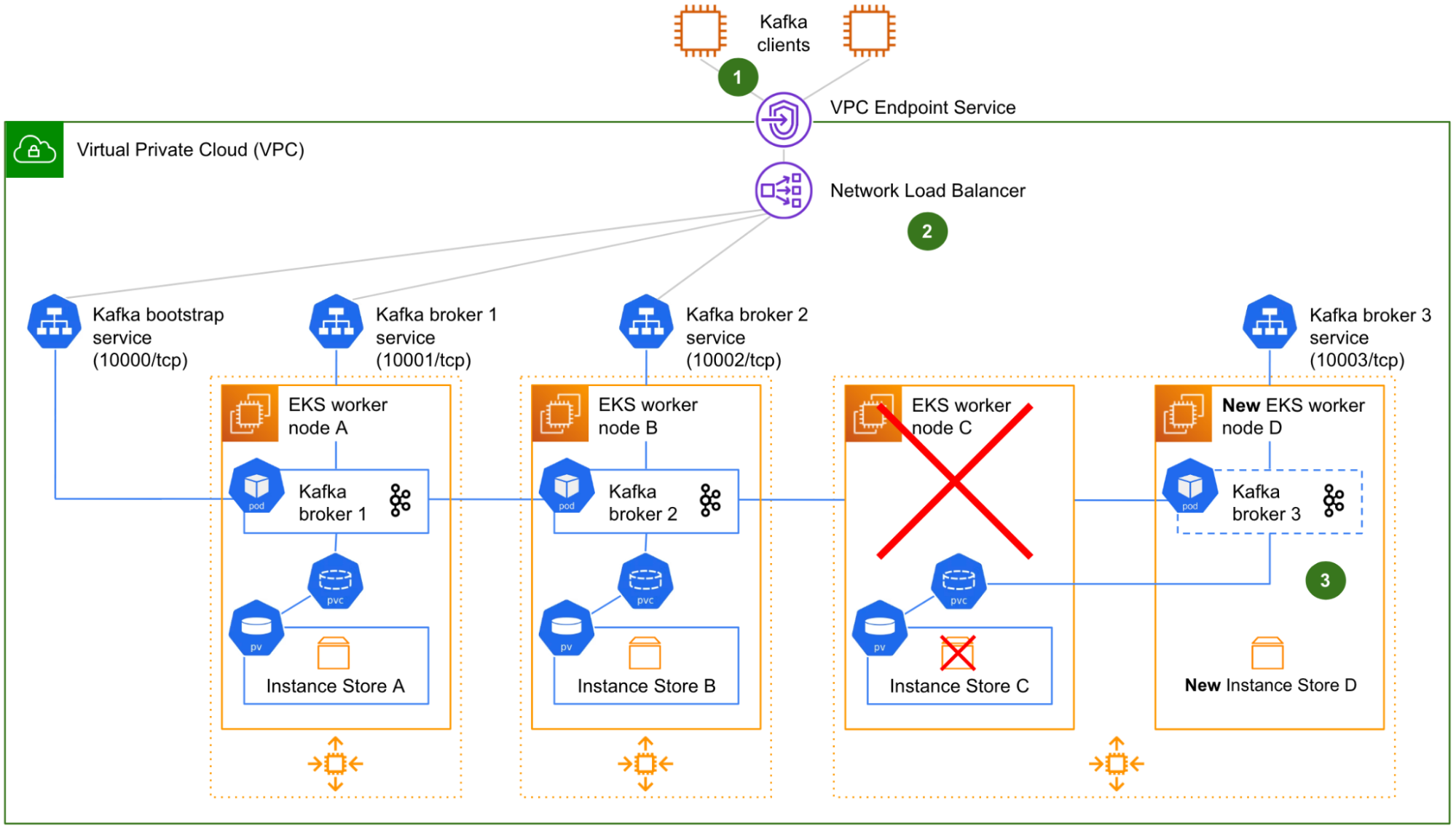

Fig. 2 shows the worker node C being terminated along with its NVMe instance store volume C, and replaced (by the ASG) by a new worker node D and its new, empty NVMe instance store volume D. On start-up, the worker node D automatically joins the Kubernetes cluster. The Kafka broker 3 pod that was running on the faulty worker node C is scheduled to restart on the new worker node D.

Although the NVMe instance store volume C is terminated along with the worker node C, there is no data loss because all of our Kafka topics are configured with a minimum of three replicas. The data is poised to be copied over from the surviving Kafka brokers 1 and 2 back to Kafka broker 3, as soon as Kafka broker 3 is effectively restarted on the worker node D.

However, there are three fundamental issues with this initial design:

- The Kafka clients that were in the middle of producing or consuming to/from the partition leaders of Kafka broker 3 are suddenly facing connection errors, because the broker was not gracefully demoted beforehand.

- The target groups of the NLB for both the bootstrap connection and Kafka broker 3 still point to the worker node C. Therefore, the network communication from the NLB to Kafka broker 3 is broken. A manual reconfiguration of the target groups is required.

- The PVC associating the Kafka broker 3 pod with its instance store PV is unable to automatically switch to the new NVMe instance store volume of the worker node D. Indeed, static provisioning is an intrinsic characteristic of Kubernetes local volumes. The PVC is still in Bound state, so Kubernetes does not take any action. However, the actual storage beneath the PV does not exist anymore. Without any storage, the Kafka broker 3 pod is unable to start.

At this stage, the Kafka cluster is running in a degraded state with only two out of three brokers, until a Coban engineer intervenes to reconfigure the target groups of the NLB and delete the zombie PVC (this, in turn, triggers its re-creation by Strimzi, this time using the new instance store PV).

In the next section, we will see how we have managed to address the three issues mentioned above to make this design fault-tolerant.

Solution

Graceful Kafka shutdown

To minimise the disruption for the Kafka clients, we leveraged the AWS Node Termination Handler (NTH). This component provided by AWS for Kubernetes environments is able to cordon and drain a worker node that is going to be terminated. This draining, in turn, triggers a graceful shutdown of the Kafka process by sending a polite SIGTERM signal to all pods running on the worker node that is being drained (instead of the brutal SIGKILL of a normal termination).

The termination events of interest that are captured by the NTH are:

- Scale-in operations by an ASG.

- Manual termination of an instance.

- AWS maintenance events, typically EC2 instances scheduled for upcoming retirement.

This suffices for most of the disruptions our clusters can face in normal times and our common maintenance operations, such as terminating a worker node to refresh it. Only sudden hardware failures (AWS issue events) would fall through the cracks and still trigger errors on the Kafka client side.

The NTH comes in two modes: Instance Metadata Service (IMDS) and Queue Processor. We chose to go with the latter as it is able to capture a broader range of events, widening the fault tolerance capability.

Scale-in operations by an ASG

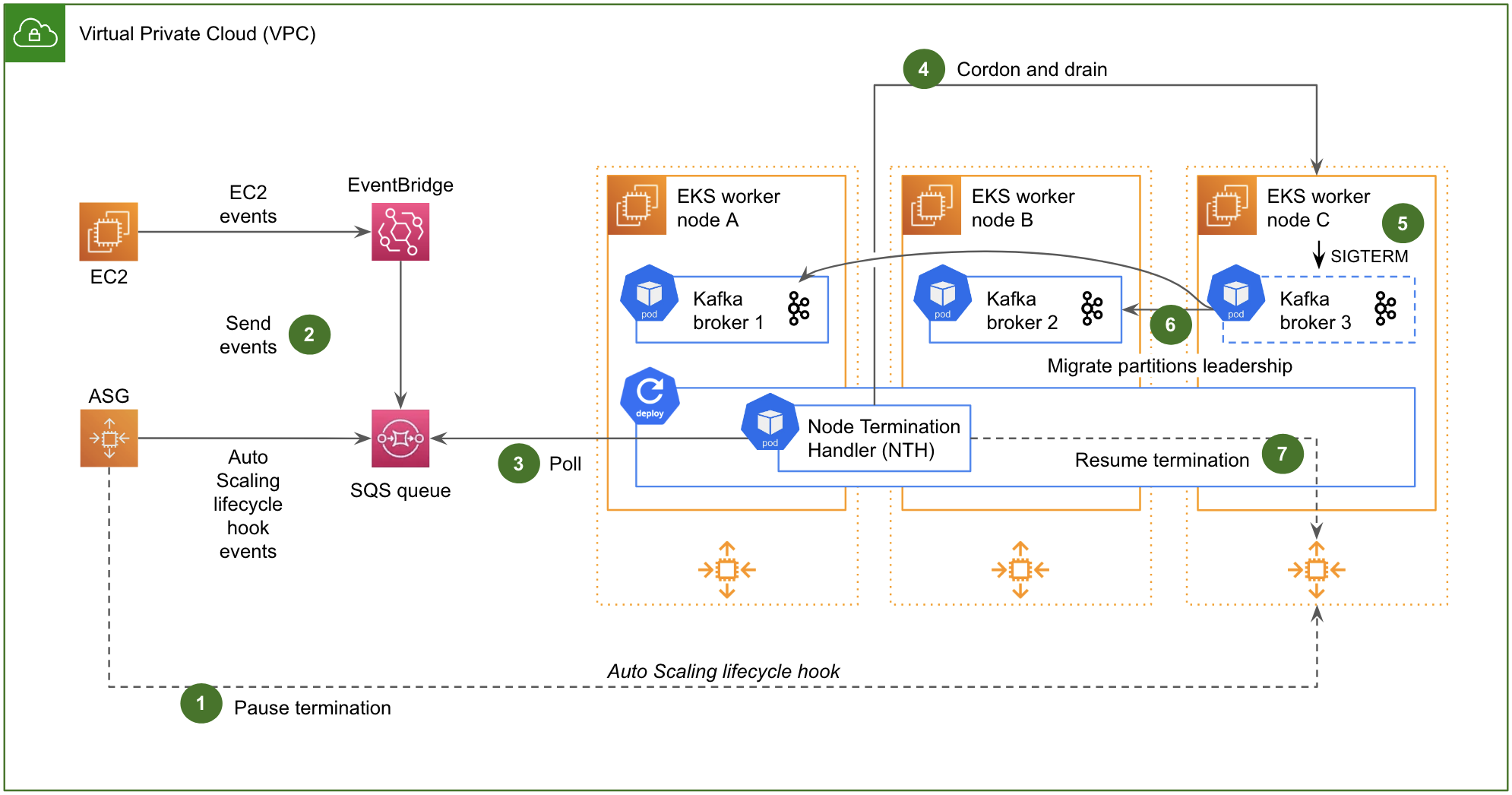

Fig. 3 shows the NTH with the Queue Processor in action, and how it reacts to a scale-in operation (typically triggered manually, during a maintenance operation):

- As soon as the scale-in operation is triggered, an Auto Scaling lifecycle hook is invoked to pause the termination of the instance.

- Simultaneously, an Auto Scaling lifecycle hook event is issued to an Amazon Simple Queue Service (SQS) queue. In Fig. 3, we have also materialised EC2 events (e.g. manual termination of an instance, AWS maintenance events, etc.) that transit via Amazon EventBridge to eventually end up in the same SQS queue. We will discuss EC2 events in the next two sections.

- The NTH, a pod running in the Kubernetes cluster itself, constantly polls that SQS queue.

- When a scale-in event pertaining to a worker node of the Kubernetes cluster is read from the SQS queue, the NTH sends to the Kubernetes API the instruction to cordon and drain the impacted worker node.

- On draining, Kubernetes sends a SIGTERM signal to the Kafka pod residing on the worker node.

- Upon receiving the SIGTERM signal, the Kafka pod gracefully migrates the leadership of its leader partitions to other brokers of the cluster before shutting down, in a transparent manner for the clients. This behaviour is ensured by the

controlled.shutdown.enableparameter of Kafka, which is enabled by default. - Once the impacted worker node has been drained, the NTH eventually resumes the termination of the instance.

Strimzi also comes with a terminationGracePeriodSeconds parameter, which we have set to 180 seconds to give the Kafka pods enough time to migrate all of their partition leaders gracefully on termination. We have verified that this is enough to migrate all partition leaders on our Kafka clusters (about 60 seconds for 600 partition leaders).

Manual termination of an instance

The Auto Scaling lifecycle hook that pauses the termination of an instance (Fig. 3, step 1) as well as the corresponding resuming by the NTH (Fig. 3, step 7) are invoked only for ASG scaling events.

In case of a manual termination of an EC2 instance, the termination is captured as an EC2 event that also reaches the NTH. Upon receiving that event, the NTH cordons and drains the impacted worker node. However, the instance is immediately terminated, most likely before the leadership of all of its Kafka partition leaders has had the time to get migrated to other brokers.

To work around this and let a manual termination of an EC2 instance also benefit from the ASG lifecycle hook, the instance must be terminated using the terminate-instance-in-auto-scaling-group AWS CLI command.

AWS maintenance events

For AWS maintenance events such as instances scheduled for upcoming retirement, the NTH acts immediately when the event is first received (typically adequately in advance). It cordons and drains the soon-to-be-retired worker node, which in turn triggers the SIGTERM signal and the graceful termination of Kafka as described above. At this stage, the impacted instance is not terminated, so the Kafka partition leaders have plenty of time to complete their migration to other brokers.

However, the evicted Kafka pod has nowhere to go. There is a need for spinning up a new worker node for it to be able to eventually restart somewhere.

To make this happen seamlessly, we doubled the maximum size of each of our ASGs and installed the Kubernetes Cluster Autoscaler. With that, when such a maintenance event is received:

- The worker node scheduled for retirement is cordoned and drained by the NTH. The state of the impacted Kafka pod becomes Pending.

- The Kubernetes Cluster Autoscaler comes into play and triggers the corresponding ASG to spin up a new EC2 instance that joins the Kubernetes cluster as a new worker node.

- The impacted Kafka pod restarts on the new worker node.

- The Kubernetes Cluster Autoscaler detects that the previous worker node is now under-utilised and terminates it.

In this scenario, the impacted Kafka pod only remains in Pending state for about four minutes in total.

In case of multiple simultaneous AWS maintenance events, the Kubernetes scheduler would honour our PodDisruptionBudget and not evict more than one Kafka pod at a time.

Dynamic NLB configuration

To automatically map the NLB’s target groups with a newly spun up EC2 instance, we leveraged the AWS Load Balancer Controller (LBC).

Let us see how it works.

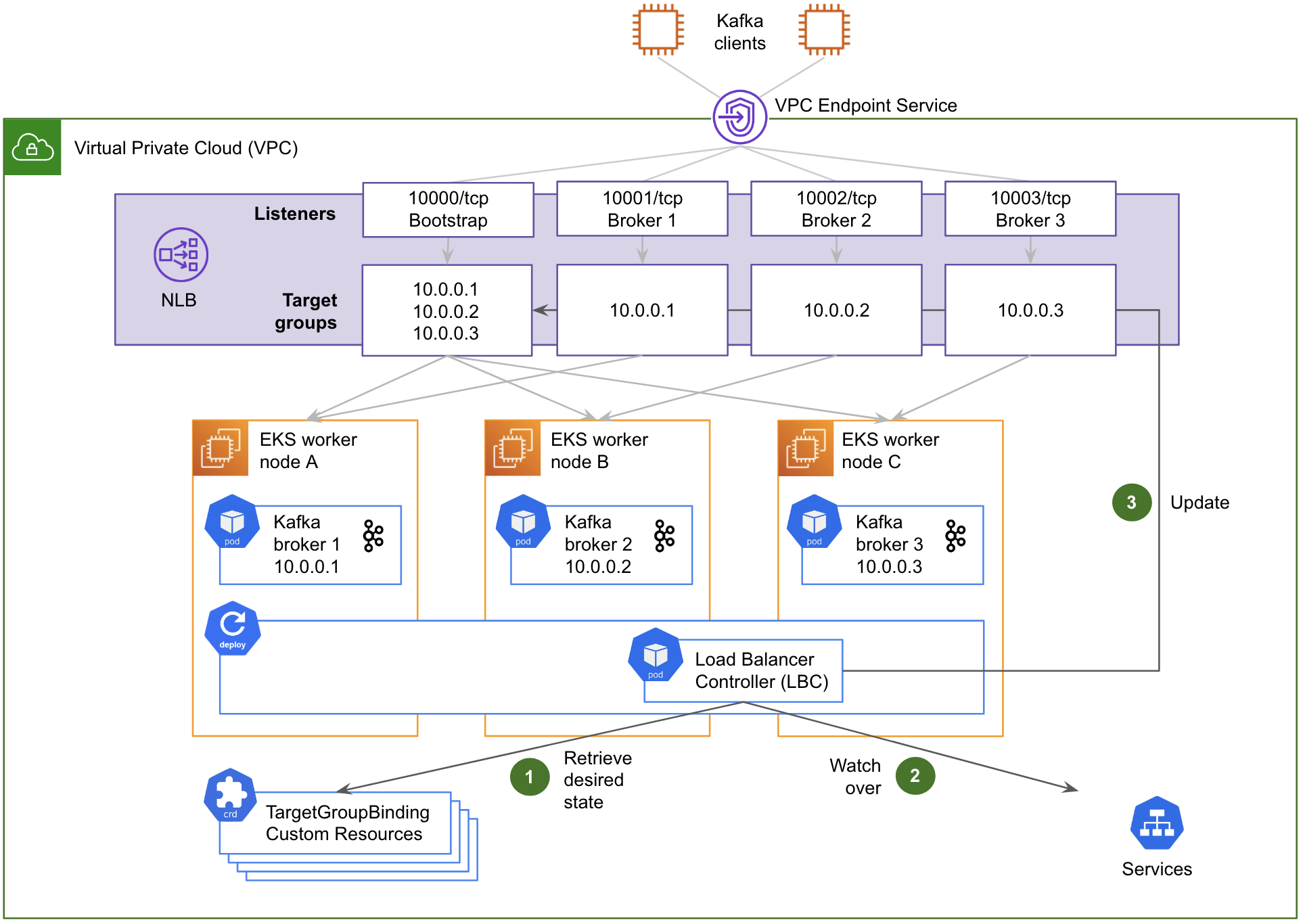

Fig. 4 shows how the LBC automates the reconfiguration of the NLB’s target groups:

- It first retrieves the desired state described in Kubernetes custom resources (CR) of type TargetGroupBinding. There is one such resource per target group to maintain. Each TargetGroupBinding CR associates its respective target group with a Kubernetes service.

- The LBC then watches over the changes of the Kubernetes services that are referenced in the TargetGroupBinding CRs’ definition, specifically the private IP addresses exposed by their respective Endpoints resources.

- When a change is detected, it dynamically updates the corresponding NLB’s target groups with those IP addresses as well as the TCP port of the target containers (

containerPort).

This automated design sets up the NLB’s target groups with IP addresses (targetType: ip) instead of EC2 instance IDs (targetType: instance). Although the LBC can handle both target types, the IP address approach is actually more straightforward in our case, since each pod has a routable private IP address in the AWS subnet, thanks to the AWS Container Networking Interface (CNI) plug-in.

This dynamic NLB configuration design comes with a challenge. Whenever we need to update the Strimzi CR, the rollout of the change to each Kafka pod in a rolling update fashion is happening too fast for the NLB. This is because the NLB inherently takes some time to mark each target as healthy before enabling it. The Kafka brokers that have just been rolled out start advertising their broker-specific endpoints to the Kafka clients via the bootstrap service, but those

endpoints are actually not immediately available because the NLB is still checking their health. To mitigate this, we have reduced the HealthCheckIntervalSeconds and HealthyThresholdCount parameters of each target group to their minimum values of 5 and 2 respectively. This reduces the maximum delay for the NLB to detect that a target has become healthy to 10 seconds. In addition, we have configured the LBC with a Pod Readiness Gate. This feature makes the Strimzi rolling deployment wait for the health check of the NLB to pass, before marking the current pod as Ready and proceeding with the next pod.

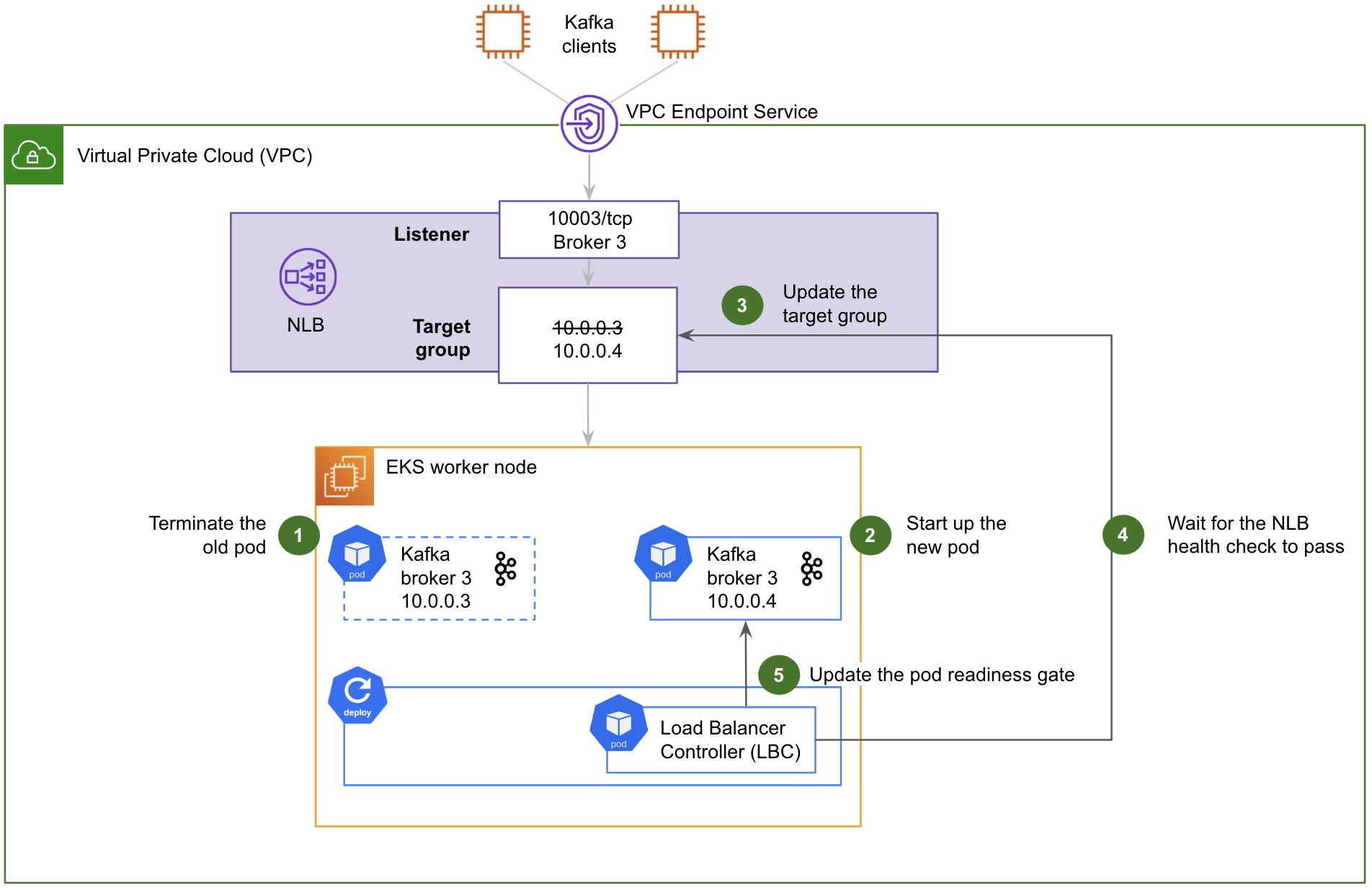

Fig. 5 shows how the Pod Readiness Gate works during a Strimzi rolling deployment:

- The old Kafka pod is terminated.

- The new Kafka pod starts up and joins the Kafka cluster. Its individual endpoint for direct access via the NLB is immediately advertised by the Kafka cluster. However, at this stage, it is not reachable, as the target group of the NLB still points to the IP address of the old Kafka pod.

- The LBC updates the target group of the NLB with the IP address of the new Kafka pod, but the NLB health check has not yet passed, so the traffic is not forwarded to the new Kafka pod just yet.

- The LBC then waits for the NLB health check to pass, which takes 10 seconds. Once the NLB health check has passed, the NLB resumes forwarding the traffic to the Kafka pod.

- Finally, the LBC updates the pod readiness gate of the new Kafka pod. This informs Strimzi that it can proceed with the next pod of the rolling deployment.

Data persistence with EBS

To address the challenge of the residual PV and PVC of the old worker node preventing Kubernetes from mounting the local storage of the new worker node after a node rotation, we adopted Elastic Block Store (EBS) volumes instead of NVMe instance store volumes. Contrary to the latter, EBS volumes can conveniently be attached and detached. The trade-off is that their performance is significantly lower.

However, relying on EBS comes with additional benefits:

- The cost per GB is lower, compared to NVMe instance store volumes.

- Using EBS decouples the size of an instance in terms of CPU and memory from its storage capacity, leading to further cost savings by independently right-sizing the instance type and its storage. Such a separation of concerns also opens the door to new use cases requiring disproportionate amounts of storage.

- After a worker node rotation, the time needed for the new node to get back in sync is faster, as it only needs to catch up the data that was produced during the downtime. This leads to shorter maintenance operations and higher iteration speed. Incidentally, the associated inter-AZ traffic cost is also lower, since there is less data to transfer among brokers during this time.

- Increasing the storage capacity is an online operation.

- Data backup is supported by taking snapshots of EBS volumes.

We have verified with our historical monitoring data that the performance of EBS General Purpose 3 (gp3) volumes is significantly above our maximum historical values for both throughput and I/O per second (IOPS), and we have successfully benchmarked a test EBS-based Kafka cluster. We have also set up new monitors to be alerted in case we need to provision either additional throughput or IOPS, beyond the baseline of EBS gp3 volumes.

With that, we updated our instance types from storage optimised instances to either general purpose or memory optimised instances. We added the Amazon EBS Container Storage Interface (CSI) driver to the Kubernetes cluster and created a new Kubernetes storage class to let the cluster dynamically provision EBS gp3 volumes.

We configured Strimzi to use that storage class to create any new PVCs. This makes Strimzi able to automatically create the EBS volumes it needs, typically when the cluster is first set up, but also to attach/detach the volumes to/from the EC2 instances whenever a Kafka pod is relocated to a different worker node.

Note that the EBS volumes are not part of any ASG Launch Template, nor do they scale automatically with the ASGs.

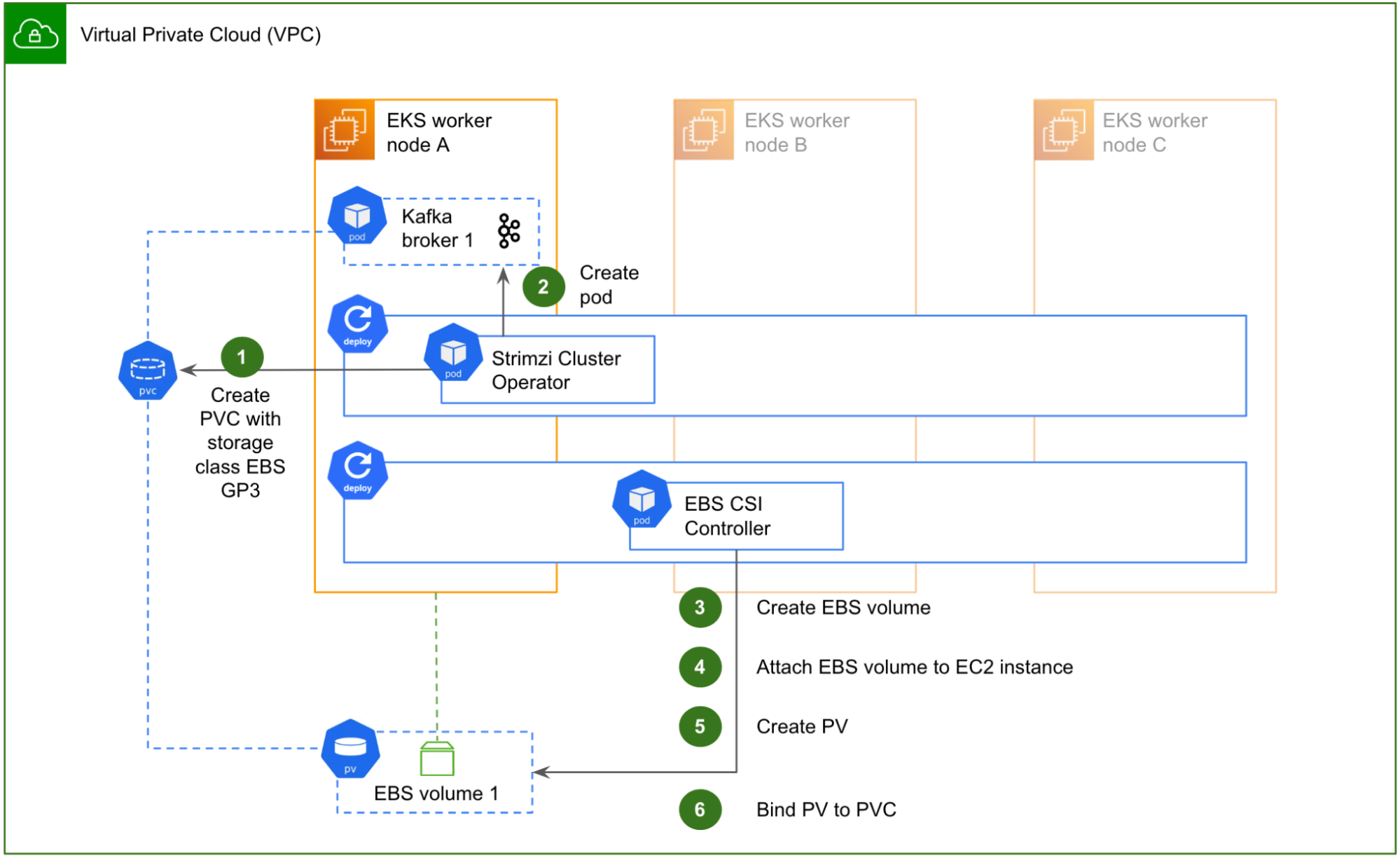

Fig. 6 illustrates how this works when Strimzi sets up a new Kafka broker, for example the first broker of the cluster in the initial setup:

- The Strimzi Cluster Operator first creates a new PVC, specifying a volume size and EBS gp3 as its storage class. The storage class is configured with the EBS CSI Driver as the volume provisioner, so that volumes are dynamically provisioned [1]. However, because it is also set up with

volumeBindingMode: WaitForFirstConsumer, the volume is not yet provisioned until a pod actually claims the PVC. - The Strimzi Cluster Operator then creates the Kafka pod, with a reference to the newly created PVC. The pod is scheduled to start, which in turn claims the PVC.

- This triggers the EBS CSI Controller. As the volume provisioner, it dynamically creates a new EBS volume in the AWS VPC, in the AZ of the worker node where the pod has been scheduled to start.

- It then attaches the newly created EBS volume to the corresponding EC2 instance.

- After that, it creates a Kubernetes PV with nodeAffinity and claimRef specifications, making sure that the PV is reserved for the Kafka broker 1 pod.

- Lastly, it updates the PVC with the reference of the newly created PV. The PVC is now in Bound state and the Kafka pod can start.

One important point to take note of is that EBS volumes can only be attached to EC2 instances residing in their own AZ. Therefore, when rotating a worker node, the EBS volume can only be re-attached to the new instance if both old and new instances reside in the same AZ. A simple way to guarantee this is to set up one ASG per AZ, instead of a single ASG spanning across 3 AZs.

Also, when such a rotation occurs, the new broker only needs to synchronise the recent data produced during the brief downtime, which is typically an order of magnitude faster than replicating the entire volume (depending on the overall retention period of the hosted Kafka topics).

| Initial design (NVMe instance store volumes) | New design (EBS volumes) | |

|---|---|---|

| Data to synchronise | All of the data | Recent data produced during the brief downtime |

| Function of (primarily) | Retention period | Downtime |

| Typical duration | Hours | Minutes |

Outcome

With all that, let us revisit the initial scenario, where a malfunctioning worker node is being replaced by a fresh new node.

Fig. 7 shows the worker node C being terminated and replaced (by the ASG) by a new worker node D, similar to what we have described in the initial problem statement. The worker node D automatically joins the Kubernetes cluster on start-up.

However, this time, a seamless failover takes place:

- The Kafka clients that were in the middle of producing or consuming to/from the partition leaders of Kafka broker 3 are gracefully redirected to Kafka brokers 1 and 2, where Kafka has migrated the leadership of its leader partitions.

- The target groups of the NLB for both the bootstrap connection and Kafka broker 3 are automatically updated by the LBC. The connectivity between the NLB and Kafka broker 3 is immediately restored.

- Triggered by the creation of the Kafka broker 3 pod, the Amazon EBS CSI driver running on the worker node D re-attaches the EBS volume 3 that was previously attached to the worker node C, to the worker node D instead. This enables Kubernetes to automatically re-bind the corresponding PV and PVC to Kafka broker 3 pod. With its storage dependency resolved, Kafka broker 3 is able to start successfully and re-join the Kafka cluster. From there, it only needs to catch up with the new data that was produced during its short downtime, by replicating it from Kafka brokers 1 and 2.

With this fault-tolerant design, when an EC2 instance is being retired by AWS, no particular action is required from our end.

Similarly, our EKS version upgrades, as well as any operations that require rotating all worker nodes of the cluster in general, are:

- Simpler and less error-prone: We only need to rotate each instance in sequence, with no need for manually reconfiguring the target groups of the NLB and deleting the zombie PVCs anymore.

- Faster: The time between each instance rotation is limited to the short amount of time it takes for the restarted Kafka broker to catch up with the new data.

- More cost-efficient: There is less data to transfer across AZs (which is charged by AWS).

It is worth noting that we have chosen to omit Zookeeper and Cruise Control in this article, for the sake of clarity and simplicity. In reality, all pods in the Kubernetes cluster - including Zookeeper and Cruise Control - now benefit from the same graceful stop, triggered by the AWS termination events and the NTH. Similarly, the EBS CSI driver improves the fault tolerance of any pods that use EBS volumes for persistent storage, which includes the Zookeeper pods.

Challenges faced

One challenge that we are facing with this design lies in the EBS volumes’ management.

On the one hand, the size of EBS volumes cannot be increased consecutively before the end of a cooldown period (minimum of 6 hours and can exceed 24 hours in some cases [2]). Therefore, when we need to urgently extend some EBS volumes because the size of a Kafka topic is suddenly growing, we need to be relatively generous when sizing the new required capacity and add a comfortable security margin, to make sure that we are not running out of storage in the short run.

On the other hand, shrinking a Kubernetes PV is not a supported operation. This can affect the cost efficiency of our design if we overprovision the storage capacity by too much, or in case the workload of a particular cluster organically diminishes.

One way to mitigate this challenge is to tactically scale the cluster horizontally (ie. adding new brokers) when there is a need for more storage and the existing EBS volumes are stuck in a cooldown period, or when the new storage need is only temporary.

What’s next?

In the future, we can improve the NTH’s capability by utilising webhooks. Upon receiving events from SQS, the NTH can also forward the events to the specified webhook URLs.

This can potentially benefit us in a few ways, e.g.:

- Proactively spinning up a new instance without waiting for the old one to be terminated, whenever a termination event is received. This would shorten the rotation time even further.

- Sending Slack notifications to Coban engineers to keep them informed of any actions taken by the NTH.

We would need to develop and maintain an application that receives webhook events from the NTH and performs the necessary actions.

In addition, we are also rolling out Karpenter to replace the Kubernetes Cluster Autoscaler, as it is able to spin up new instances slightly faster, helping reduce the four minutes delay a Kafka pod remains in Pending state during a node rotation. Incidentally, Karpenter also removes the need for setting up one ASG by AZ, as it is able to deterministically provision instances in a specific AZ, for example where a particular EBS volume resides.

Lastly, to ensure that the performance of our EBS gp3 volumes is both sufficient and cost-efficient, we want to explore autoscaling their throughput and IOPS beyond the baseline, based on the usage metrics collected by our monitoring stack.

References

[1] Dynamic Volume Provisioning | Kubernetes

[2] Troubleshoot EBS volume stuck in Optimizing state during modification | AWS re:Post

We would like to thank our team members and Grab Kubernetes gurus that helped review and improve this blog before publication: Will Ho, Gable Heng, Dewin Goh, Vinnson Lee, Siddharth Pandey, Shi Kai Ng, Quang Minh Tran, Yong Liang Oh, Leon Tay, Tuan Anh Vu.

Join us

Grab is the leading superapp platform in Southeast Asia, providing everyday services that matter to consumers. More than just a ride-hailing and food delivery app, Grab offers a wide range of on-demand services in the region, including mobility, food, package and grocery delivery services, mobile payments, and financial services across 428 cities in eight countries.

Powered by technology and driven by heart, our mission is to drive Southeast Asia forward by creating economic empowerment for everyone. If this mission speaks to you, join our team today!