Engineering

Engineering

Designing Resilient Systems Beyond Retries (Part 1): Rate-Limiting

This post is the first of a three-part series on going beyond retries to improve system resiliency. In this series, we will discuss other techniques and architectures that can be used as part of a strategy to improve resiliency. To start off the series, we will cover rate-limiting.

Software engineers aim for reliability. Systems that have predictable and consistent behaviour in terms of performance and availability. In the electricity industry, reliability may equate to being able to keep the lights on. But just because a system has remained reliable up until a certain point, does not mean that it will continue to be. This is where resiliency comes in: the ability to withstand or recover from problematic conditions or failure. Going back to our electricity analogy - resiliency is the ability to turn the lights back on quickly when say, a natural disaster hits the power grid.

Why We Value Resiliency

Being resilient to many different failures is the best way to ensure a system is reliable and - more importantly - stays that way. At Grab, our architecture features hundreds of microservices, which is constantly stressed in an increasing number of different ways at higher and higher volumes. Failures that would be rare or unusual become more likely as our scale increases. For that reason, we proactively focus on - and require our services to think about - resiliency, even if they have historically been very reliable.

As software systems evolve and become more complex, the number of potential failure modes that software engineers have to account for grows. Fortunately, so do the techniques for dealing with them. The circuit-breaker pattern and retries are two such techniques commonly employed to improve resiliency specifically in the context of distributed systems. In pursuit of reliability, this is a fine start, but it would be wrong to assume that this will keep the service reliable forever. This article will discuss how you can use rate-limiting as part of a strategy to improve resilience, beyond retries.

Challenges with Retries and Circuit Breakers

A common risk when introducing retries in a resiliency strategy is ‘retry storms’. Retries by definition increase the number of requests from the client, especially when the system is experiencing some kind of failure. If the server is not prepared to handle this increase in traffic, and is possibly already struggling to handle the load, it can quickly become overwhelmed. This is counter-productive to introducing retries in the first place!

When using a circuit-breaker in combination with retries, the application has some form of safety net: too many failures and the circuit will open, preventing the retry storms. However, this can be dangerous to rely on. For one thing, it assumes that all clients have the correct circuit-breaker configurations. Knowing how to configure the circuit-breaker correctly is difficult because it requires knowledge of the downstream service’s configurations too.

Introducing Rate-limiting

In a large organisation such as Grab with hundreds of microservices, it becomes increasingly difficult to coordinate and maintain the correct circuit-breaker configurations as the number of services increases.

Secondly, it is never a good idea for the server to depend on its clients for resiliency. The circuit-breaker could fail or simply be bypassed, and the server would have to deal with all requests the client makes.

It is therefore desirable to have some form of rate-limiting/throttling as another line of defence. There are many strategies for rate-limiting to consider.

Types of Thresholds for Rate-limiting

The traditional approach to rate-limiting is to implement a server-side check which monitors the rate of incoming requests and if it exceeds a certain threshold, an error will be returned instead of processing the request. There are many algorithms such as ‘leaky bucket’, fixed/sliding window and so on. A key decision is where to set the thresholds: usually by client, endpoint, or a combination of both.

Rate-limiting by client or user account is the approach taken by many public APIs: Each client is allowed to make a certain number of requests over a period, say 1000 requests per hour, and once that number is exceeded then their requests will be rejected until the time window resets. In this approach, the server must ensure that it has enough capacity (or can scale adequately) to handle the maximum allowed number of requests for each client. If new clients are added frequently, the overhead of maintaining and adjusting the limits may be significant. However, it can be a good way to guarantee a service-level agreement (SLA) with your clients.

An alternative to per-client thresholds is to use per-endpoint thresholds. This limit is applied across all clients and can be set according to the server’s true capacity using benchmarks. Compared with per-client limits this is easier to configure and more reliable in preventing the server from becoming overloaded. However, one misbehaving client may be able to consume the entire quota, blocking other clients of the service.

A rate-limiting strategy may use different levels of thresholds, and this is the best approach to get the benefits of both per-client and per-endpoint thresholds. For example, the following rules might be applied (in order):

- Per-client, per-endpoint: For example, client A accessing the sendEmail endpoint. It is not necessary to configure thresholds at this granularity, but may be useful for critical endpoints.

- Per-client: In addition to any per-client per-endpoint settings, client A could have a global threshold of 1000 requests/hour to any API.

- Per-endpoint: This is the server’s catch-all guard to guarantee that none of its endpoints become overloaded. If client limits are properly configured, this limit should never be reached.

- Server-wide: Finally, a limit on the number of requests a server can handle in total. This is important because even if endpoints can meet their limits individually, they are never completely isolated: the server will have some overhead and limited resources for processing any kind of request, opening and closing network connections etc.

Local vs Global Rate-limiting

Another consideration is local vs global rate-limiting. As we saw in the previous section, backend servers are usually pooled together for resiliency. A naive rate-limiting solution might be implemented at the individual server instance level. This sounds intuitive because the thresholds can be calculated exactly according to the instance’s computing power, and it scales automatically as the number of instances increases. However, in a microservice architecture, this is rarely correct as the bottlenecks are unlikely to be so closely tied to individual instance hardware.

More often, the capacity is reached when a downstream resource is exhausted, such as a database, a third-party service or another microservice. If the rate-limiting is only enforced at the instance level, when the service scales, the pressure on these resources will increase and quickly overload them. Local rate-limiting’s effectiveness is limited.

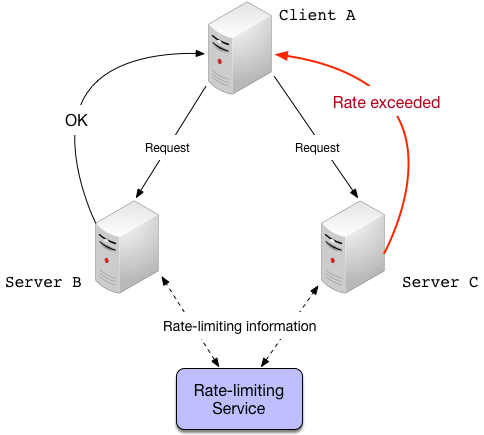

Global rate-limiting on the other hand monitors thresholds and enforces limits across the entire backend server pool. This is usually achieved through the use of a centralised rate-limiting service to make the decisions about whether or not requests should be allowed to go through. While this is much more desirable, implementing such a service is not without challenges.

Considerations When Implementing Rate-limiting

Care must be taken to ensure the rate-limiting service does not become a single point of failure. The system should still function when the rate-limiter itself is experiencing problems (perhaps by falling back to a local limiter). Since the rate-limiter must be in the request path, it should not add significant latency because any latency would be multiplied across every endpoint being monitored. Grab’s own Quotas service is an example of a global rate-limiter which addresses these concerns.

Global rate-limiting with a central server. The servers send information about the request volumes, and the rate-limiting service responds with the rate-limiting decisions. This is done asynchronously to avoid introducing a point of failure.

Global rate-limiting with a central server. The servers send information about the request volumes, and the rate-limiting service responds with the rate-limiting decisions. This is done asynchronously to avoid introducing a point of failure.

Generally, it is more important to implement rate-limiting at the server side. This is because, once again, assuming that clients have correct implementation and configurations is risky. However, there is a case to be made for rate-limiting on the client as well, especially if the clients can be trusted or share a common SDK.

With server-side limiting, the server still has to accept the initial connection, process the rate-limiting logic and return an appropriate error response. With sufficient load, this overhead can be enough to render the system unresponsive; an unintentional denial-of-service (DoS) effect.

Client-side limiting can be implemented by using a central service as described above or, more commonly, utilising response headers from the server. In this approach, the server response may include information about the client’s remaining quota and/or a timestamp at which the quota is reset. If the client implements logic for these headers, it can avoid sending requests at all if it knows they will be rate-limited. The disadvantage of this is that the client-side logic becomes more complex and another possible source of bugs, so this cost has to be considered against the simpler server-only method.

Up Next, Bulkheading, Load Balancing, and Fallbacks…

So we’ve taken a look at rate-limiting as a strategy for having resilient systems. I hope you found this article useful. Comments are always welcome.

In our next post, we will look at the other resiliency techniques such as bulkheading (isolation), load balancing, and fallbacks.

Please stay tuned!